Archive

Jussuf Abbo

- Jussuf

- Abbo

Joseph M. Abbo

- 1890

- Ẕefat (IL)

- 29-08-1953

- London (GB)

- SculptorGraphic Artist

The Berlin sculptor Jussuf Abbo emigrated together with his family to London in 1935, where he received a limited number of commissions and participated in a few group exhibitions.

Word Count: 28

Jussuf Abbo, Selbstbildnis, in Der Querschnitt, vol. 4, no. 1, 1924, p. 71 (Photo: Private Archive, © Estate of Jussuf Abbo).

Else Lasker-Schüler, “Jussuff Abbu.” Berliner Börsen-Courier, vol. 55, no. 327, 15 July 1923, p. 5 (Photo: Private Archive).

Jussuf Abbo, Untitled [Else Lasker Schüler?], n.d. [1920s], lithograph, 52 x 39,5 cm (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2010, © Estate of Jussuf Abbo).

Genja Jonas, Portrait Jussuf Abbo, 1926 (© Estate of Jussuf Abbo).

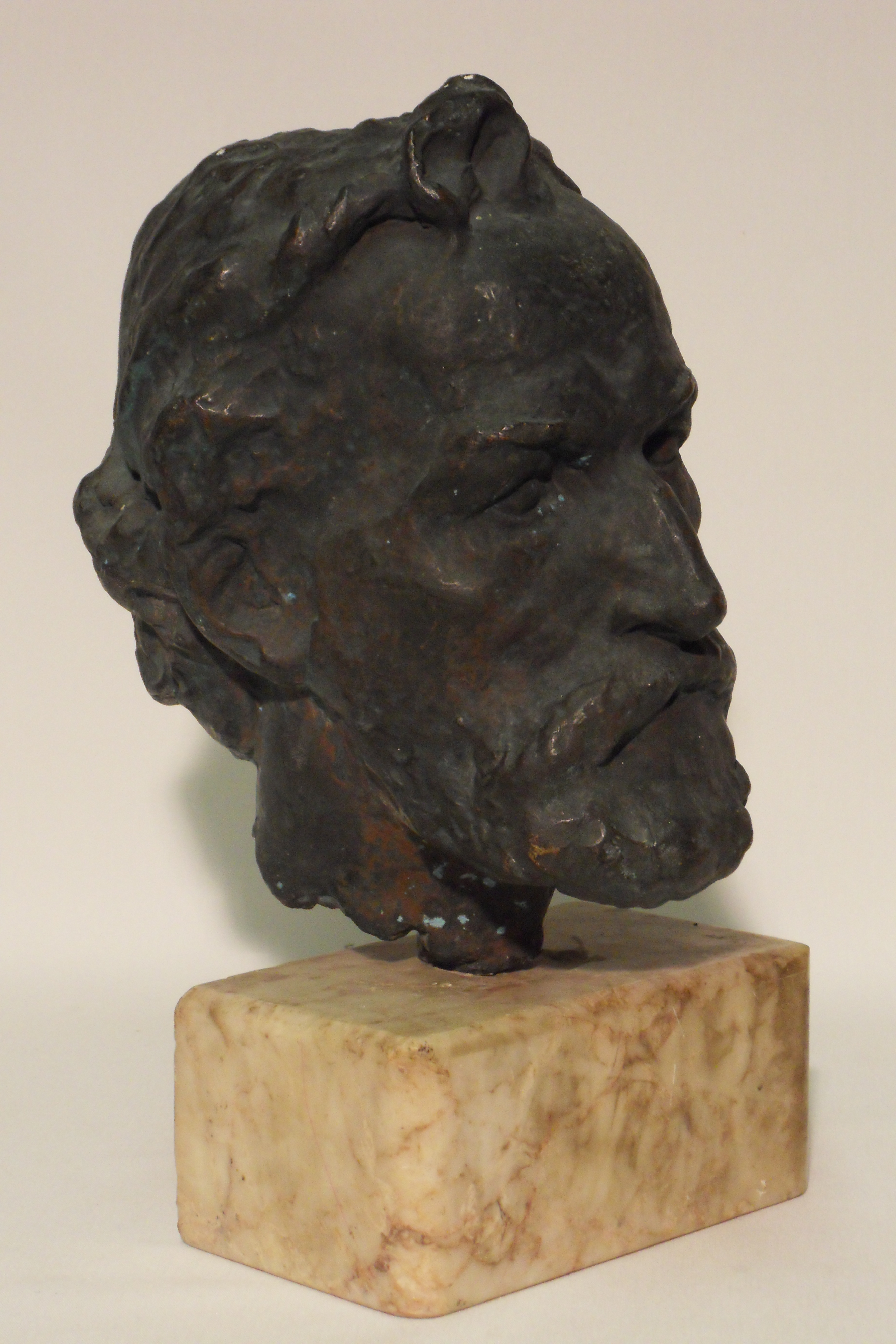

Jussuf Abbo, Untitled [Thomas Sturge Moore?], n.d. [1940], bronze, H. 27 cm (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2010, © Estate of Jussuf Abbo).

Jussuf Abo, Untitled, 1928, plaster, 36 x 29 x 22 cm (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2010, © Estate of Jussuf Abbo).

Jussuf Abo, Untitled, n.d., clay, coloured, 37,5 x 18 cm (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2010, © Estate of Jussuf Abbo).

Jussuf Abbo, Untitled [sleeping girl], n.d. [c. 1939/40], clay (© Estate of Jussuf Abbo).

Jussuf Abbo, Untitled [c. 1939/40], n.d., clay, 15 x 36 cm (© Estate of Jussuf Abbo).

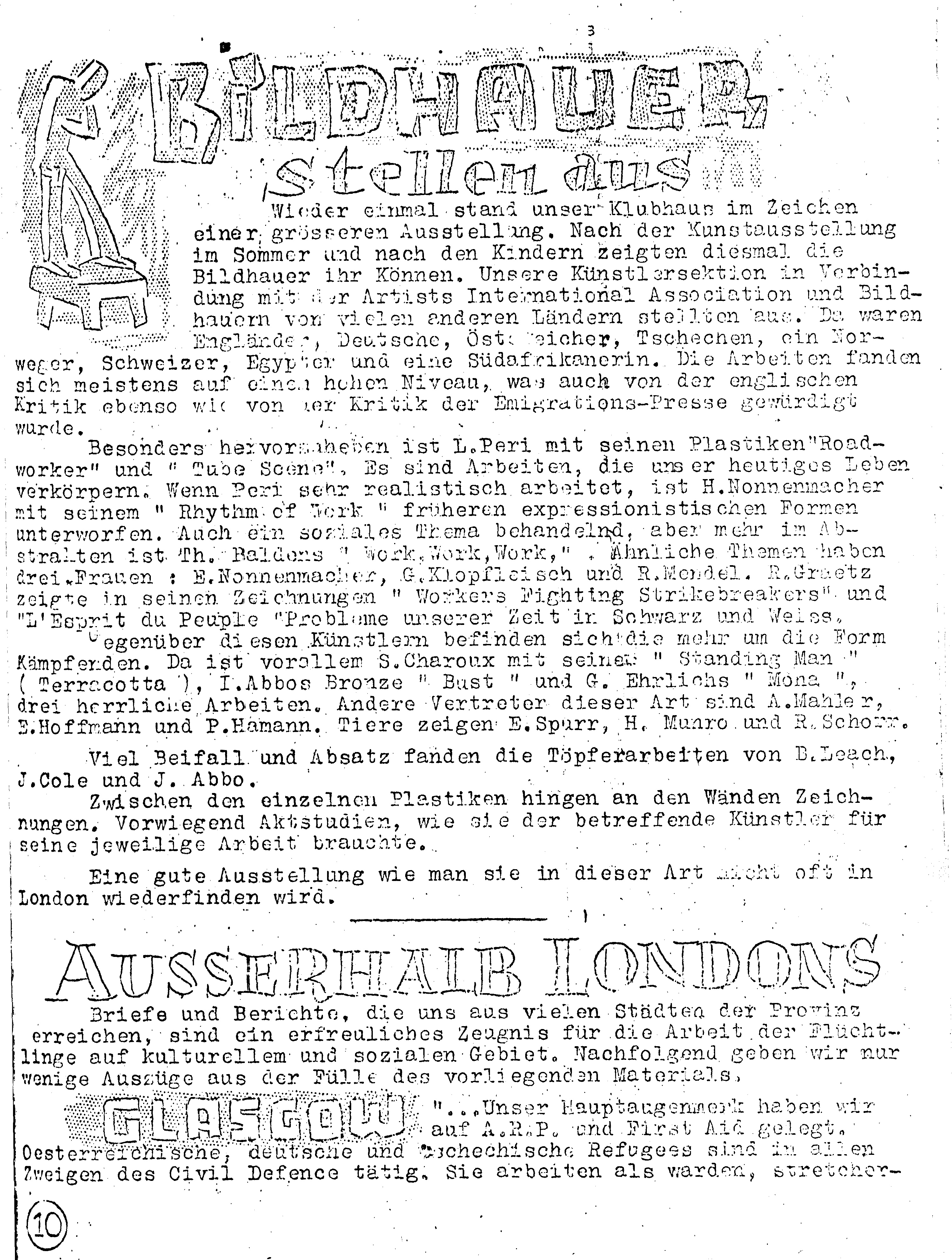

Review of the Exhibition of Sculpture, Pottery and Sculptors’ Drawings in the monthly newsletter Freie Deutsche Kultur (no. 12, 1941, p. 10). The exhibition was organised by the Free German League of Culture and the Artists International Association. Abbo is mentioned twice with reference to a bronze bust and potteries (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

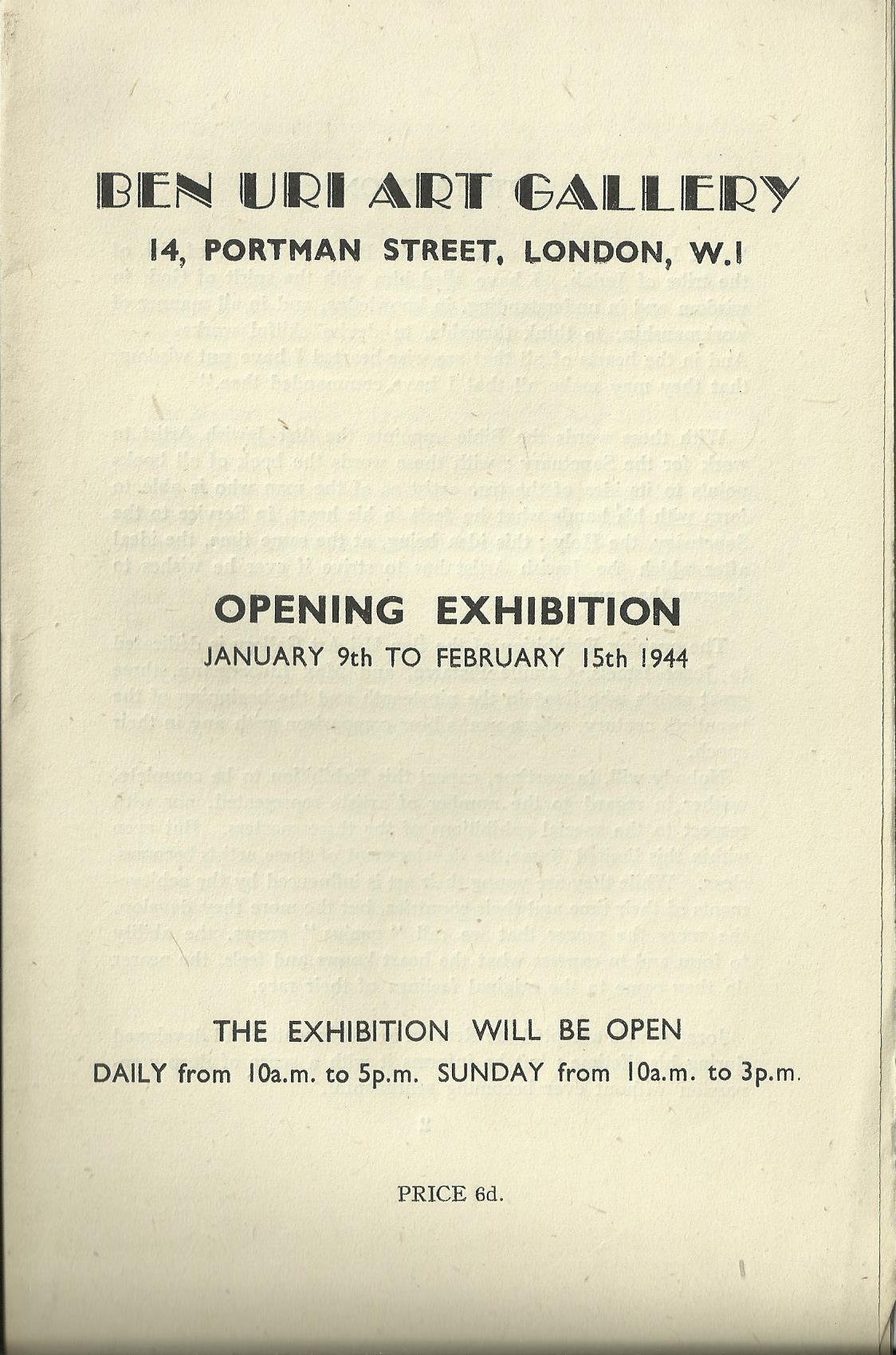

Jussuf Abbo took part in the Opening Exhibition at Ben Uri Art Gallery in 1944 (© Ben Uri Archive).

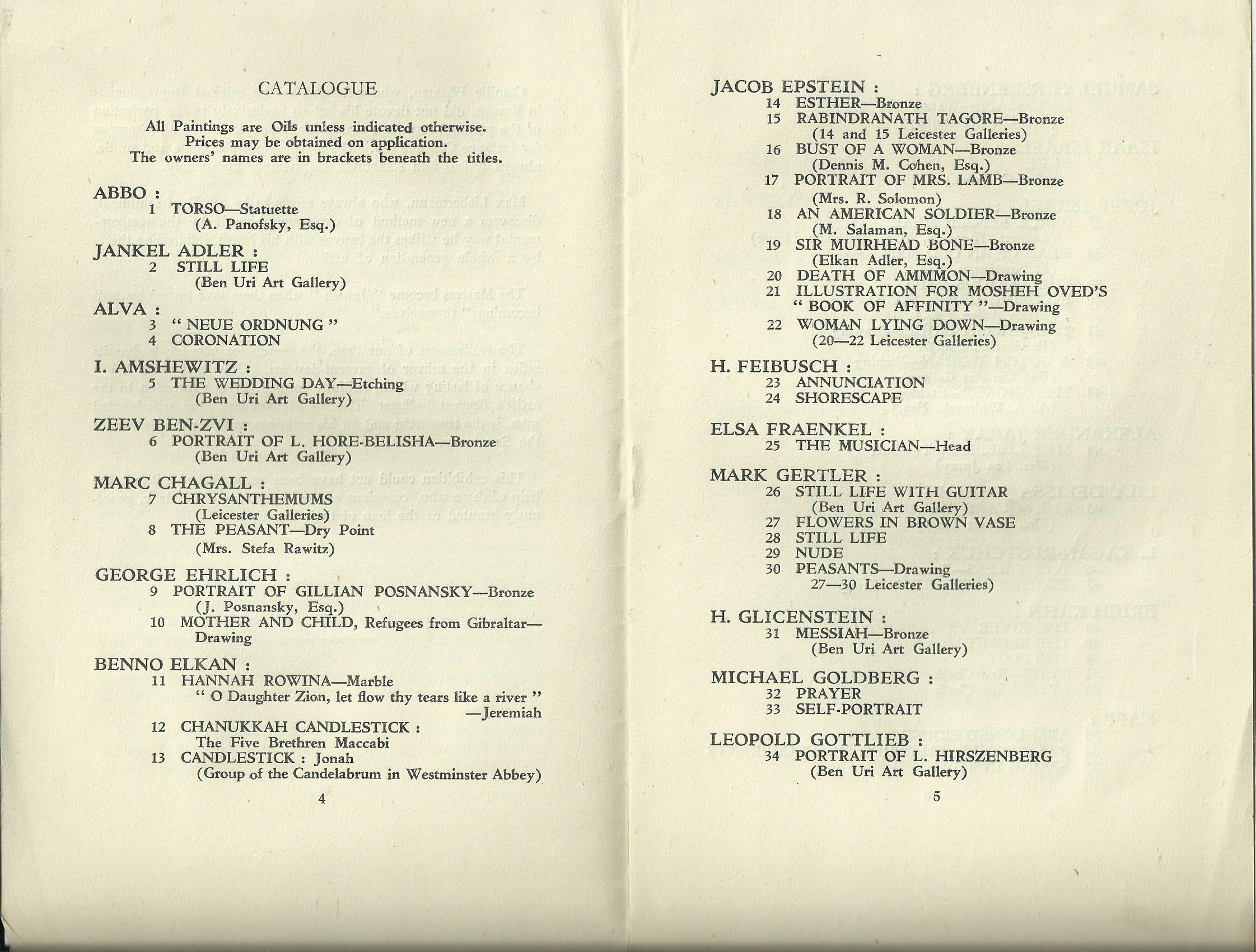

Opening Exhibition, exh cat. Ben Uri Gallery, London, 1944, p. 4–5 with Abbo’s Torso listed as first entry (© Ben Uri Archive).

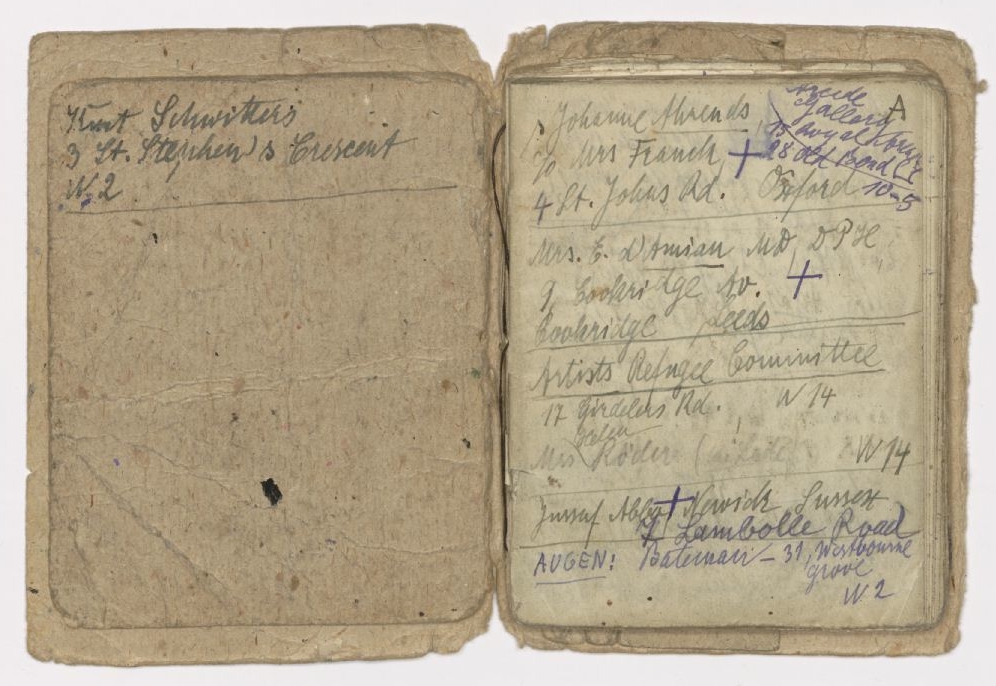

Kurt Schwitters’s London address book, undated [1941/1945] (Sprengel Museum Hannover, Kurt Schwitters Archiv, Hannover, Leihgabe Kurt und Ernst Schwitters Stiftung, Hannover). On the right is the address of Abbo’s studio at Lambolle Road and a reference to the Abbo family in Sussex. Abbo, Ruth. Handschriftliches Manuskript (Estate of Jussuf Abbo, Brighton, 26 September 1957).

Abbo, Ruth. “Über den Verlust einer Existenz. Jussuf Abbo im Exil.” Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 1986, pp. 181–184.

Anonymous. “Bildhauer stellen aus.” Freie Deutsche Kultur, no. 12, 1941, p. 10.

Dickson, Rachel. “Emigré Artists and the Ben Uri.” Forced Journeys. Artists in Exile in Britain c. 1933–45, edited by Rachel Dickson and Sarah MacDougall, exh. cat. Ben Uri Gallery. The London Jewish Museum of Art, London, 2009, pp. 86–90.

Dogramaci, Burcu. Deutschland, fremde Heimat. Zur Rückkehr emigrierter Bildhauer nach 1945 = Germany, a Foreign Land. The Return of Émigré Sculptors after 1945 (Schriftenreihe des Kunsthauses Dahlem). Kunsthaus Dahlem, 2015.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Jussufs Gedicht für Jussuf Abbo.” Der Blaue Reiter ist gefallen. Else Lasker-Schüler Jubiläumsalmanach, edited by Hajo Jahn and Else-Lasker-Schüler-Gesellschaft, Peter Hammer Verlag, 2015, pp. 275–277.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Nach dem Exil: Remigration als künstlerische Rückkehr / After Exile – Remigration as Artistic Return.” Neue/Alte Heimat. R/emigration von Künstlerinnen und Künstlern nach 1945 = New/old homeland. r/emigration of artists after 1945 (Schriftenreihe des Kunsthaus Dahlem), edited by Dorothea Schöne, exh. cat. Kunsthaus Dahlem, Berlin, 2017, pp. 10–57.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Abbo in Exile, oder: Von der Schwierigkeit kulturellen Über-Setzens / Abbo in Exile, or: On the Difficulty of Cultural Translation.” Jussuf Abbo, edited by Dorothea Schöne, exh. cat. Kunsthaus Dahlem, Berlin, 2019, pp. 99–125.

Jussuf Abbo, edited by Dorothea Schöne, exh. cat. Kunsthaus Dahlem, Berlin, 2019.

Lasker-Schüler, Else, “Jussuff Abbu.” Berliner Börsen-Courier, vol. 55, no. 327, 15 July 1923, p. 5.

Vinzent, Jutta. Identity and Image. Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933–1945) (Schriften der Guernica-Gesellschaft, 16). VDG, 2006.

Zucker, Heinrich, and R. S. Zuriel, Lawyer. Letter to Entschädigungsamt Berlin (Estate of Jussuf Abbo, Brighton, 11 May 1959).

Word Count: 282

Word Count: 4

- https://www.gedenktafeln-in-berlin.de/nc/gedenktafeln/gedenktafel-anzeige/tid/jussuf-abbo/ https://www.tagesspiegel.de/kultur/juedischer-bildhauer-wiederentdeckt-jussuf-abbo-unverdorben-in-der-hast/22953518.html http://www.agialart.com/Content/uploads/Exhibition/2468_Agial%20Said%20Baalbaki%20Leaflet%20low%20res.pdf

My deepest thanks go to the Abbo family, especially Angela and Sebastian Abbo and the late Jerome Abbo, who kindly introduced me to the works of Abbo in the family estate. I am grateful to Shulamith Behr, Rachel Dickson and Sarah MacDougall, for their help. I would like to express my gratitude to Dorothea Schöne from Kunsthaus Dahlem for her continued enthusiasm for the work of Jussuf Abbo and her commitment to remembering his work. I am grateful to the Ben Uri Archive, London, and to the Sprengel Museum Hannover, Kurt Schwitters Archive, with special thanks to Karin Orchard for allowing me to reproduce the illustrations used in this entry.

Word Count: 111

London, GB (1935–1953).

1 Grove Terrace, Highgate, London N1 (residence, c. 1935–1936); 7 Lambolle Road, Hampstead, London NW3 (studio, c. 1938–1945); ? Parkhill Road, Hampstead, London NW3 (residence, 1938); Strathray Gardens, Belsize Park, London NW3 (residence, 1938–1939); ? Byne Road, Sydenham, London SE26 (residence, c. 1944–1947).

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Jussuf Abbo." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5138-7740597, last modified: 03-11-2022.

-

Kurt SchwittersArtistPoetLondon

The artist and poet Kurt Schwitters lived in London between 1941 and 1945, where he stood in contact to émigré and local artists, before moving to the Lake District.

Word Count: 27

Freie Deutsche KulturNewsletterLondonThe Free German League of Culture was an association of emigrant artists and authors who organised exhibitions, concerts and lectures. The events were announced in the Freie Deutsche Kultur newsletter.

Word Count: 30

Ludwig Meidner, Drawings 1920–1922 and 1935–49, Else Meidner, Paintings and Drawings 1935–1949ExhibitionLondonIn 1949, a joint exhibition of works by Ludwig and Else Meidner opened at the Ben Uri Art Gallery. It was the first solo exhibition of the artists in London.

Word Count: 29

Roland, Browse & DelbancoGalleryArt DealerLondonÉmigré art historians and art dealers, Henry Roland and Gustav Delbanco, along with Lillian Browse, opened their Mayfair gallery, Roland, Browse & Delbanco, in 1945.

Word Count: 24