Archive

https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5141-11259338

Archive

Exhibition of German Jewish Artists’ Work: Painting – Sculpture – Architecture

- Exhibition of German Jewish Artists’ Work: Painting – Sculpture – Architecture

Word Count: 9

- Exhibition

- 05-06-1934

- 15-06-1934

The Exhibition of German Jewish Artists’ Work was organised in 1934 by Carl Braunschweig at the Parsons Galleries in Oxford Street and featured 220 works by German Jewish artists.

Word Count: 27

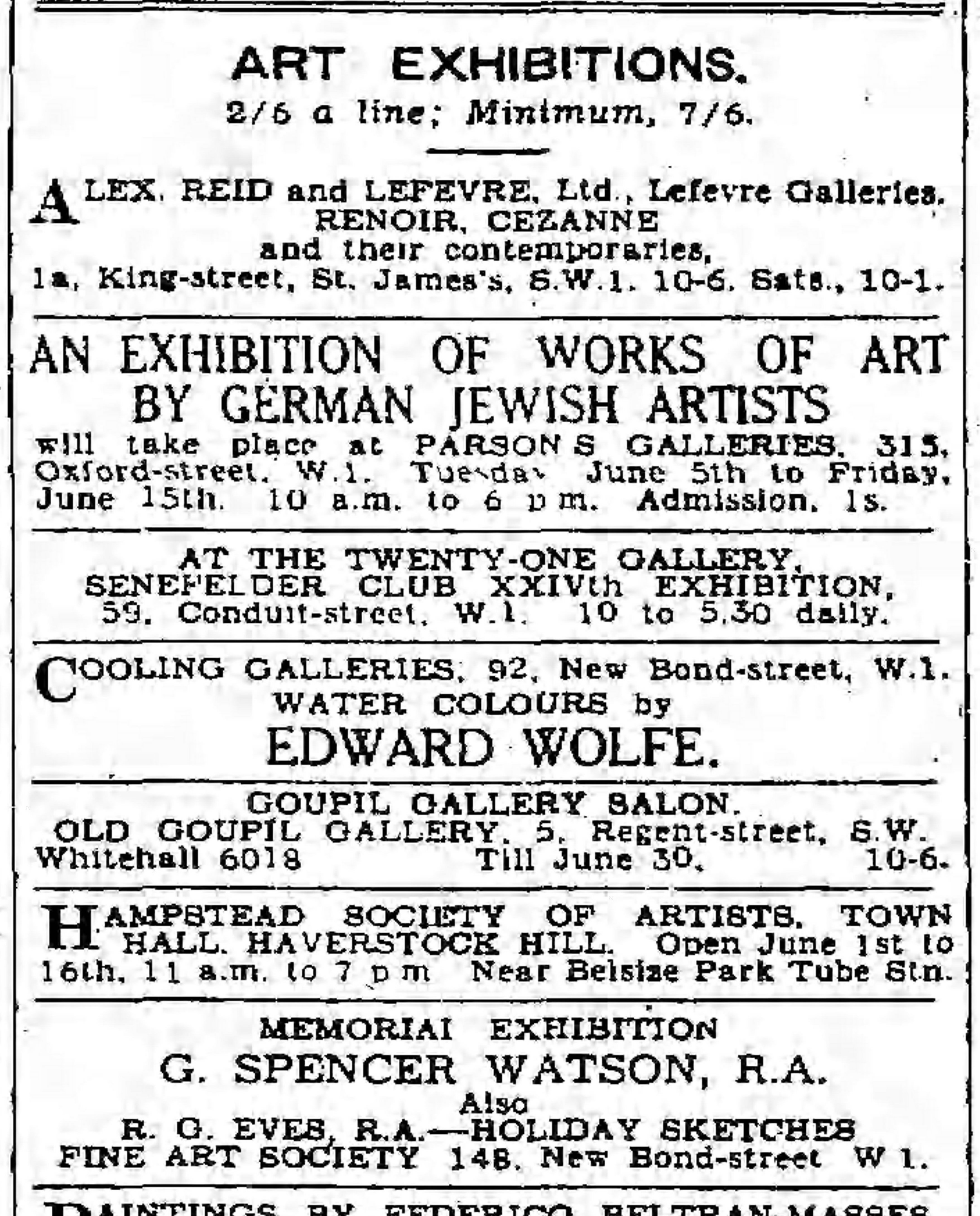

Advertisement “An Exhibition of Works of Art By German Jewish Artists” in The Observer 10 June 1934, p. 14 (Photo: Private Archive).

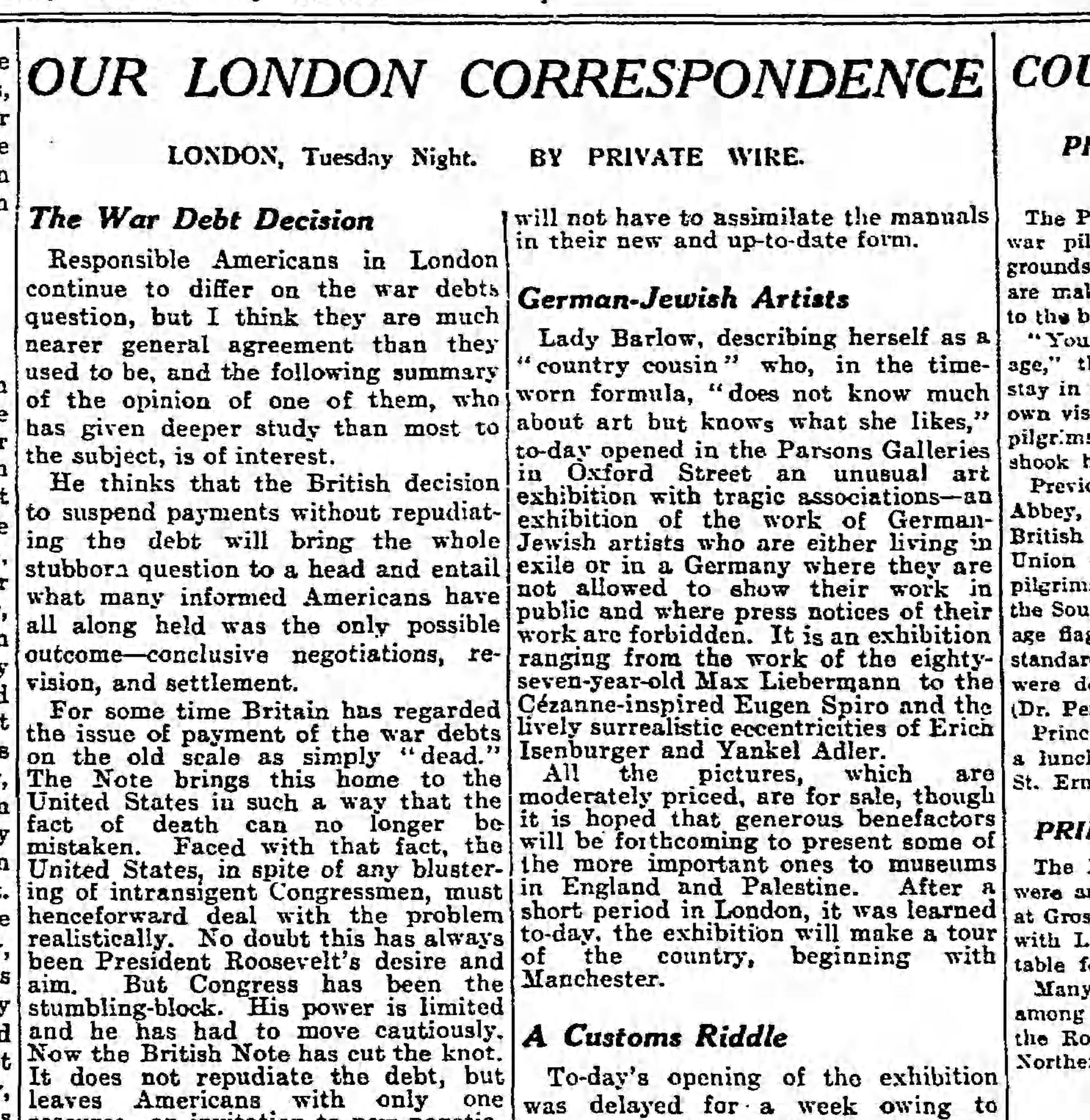

Private Wire. “Our London Correspondence.” The Manchester Guardian, 6 June 1934, p. 10 (Photo: Private Archive). Aronowitz, Richard, and Shauna Isaac. “Émigré Art Dealers and Collectors.” Insiders Outsiders. Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Visual Culture, edited by Monica Bohm-Duchen, Lund Humphries, 2019, pp. 129–135.

Exhibition of German-Jewish Artists’ Work: Painting – Sculpture – Architecture, exh. cat. Parsons Galleries, London, 1934.

Private Wire. “Our London Correspondence.” The Manchester Guardian, 6 June 1934, p. 10.

Summers, Cherith. “Exhibition of German-Jewish Artists’ Work: Painting – Sculpture – Architecture.” Brave New Visions. The Émigrés who transformed the British Art World, exh. cat. Sotheby’s, St. George’s Gallery, London, 2019, p. 14. issuu, https://issuu.com/bravenewvisions/docs/brave_new_visions. Accessed 14 April 2021.

Word Count: 96

This article used transcripts from the exhibition catalogue Exhibition of German-Jewish Artists’ Work exhibition catalogue by Karolina Hyzy and received valuable advice from Rachel Dickson and Sarah MacDougall.

Word Count: 28

Parsons Galleries, 315 Oxford Street, Mayfair, London W1.

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Exhibition of German Jewish Artists’ Work: Painting – Sculpture – Architecture." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5141-11259338, last modified: 09-05-2021.

-

Tommy Apple and his Adventures in Banana-LandBookLondon

The children’s book Tommy Apple and his Adventures in Banana-Land with staged photographs by the émigré Henry Rox shows anthromorphised fruit and vegetables that think, speak and act like humans.

Word Count: 31

20th Century German ArtExhibitionLondonThe 20th Century German Art exhibition of 1938 gave visibility to artists who had been defamed at the Munich exhibition Entartete Kunst and were persecuted by the National Socialist regime.

Word Count: 29

Henry RoxPhotographerSculptorNew YorkHenry Rox was a German émigré sculptor and photographer who, in 1938, arrived in New York with his wife, the journalist and art historian Lotte Rox (née Charlotte Fleck), after an initial exile in London. Besides his work as a sculptor, he began creating humorous anthropomorphised fruit and vegetable photographs.

Word Count: 50

Ludwig Meidner, Drawings 1920–1922 and 1935–49, Else Meidner, Paintings and Drawings 1935–1949ExhibitionLondonIn 1949, a joint exhibition of works by Ludwig and Else Meidner opened at the Ben Uri Art Gallery. It was the first solo exhibition of the artists in London.

Word Count: 29