Archive

Kurt Schwitters

- Kurt

- Schwitters

- 20-06-1887

- Hannover (DE)

- 08-01-1948

- Kendal (GB)

- ArtistPoet

The artist and poet Kurt Schwitters lived in London between 1941 and 1945, where he stood in contact to émigré and local artists, before moving to the Lake District.

Word Count: 27

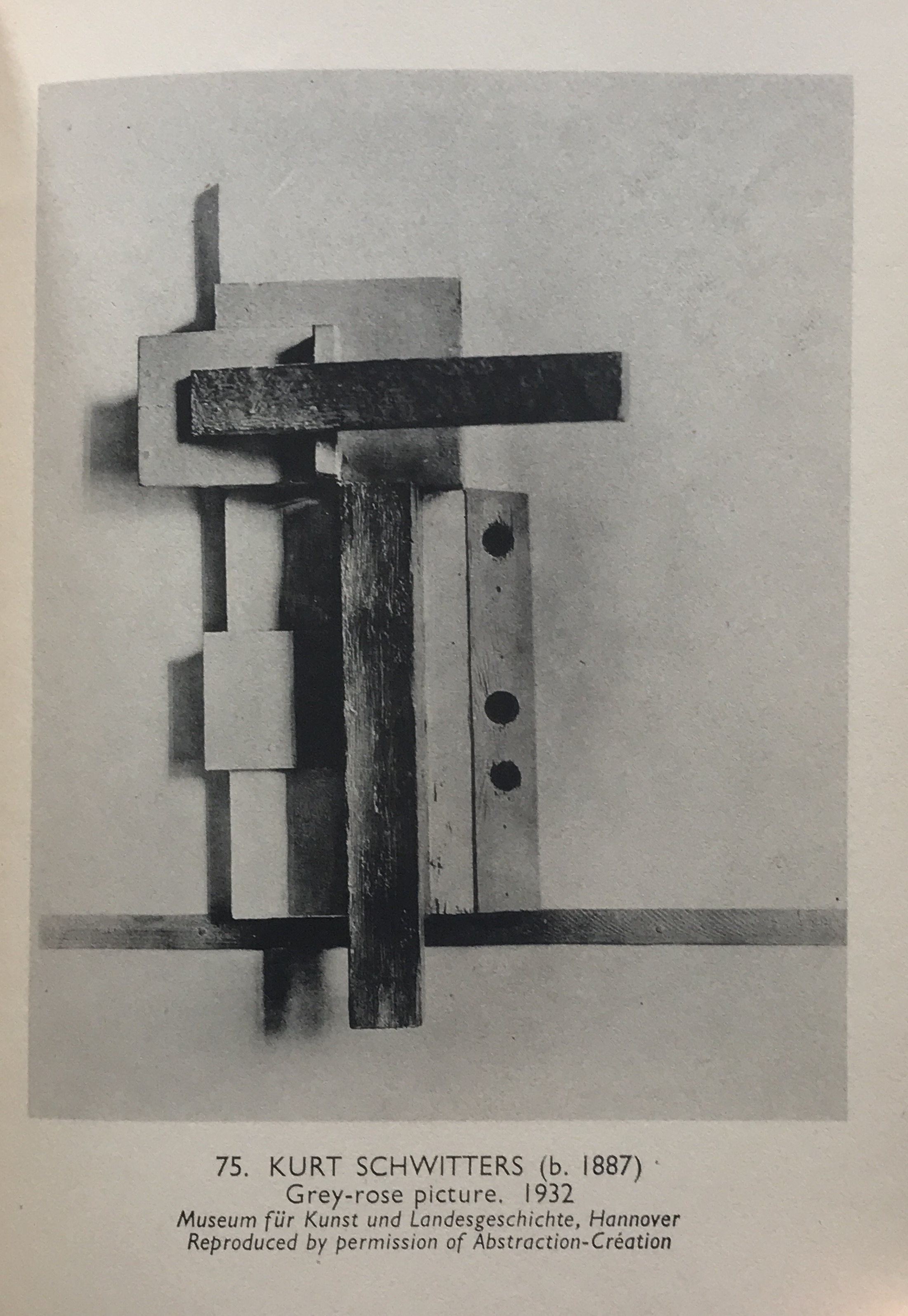

In 1933 Herbert Read reproduced Kurt Schwitters’s Grey-rose picture assemblage (1932) in his book Art Now. An Introduction to the Theory of Modern Painting and Sculpture (METROMOD Archive).

Kurt Schwitters, Red Wire Sculpture, 1944, Metal, plaster, stone, ceramics, dried fruit, wood, painted (Tate Collection, T05767, Photo © Tate, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)).

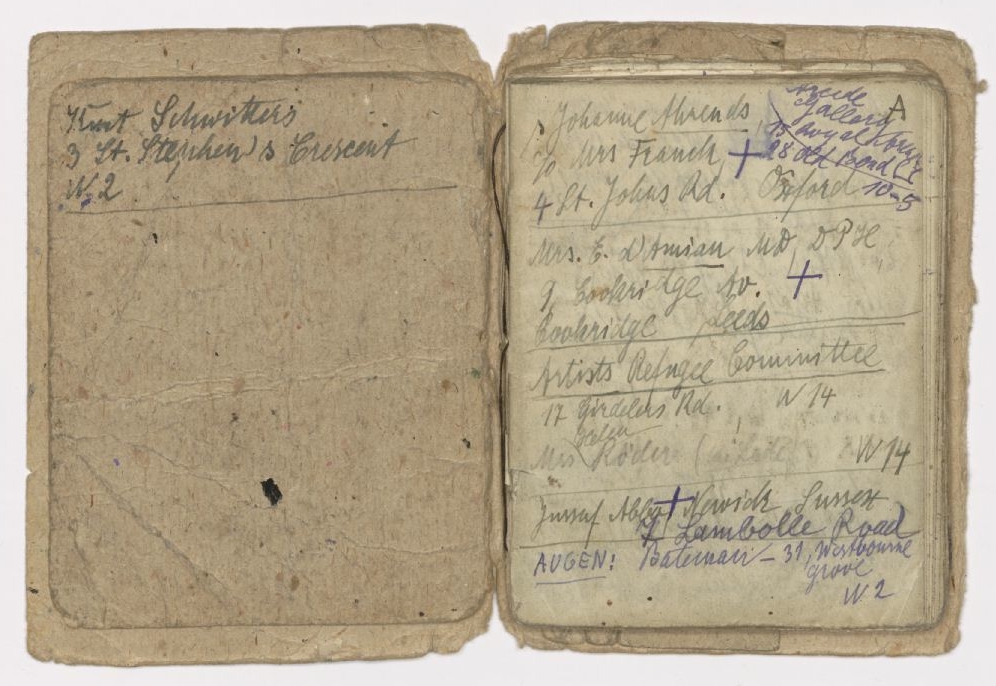

Kurt Schwitters’s London address book, undated [1941/1945] (Sprengel Museum Hannover, Kurt Schwitters Archiv, Hannover, Leihgabe Kurt und Ernst Schwitters Stiftung, Hannover). On the right is the address of Abbo’s studio at Lambolle Road and a reference to the Abbo family in Sussex.

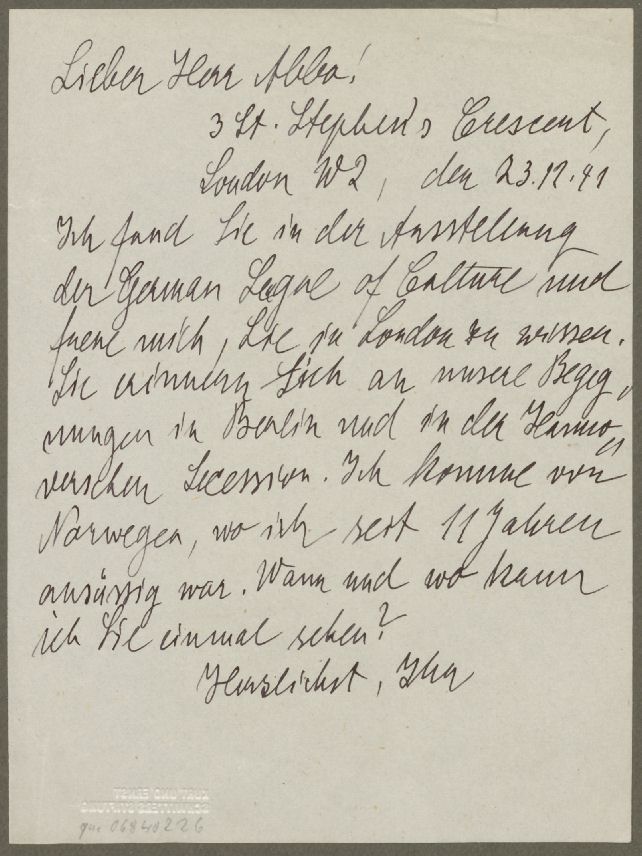

Letter [draft?] from Kurt Schwitters to Jussuf Abbo, London, 23 December 1941 (Sprengel Museum Hannover, Kurt Schwitters Archiv, Hannover, Leihgabe Kurt und Ernst Schwitters Stiftung, Hannover). Schwitters writes: “I found you in the exhibition of the German League of Culture and am glad to have you in London. You remember our meetings in Berlin and at the Hanoversche Secession. I come from Norway, where I have been resident for 11 years. When and where can I see you one day?”

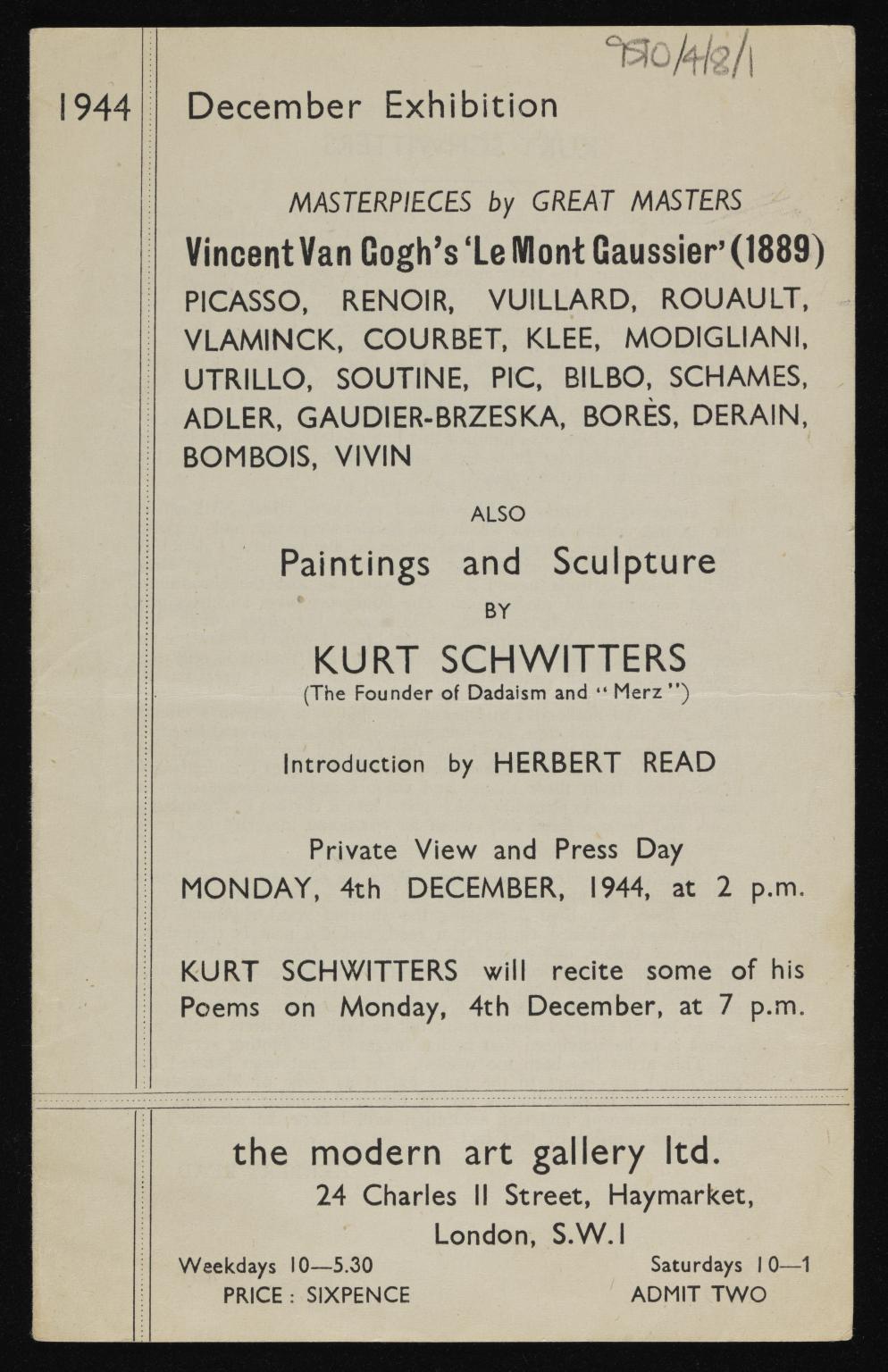

Leaflet advertising the December exhibition held at the Modern Art Gallery on Masterpieces by Great Masters, also featuring Paintings and Sculptures by Kurt Schwitters, Modern Art Gallery Ltd., 1944 (Tate Archive, TGA 9510/4/8/1, Photo © Tate, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)). Chambers, Emma. “Schwitters und England.” Schwitters in England, edited by Emma Chambers and Karin Orchard, exh. cat. Sprengel Museum Hannover, Hannover, 2013, pp. 6–19.

Dickson, Rachel. “‘Our horizon is the barbed wire’: Artistic Life in the British Internment Camps.” Insiders Outsiders. Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Visual Culture, edited by Monica Bohm-Duchen, Lund Humphries, 2019, pp. 147–156.

Erlhoff, Michael, and Klaus Stadtmüller, editors. Kurt Schwitters Almanach, vol. 8. Postskriptum-Verlag, 1989.

Exhibition of 20th century German art, exh. cat. New Burlington Galleries, London, 1938.

Friedenthal, Richard. Die Welt in der Nußschale. Piper, 1956.

Giedion-Welcker, Carola. Schriften 1926–1971. Stationen zu einem Zeitbild, edited by Reinhold Hohl, Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg, 1973.

Müller-Härlin, Anna. “‘Remember Hannover, Berlin, Paris’: Kurt Schwitters’ alte und neue Freunde in London.” Merzgebiete. Kurt Schwitters und seine Freunde, edited by Karin Orchard and Isabel Schulz, exh. cat. Sprengel Museum Hannover, Hannover, 2006, pp. 182–195.

Orchard, Karin. “‘British made’. Die späten Collagen von Kurt Schwitters.” Schwitters in England, edited by Emma Chambers and Karin Orchard, exh. cat. Sprengel Museum Hannover, Hannover, 2013, pp. 56–65.

Pezzini, Barbara. “‘For an appreciation of art and architecture’. The Goldfinger Collection at 2 Willow Road.” Apollo, vol. 153, no. 470, 2001, pp. 55–59.

Powell, Jennifer. “Unter Freunden. Schwitters im Internierungslager.” Schwitters in England, edited by Emma Chambers and Karin Orchard, exh. cat. Sprengel Museum Hannover, Hannover, 2013, pp. 32–35.

Pross, Steffen. “In London treffen wir uns wieder”. Vier Spaziergänge durch ein vergessenes Kapitel deutscher Kulturgeschichte nach 1933. Eichhorn, 2000.

Read, Herbert. Art Now. An Introduction to the Theory of Modern Painting and Sculpture. Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1933.

Schwitters, Kurt. Letter to Jussuf Abbo. Kurt Schwitters Archiv (Sprengel Museum, Hannover, 23 December 1941, London).

Schwitters, Kurt. Wir spielen, bis uns der Tod abholt. Briefe aus fünf Jahrzehnten, edited by Ernst Nündel, Ullstein, 1974.

Vinzent, Jutta. “Muteness as Utterance of a Forced Reality – Jack Bilbo’s Modern Art Gallery (1941–1948).” Arts in Exile in Britain 1933–1945. Politics and Cultural Identity (The Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, 6 (2004)), edited by Shulamith Behr and Marian Malet, Rodopi, 2005, pp. 301–337.

Vinzent, Jutta. Identity and Image. Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933–1945) (Schriften der Guernica-Gesellschaft, 16). VDG, 2006.

Wilson, Sarah. “Kurt Schwitters in England.” 2013, Tate, www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/schwitters-britain/essay-sarah-wilson-kurt-schwitters-england. Accessed 20 February 2021.

Word Count: 362

Sprengel Museum Hannover, Kurt Schwitters Archiv, Hannover.

Tate Collection, London.

Tate Archive, London.

Word Count: 13

My deepest thanks go to Karin Orchard from Sprengel Museum Hannover who provided me with images and permission for Schwitters’s address book and letter. I am grateful to be able to reproduce Schwitters’s work in the Tate Collection under Creative Commons license.

Word Count: 44

Norway (1937–1940); London, GB (1940–1945); Ambleside, Westmoreland, GB (1945–1948).

3 St. Stephen’s Crescent, Bayswater, London W2 (residence, 1941–1942); 39 Westmoreland Road, Barnes, London SW13 (residence, 1942–1945).

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Kurt Schwitters." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5138-11259275, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

László Moholy-NagyPhotographerGraphic DesignerPainterSculptorLondon

László Moholy-Nagy emigrated to London in 1935, where he worked in close contact with the local avantgarde and was commissioned for window display decoration, photo books, advertising and film work.

Word Count: 30

Jussuf AbboSculptorGraphic ArtistLondonThe Berlin sculptor Jussuf Abbo emigrated together with his family to London in 1935, where he received a limited number of commissions and participated in a few group exhibitions.

Word Count: 28

Herbert ReadArt HistorianArt CriticPoetLondonThe British art historian Herbert Read established himself as a central figure in the London artistic scene in the 1930s and was one of the outstanding supporters of exiled artists.

Word Count: 30

Freie Deutsche KulturNewsletterLondonThe Free German League of Culture was an association of emigrant artists and authors who organised exhibitions, concerts and lectures. The events were announced in the Freie Deutsche Kultur newsletter.

Word Count: 30

Aid to RussiaExhibitionLondonThe Aid to Russia exhibition was organised in 1942 by the emigré architect Ernö Goldfinger and his wife, the painter Ursula Goldfinger, at their house in Hampstead.

Word Count: 26

20th Century German ArtExhibitionLondonThe 20th Century German Art exhibition of 1938 gave visibility to artists who had been defamed at the Munich exhibition Entartete Kunst and were persecuted by the National Socialist regime.

Word Count: 29

Ludwig Meidner, Drawings 1920–1922 and 1935–49, Else Meidner, Paintings and Drawings 1935–1949ExhibitionLondonIn 1949, a joint exhibition of works by Ludwig and Else Meidner opened at the Ben Uri Art Gallery. It was the first solo exhibition of the artists in London.

Word Count: 29

Modern Art GalleryArt GalleryLondonThe Modern Art Gallery, founded by the émigré painter, sculptor and writer Jack Bilbo, was a forum for the presentation of modern art, specialising in the work of emigrant artists.

Word Count: 30

Faber & FaberPublishing HouseLondonFaber & Faber shows the importance of publishing houses as supporters of contemporary art movements and of the contribution of emigrants, helping to popularise their art and artistic theories.

Word Count: 29

Marlborough Fine ArtArt GalleryLondonMarlborough Fine Art was founded in 1946 by the Viennese emigrants Harry Fischer and Frank Lloyd in the Mayfair district, focused on Impressionists, Modern and Contemporary Art.

Word Count: 26