Archive

John Heartfield

- John

- Heartfield

- 19-06-1891

- Schmargendorf (DE)

- 26-04-1968

- Berlin (GDR)

- ArtistGraphic DesignerFotomonteur (mounter of photographs)

After escaping from his first exile in Prague in December 1938, the political artist John Heartfield lived in London since 1950, working for Picture Post and the publisher Lindsay Drummond.

Word Count: 28

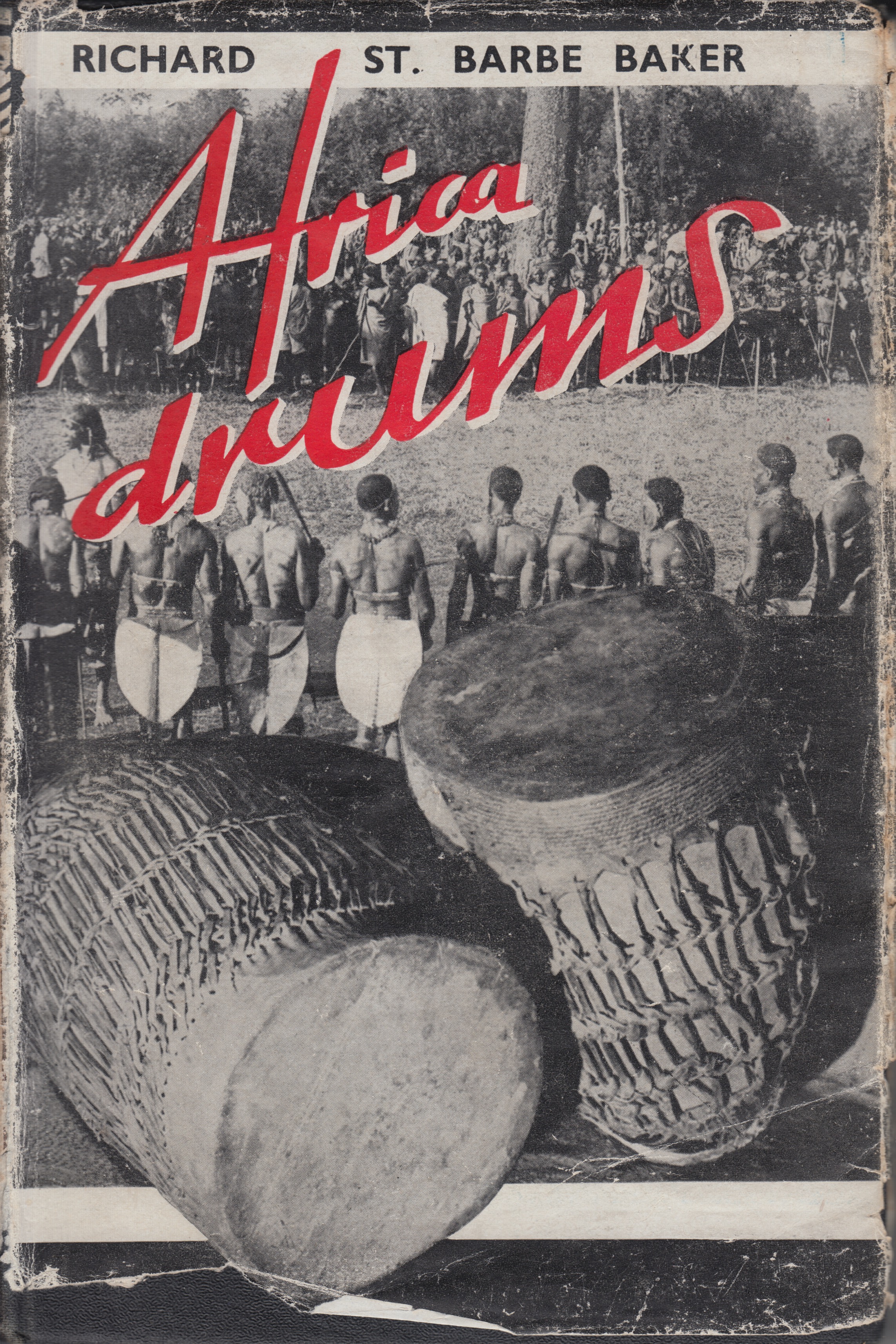

Richard St. Barbe Baker. Africa drums. Lindsay Drummond, 1943, cover design by John Heartfield (METROMOD Archive, © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021). Adam, Ursula. “Helen Reinfrank (1915–2011). Biographische Anmerkungen.” Neuer Nachrichtenbrief der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e.V., no. 43, June 2014, pp. 16–19, www.exilforschung.de/_dateien/neuer-nachrichtenbrief/NNB43_26.6.2014.pdf. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Brinson, Charmian, and Richard Dove. “The Continuation of Politics by Other Means: The Freie Deutscher Kulturbund in London, 1939–1946.” “I didn’t want to float; I wanted to belong to something.” Refugee Organizations in Britain 1933–1945 (Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, 10), edited by Anthony Grenville and Andrea Reiter, Rodopi, 2008, pp. 1–25.

Brinson, Charmian, and Richard Dove, editors. Politics By Other Means. The Free German League of Culture in London 1939–1946. Vallentine Mitchell, 2010.

Buenger, Barbara Copeland. “John Heartfield in London, 1938–45.” Exil. Flucht und Emigration europäischer Künstler 1933–1945, edited by Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann, exh. cat. Neue Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, 1997, pp. 74–79.

Bunbury, H.N., Director of Czech Refugee Trust Fund. Letter for John Heartfield (Akademie der Künste, Archiv Bildende Kunst, 10 November 1939).

Coles, Anthony. John Heartfield. Ein politisches Leben. Böhlau, 2014.

Dörschel, Stephan. “Longing for ‘Bold Constructions’. John Heartfield and the Theatre.” John Heartfield. Photography Plus Dynamite, edited by Angela Lammert et al., exh. cat. Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 2020, pp. 149–157.

Frowein, Cordula. “Ausstellungsaktivitäten der Exilkünstler.” Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 1986, pp. 35–48.

Heartfield, John. “Daumier im ‘Reich’.” Freie Deutsche Kultur, no. 2, 1942, pp. 7–8.

Heartfield, John. Der Schnitt entlang der Zeit. Selbstzeugnisse, Erinnerungen, Interpretationen, edited by Roland März, Verlag der Kunst, 1981.

Larsen, Egon. Inventors’ Scrapbook. Lindsay Drummond, 1947.

Lorant, Stefan. Letter to John Heartfield (Akademie der Künste, Archiv Bildende Kunst, John-Heartfield-Archiv, 7 October 1938).

Lynx, J.J. The Pen is mightier. The Story of War in Cartoons. Lindsay Drummond, 1946.

Müller-Härlin, Anna. “The Artists’ Section.” Politics By Other Means. The Free German League of Culture in London 1939–1946, edited by Charmian Brinson and Richard Dove, Vallentine Mitchell, 2010, pp. 54–73.

Read, Herbert. “Zum 50. Geburtstag von John Heartfield.” Freie Deutsche Kultur, no. 6, 1941, p. 6.

Schultz, Anna. “John Heartfield. A Political Artist’s Exile in London.” Burning Bright. Essays in the Honour of David Bindman, edited by Diana Dethloff et al., UCL Press, 2015, pp. 253–263. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1g69z6q.29. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Schultz, Anna. “Uncompromising Mimicry. Heartfield’s Exile in London.” John Heartfield. Photography Plus Dynamite, edited by Angela Lammert et al., exh. cat. Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 2020, pp. 195–202.

St. Barbe Baker, Richard. Africa drums. Lindsay Drummond, 1943.

Vinzent, Jutta. Identity and Image. Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933–1945) (Schriften der Guernica-Gesellschaft, 16). VDG, 2006.

Willimowski, Thomas. Stefan Lorant – Eine Karriere im Exil. wvb, 2005.

Word Count: 424

Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Archiv Bildende Kunst, Papers of John Heartfield.

Word Count: 12

My deepest thanks go to Sylvia Asmus and Katrin Kokot (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main) for providing me with the images of Freie Deutsche Kultur.

Word Count: 27

Prague, Czech Republic (1933–1938), London, GB (1938–1950).

c/o Fred and Diana Uhlman, 47 Downshire Hill, Hampstead, London NW3 (residence, 1939–1940); 1 Jackson Lane, Highgate, London N6 (residence, 1940–1950).

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "John Heartfield." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5138-9615821, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

Herbert ReadArt HistorianArt CriticPoetLondon

The British art historian Herbert Read established himself as a central figure in the London artistic scene in the 1930s and was one of the outstanding supporters of exiled artists.

Word Count: 30

A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939BookLondonSix years after her arrival in London, the photographer Lucia Moholy published her book A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939, on the occasion of the centenary of photography.

Word Count: 27

Freie Deutsche KulturNewsletterLondonThe Free German League of Culture was an association of emigrant artists and authors who organised exhibitions, concerts and lectures. The events were announced in the Freie Deutsche Kultur newsletter.

Word Count: 30

Allies inside GermanyExhibitionLondonOn 3 July 1942, the Allies inside Germany exhibition, organised by the Free German League of Culture, opened in London in an empty shop at 149 Regent Street.

Word Count: 25

Lindsay DrummondPublishing HouseLondonThe artist John Heartfield designed covers for the publishing house Lindsay Drummond, which had an anti-fascist programme and published books by emigrated authors such as Wilhelm Necker and Felix Langer.

Word Count: 30

St. George’s GalleryArt GalleryLondonIn 1943, the art dealer Lea Bondi Jaray, with support of Otto Brill, also exiled from Vienna, took over St. George’s Gallery in Mayfair, exhibiting contemporary British and continental art.

Word Count: 30

Die ZeitungNewspaperLondonFrom 1941 to 1945, the émigré German-language newspaper Die Zeitung was published in London, reporting on the war on the continent and on the situation in Germany.

Word Count: 25

LilliputMagazineLondonThe magazine Lilliput, founded by the émigré journalist Stefan Lorant in 1937, gave work to emigrated artists and photographers such as Kurt Hutton, Walter Suschitzky, Walter Trier and Edith Tudor-Hart.

Word Count: 29

Ludwig Meidner, Drawings 1920–1922 and 1935–49, Else Meidner, Paintings and Drawings 1935–1949ExhibitionLondonIn 1949, a joint exhibition of works by Ludwig and Else Meidner opened at the Ben Uri Art Gallery. It was the first solo exhibition of the artists in London.

Word Count: 29