Archive

https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5140-11260467

Archive

Lilliput

- Magazine

- Lilliput

- Stefan Lorant

- 1937

- 1960

43–44 Shoe Lane, Holborn, London EC4.

- English

- London (GB)

The magazine Lilliput, founded by the émigré journalist Stefan Lorant in 1937, gave work to emigrated artists and photographers such as Kurt Hutton, Walter Suschitzky, Walter Trier and Edith Tudor-Hart.

Word Count: 29

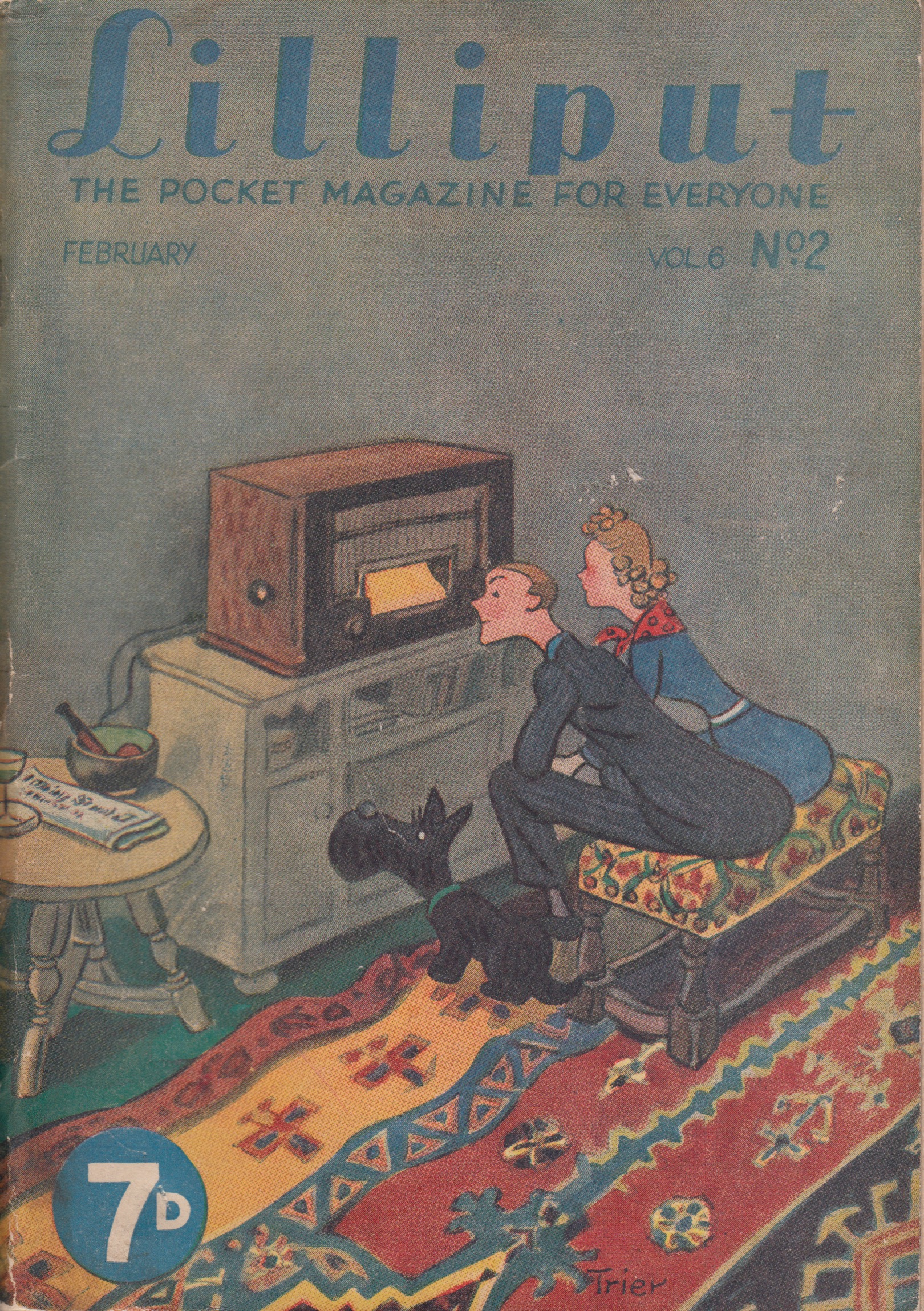

Lilliput, vol. 6, no. 2, 1940, cover by Walter Trier (METROMOD Archive).

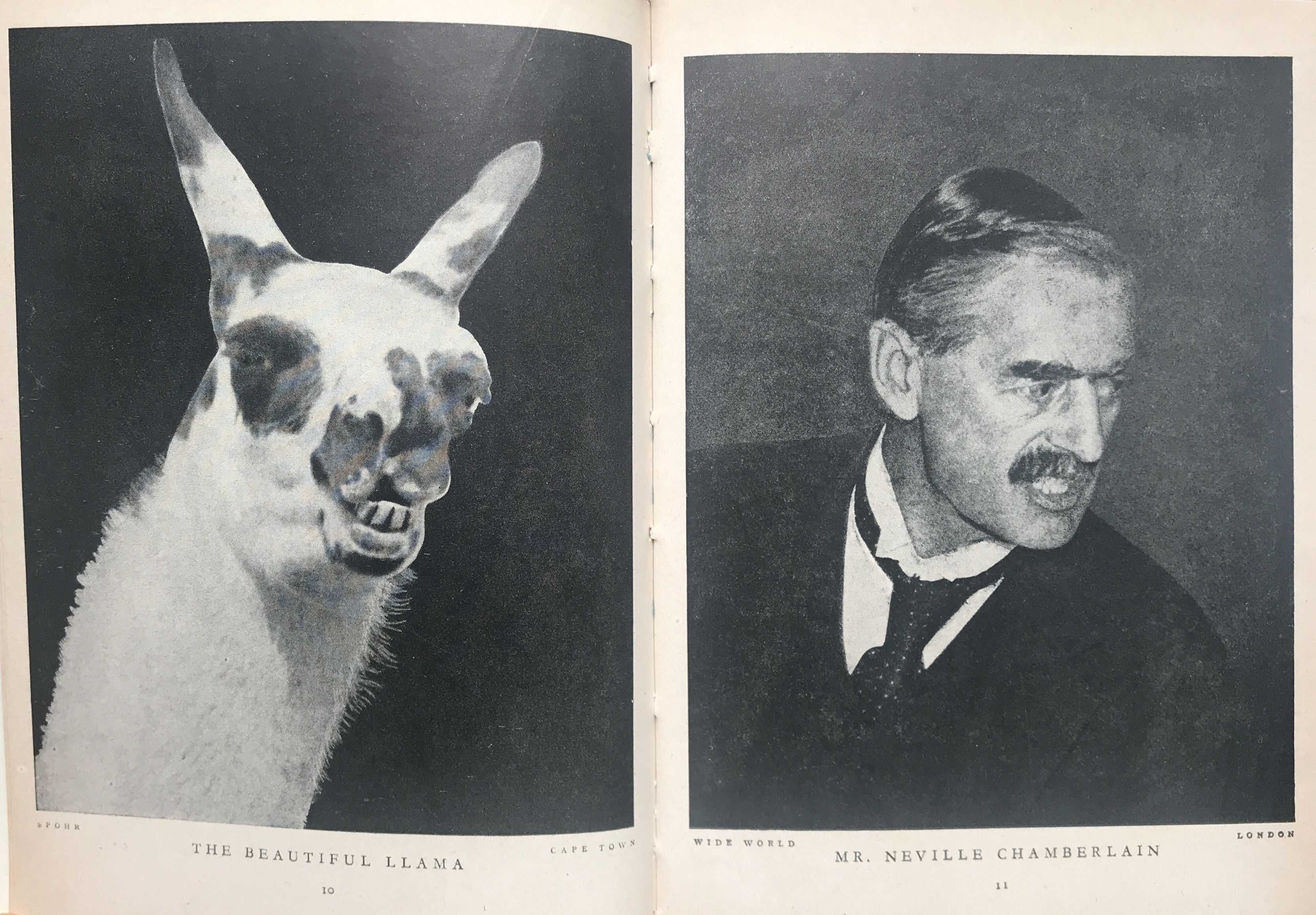

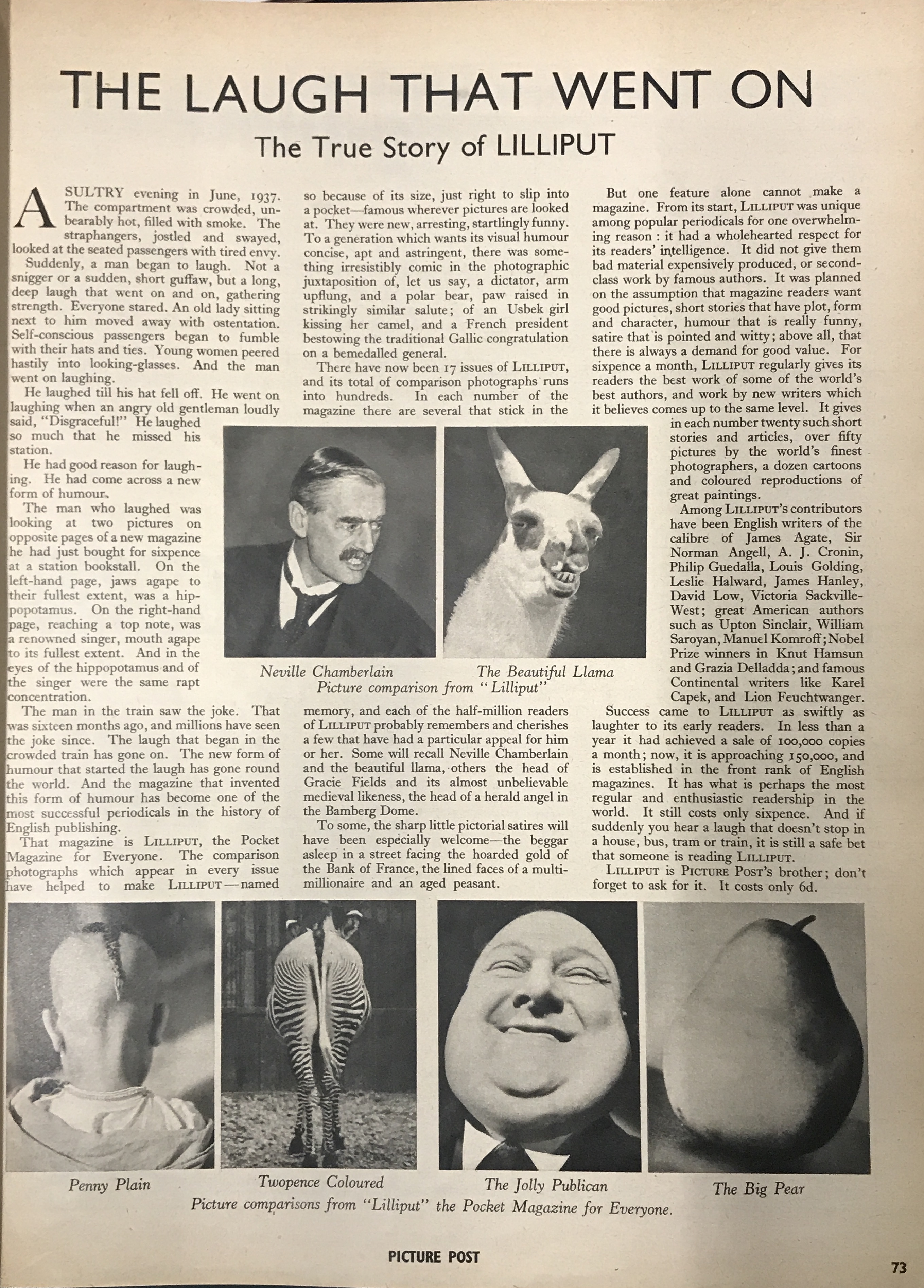

Lilliput, vol. 3, 1938, p. 10: “The Beautiful Llama”, Spohr, Cape Town and p. 11: “Mr. Neville Chamberlain”, photo: “, photo: Wide World, London (Photo: Private Archive).

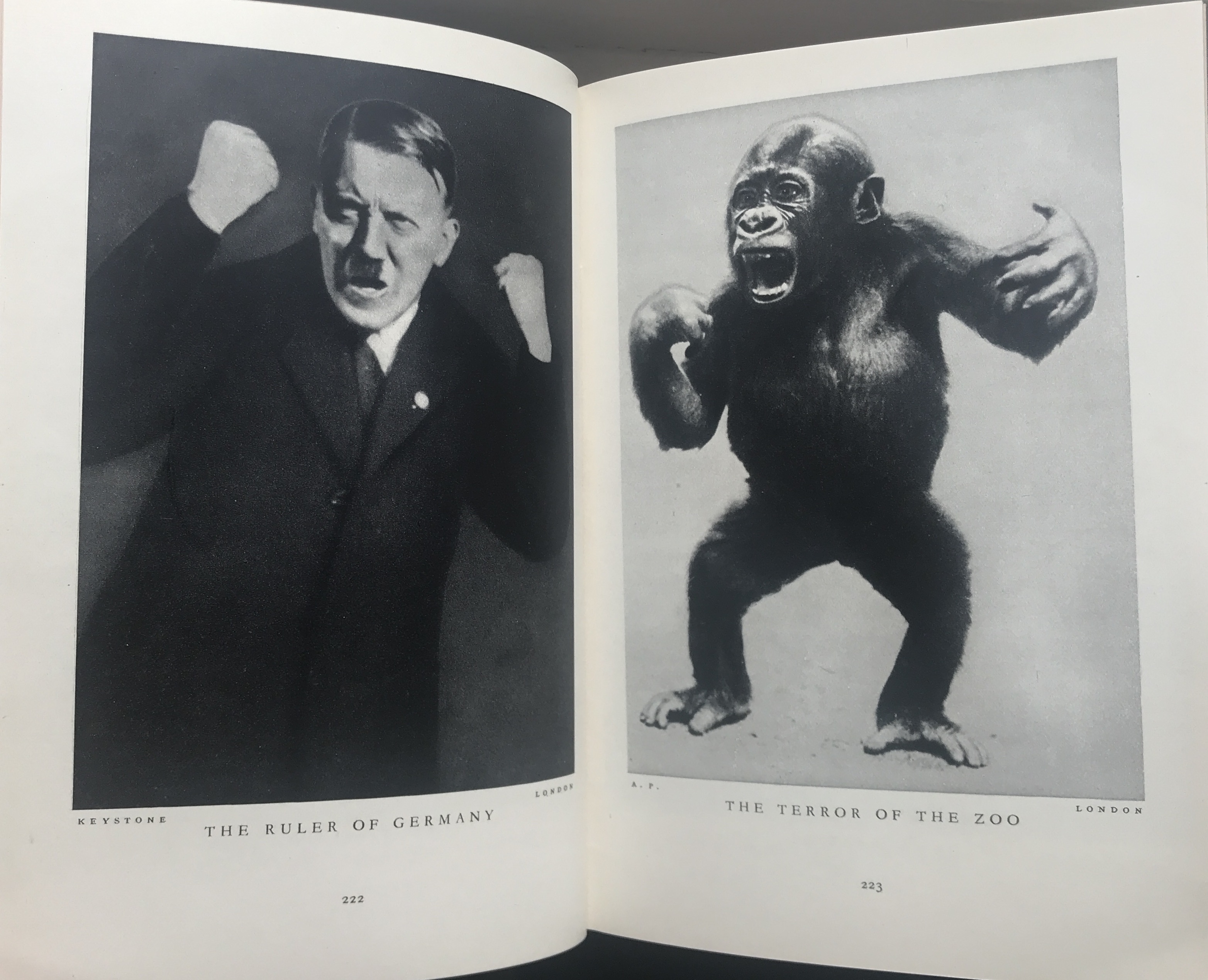

Lilliput, vol. 3, 1938, p. 223: “The Ruler of Germany”, photo: Keystone, London and p. 224: “The Terror of the Zoo”, photo: A. P., London (Photo: Private Archive).

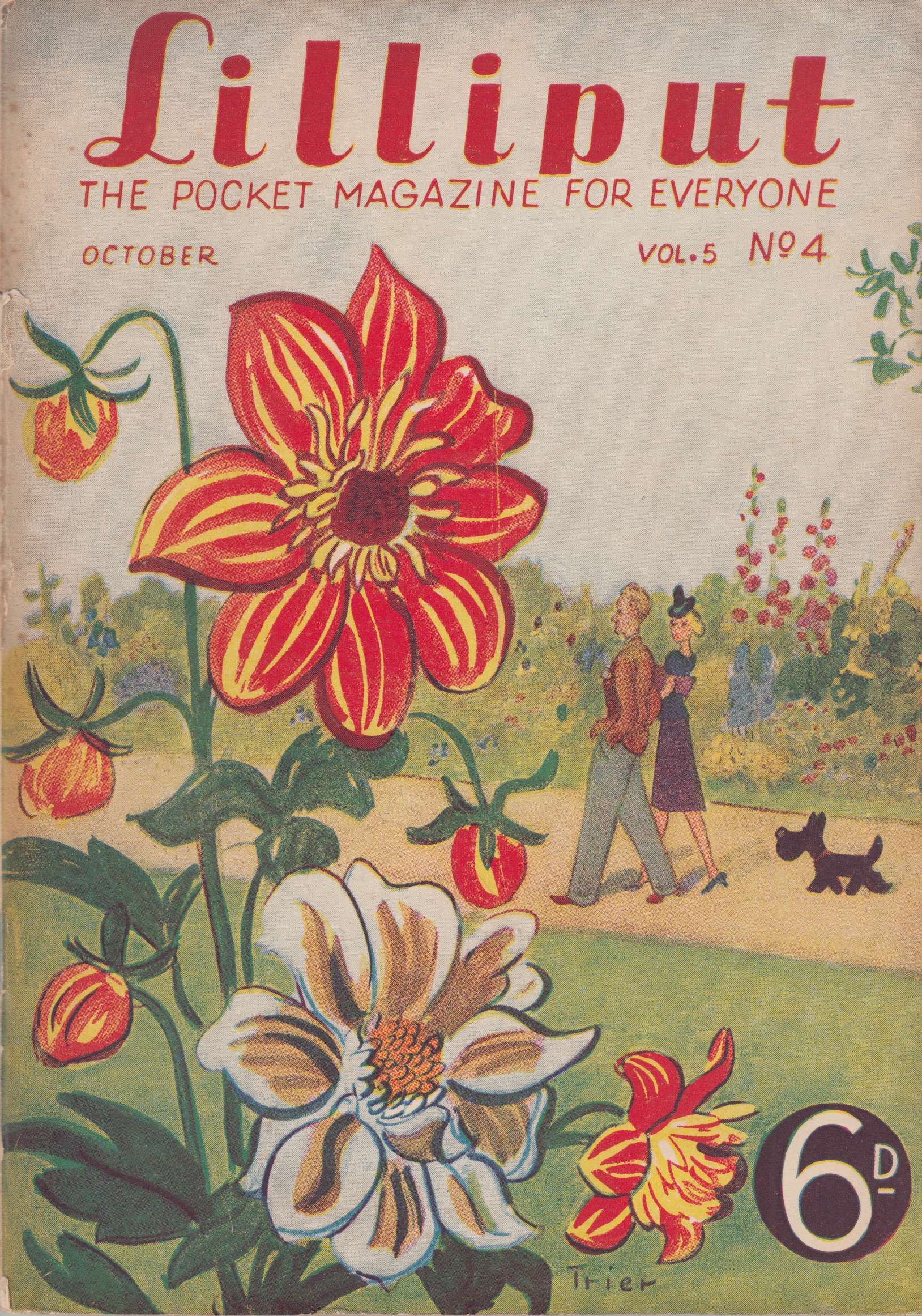

Lilliput, vol. 5, no. 4, 1939, cover by Walter Trier (METROMOD Archive).

Lilliput, vol. 5, no. 4, 1939, contents for October (METROMOD Archive).

Lilliput, vol. 5, no. 4, 1939, p. 322: “We shall conquer the world: German Propaganda Minister, Dr. Goebbels”, photo: Schall, Paris and p. 323: “Goodness! I’m all of a-tremble. Sea-lion in the Zoo”, photo: Keystone, London (METROMOD Archive).

Lilliput, vol. 5, no. 4, 1939, p. 332: drawing by Walter Trier and p. 333: “Sea Spray” by T. Thompson (METROMOD Archive).

Lilliput, vol. 5, no. 4, 1939, p. 411: “Fate in Five Words” by Alfred Polgar (METROMOD Archive). A short story on the homelessness of émigrés.

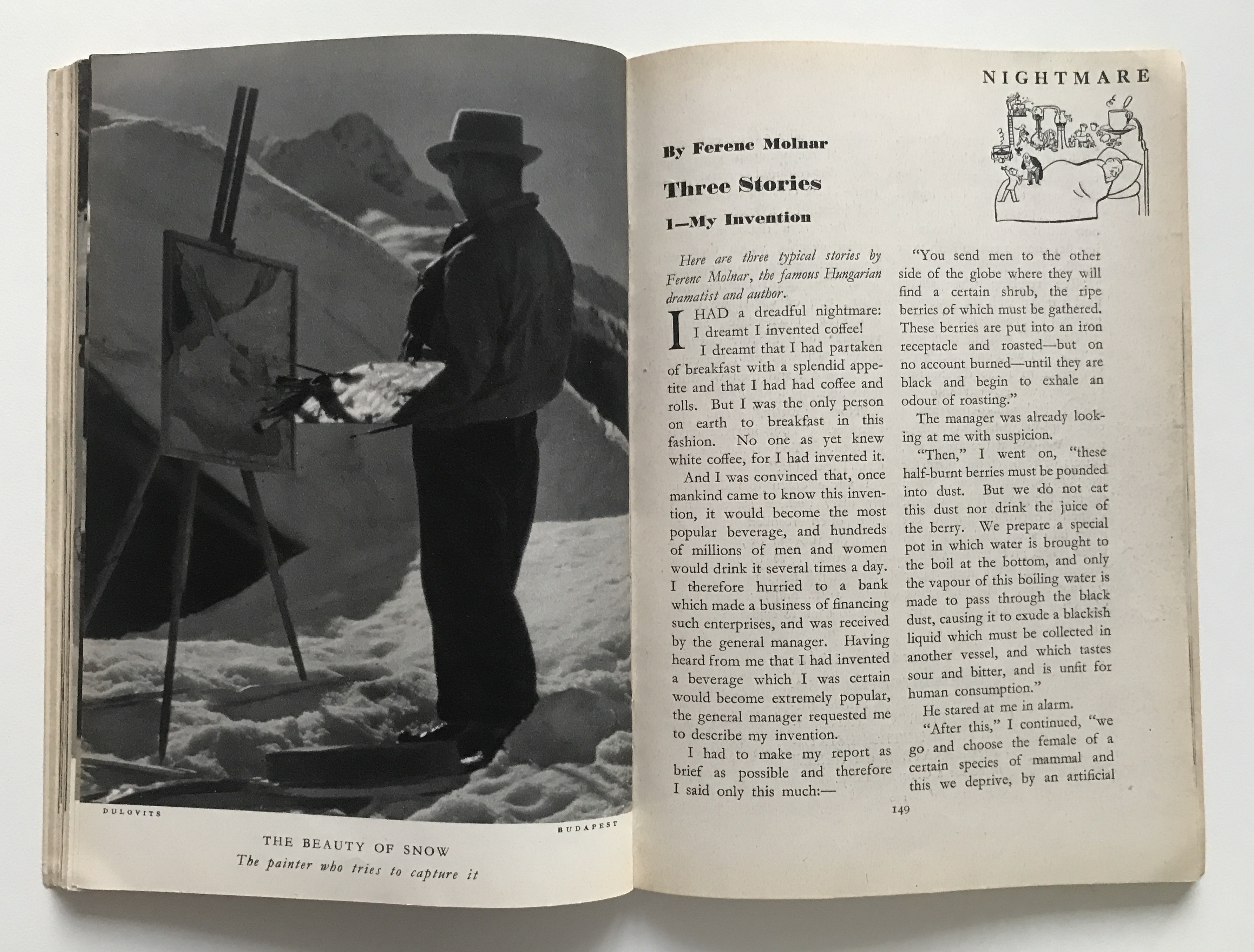

Lilliput, vol. 6, no. 2, 1940, p. 148: “The Beauty of the snow: The painter who tries to capture it”, photo: Dulovits, Budapest and p. 149: “Three Stories” by Ferenc Molnar (METROMOD Archive).

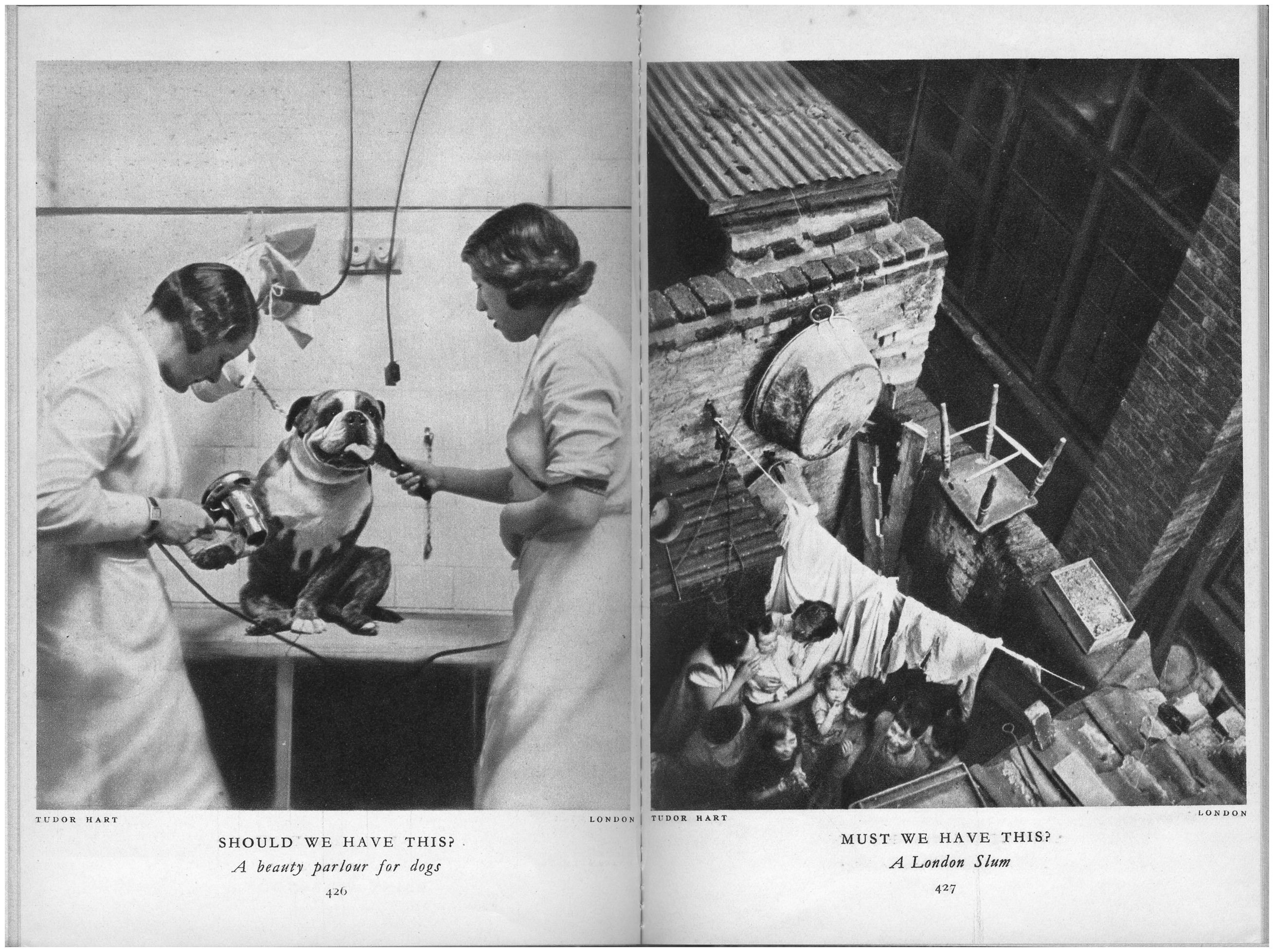

Lilliput, vol. 4, 1939, p. 426: “Should we have this? A beauty parlour for dogs”, photo: Edith Tudor-Hart, c. 1937 and p. 427: “Must we have this? A London slum”, photo: Edith Tudor-Hart, c. 1936 (© The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

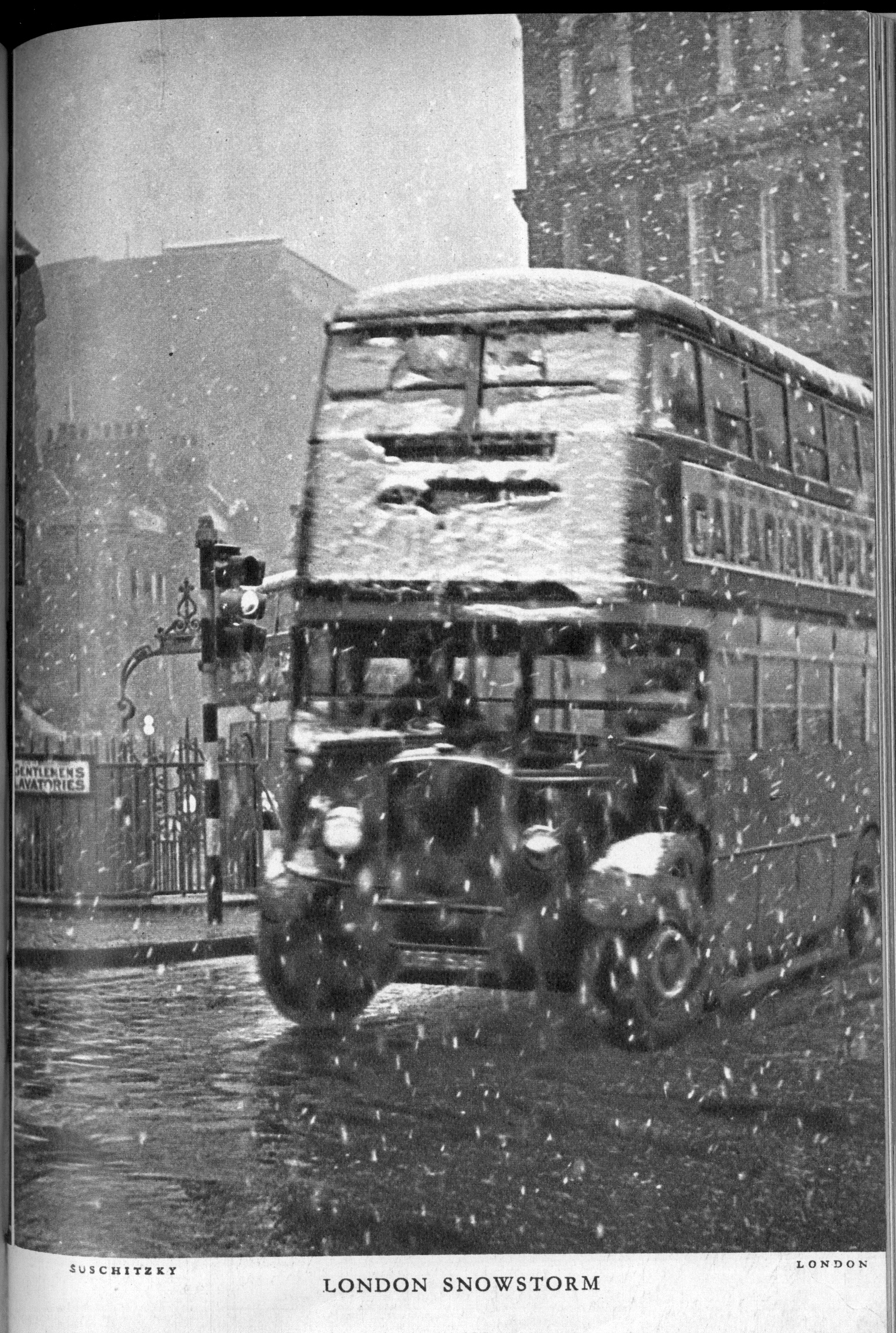

Lilliput, vol. 6, 1940, p. 311: “London Snowstorm”, photo: Wolf Suschitzky (© The Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky).

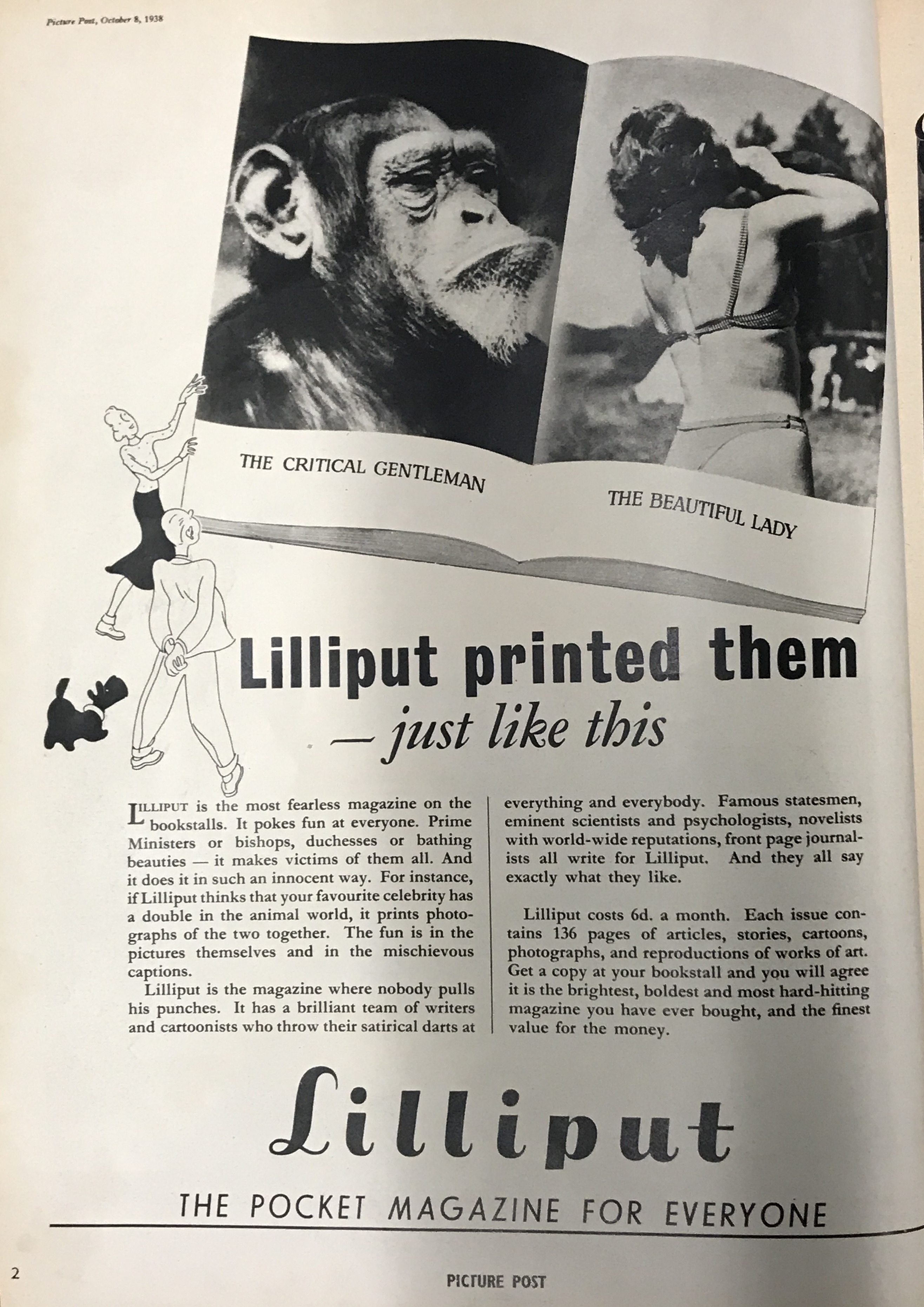

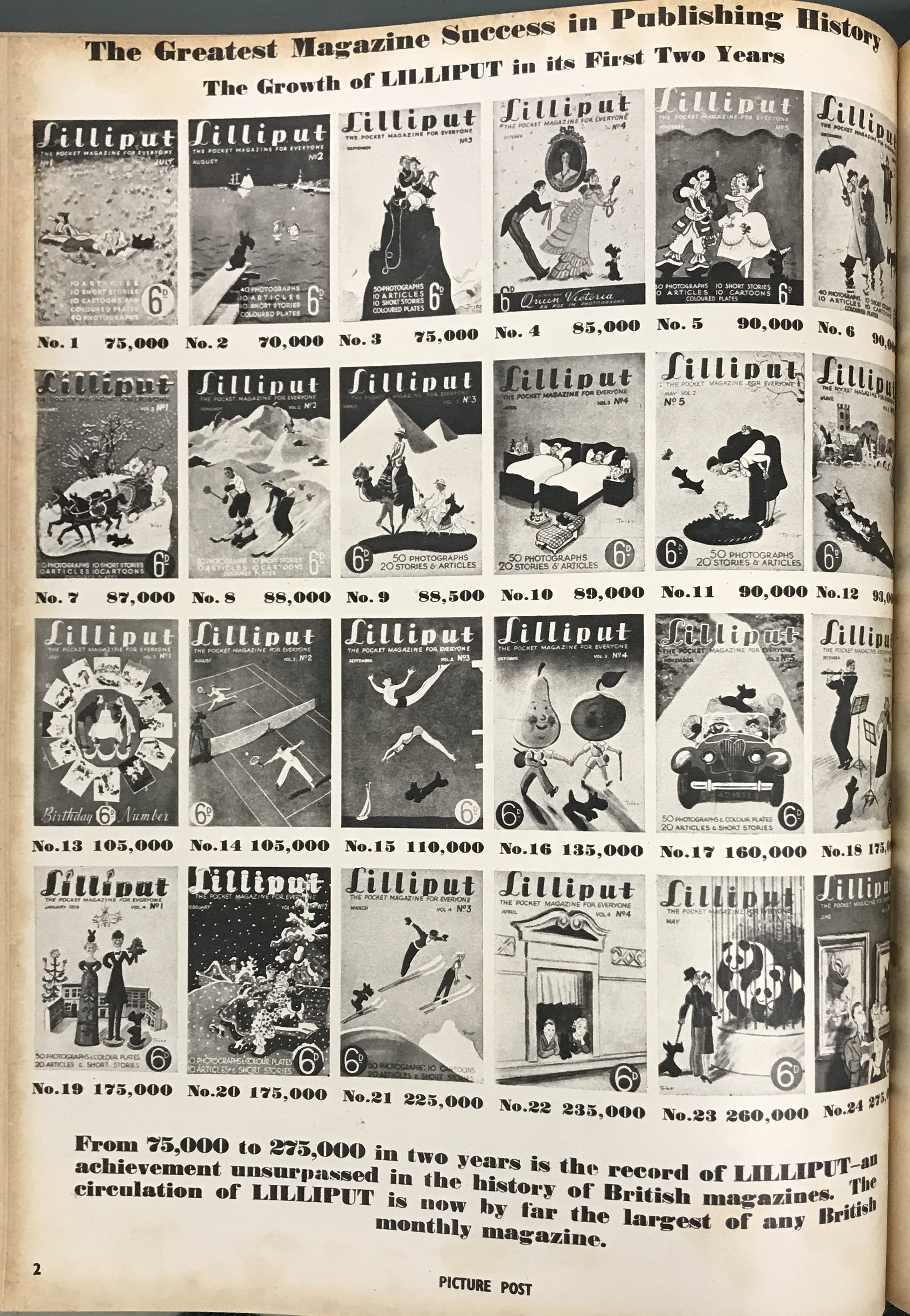

Advertisement for Lilliput in the first issue of Picture Post, vol. 1, 1938, p. 2 (Photo: Private Archive). Both magazines were founded by Stefan Lorant.

Essay on Lilliput in the first issue of Picture Post, vol. 1, 1938, p. 73 (Photo: Private Archive).

Advertisement for Lilliput in Picture Post, vol. 3, 1939, p. 2: overview on Walter Trier’s covers (Photo: Private Archive). Dogramaci, Burcu. “Der Kreis um Stefan Lorant. Von der Münchner Illustrierten Presse zur Picture Post.” Netzwerke des Exils. Künstlerische Verflechtungen, Austausch und Patronage nach 1933, edited by Burcu Dogramaci and Karin Wimmer, Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2011, pp. 163–183.

Dogramaci, Burcu, and Helene Roth. “Fotografie als Mittler im Exil: Fotojournalismus bei Picture Post in London und Fototheorie und -praxis an der New School for Social Research in New York.” Vermittler*innen zwischen den Kulturen, edited by Inge Hansen-Schaberg et al., special issue of Zeitschrift für Museum und Bildung, vol. 86–87, 2019, pp. 13–44.

Hallett, Michael. Stefan Lorant. Godfather of Photojournalism. Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Hopkinson, Amanda. “Picture Post: ‘Strongly political and anti-Fascist’.” Insiders Outsiders. Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Visual Culture, edited by Monica Bohm-Duchen, Lund Humphries, 2019, pp. 121–127.

Lilliput, London, 1937–1960.

Lorant, Stefan. “Introduction.” Idem. Chamberlain and the Beautiful Llama and 101 more juxtapositions. Hulton Press, 1940, pp. 7–13.

Neuner-Warthorst, Antje. Walter Trier. Politik. Kunst. Reklame, edited by Hans Joachim Neyer, exh. cat. Wilhelm-Busch-Museum, Hannover, 2006.

Osman, Colin. “Der Einfluß deutscher Fotografen im Exil auf die britische Pressefotografie.” Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 1986, pp. 83–87.

Picture Post, London, 1938–1957.

Schumann, Klaus. “Der Mann mit den sechs Leben. Die ungewöhnliche Karriere des Stefan Lorant.” Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14/15 December 1985.

Willimowski, Thomas. Stefan Lorant – Eine Karriere im Exil. wvb, 2005.

Word Count: 218

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Lilliput." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5140-11260467, last modified: 12-05-2021.

-

Edith Tudor-HartPhotographerLondon

The Viennese photographer Edith Tudor-Hart emigrated to England in 1933 and made a name with her photographs focusing on questions of class, social exclusion and the lives of marginalised people.

Word Count: 29

John HeartfieldArtistGraphic DesignerFotomonteur (mounter of photographs)LondonAfter escaping from his first exile in Prague in December 1938, the political artist John Heartfield lived in London since 1950, working for Picture Post and the publisher Lindsay Drummond.

Word Count: 28

Wolf SuschitzkyPhotographerCinematographerLondonThe Viennese Wolf Suschitzky made a career as a photographer and cinematographer after emigrating to London in 1935.

Word Count: 17

We make HistoryBookLondonIn 1940, émigré artist Richard Ziegler, using the pseudonym Robert Ziller, published the book We Make History with the Allen & Unwin publishing house in London.

Word Count: 25

“The Life of a Station.”PhotoessayLondonPhotographer Tim N. Gidal’s first reportage for Picture Post magazine after his emigration to London was devoted to Victoria Station, observing travellers and their companions as they depart and arrive.

Word Count: 31

Lighting for Photography. Means and MethodsPhoto guideBookLondonLighting for Photography from 1940 by the émigré photographer Walter Nurnberg was one of a number of successful photo guides produced by Andor Kraszna-Krausz’s Focal Press publishing house.

Word Count: 28

Tim GidalPhotographerPublisherArt HistorianNew YorkTim Gidal was a German-Jewish photographer, publisher and art historian emigrating in 1948 emigrated to New York. Besides his teaching career, he worked as a photojournalist and, along with his wife Sonia Gidal, published youth books.

Word Count: 35

Fritz HenlePhotographerNew YorkFritz Henle was a German Jewish photographer who emigrated in 1936 to New York, where he worked as a photojournalist for various magazines. He also published several photobooks of his travels throughout North America and Asia.

Word Count: 35

Carola GregorPhotographerSculptorNew YorkThe German émigré photographer Carola Gregor was an animal and child photographer and published some of her work in magazines and books. Today her work and life are almost forgotten.

Word Count: 30

Die ZeitungNewspaperLondonFrom 1941 to 1945, the émigré German-language newspaper Die Zeitung was published in London, reporting on the war on the continent and on the situation in Germany.

Word Count: 25