Archive

“The Life of a Station.”

- Photoessay

“The Life of a Station.”

Word Count: 5

- Tim Gidal

- 1939

- 1939

Victoria Station, Victoria, London SW1.

- English

- London (GB)

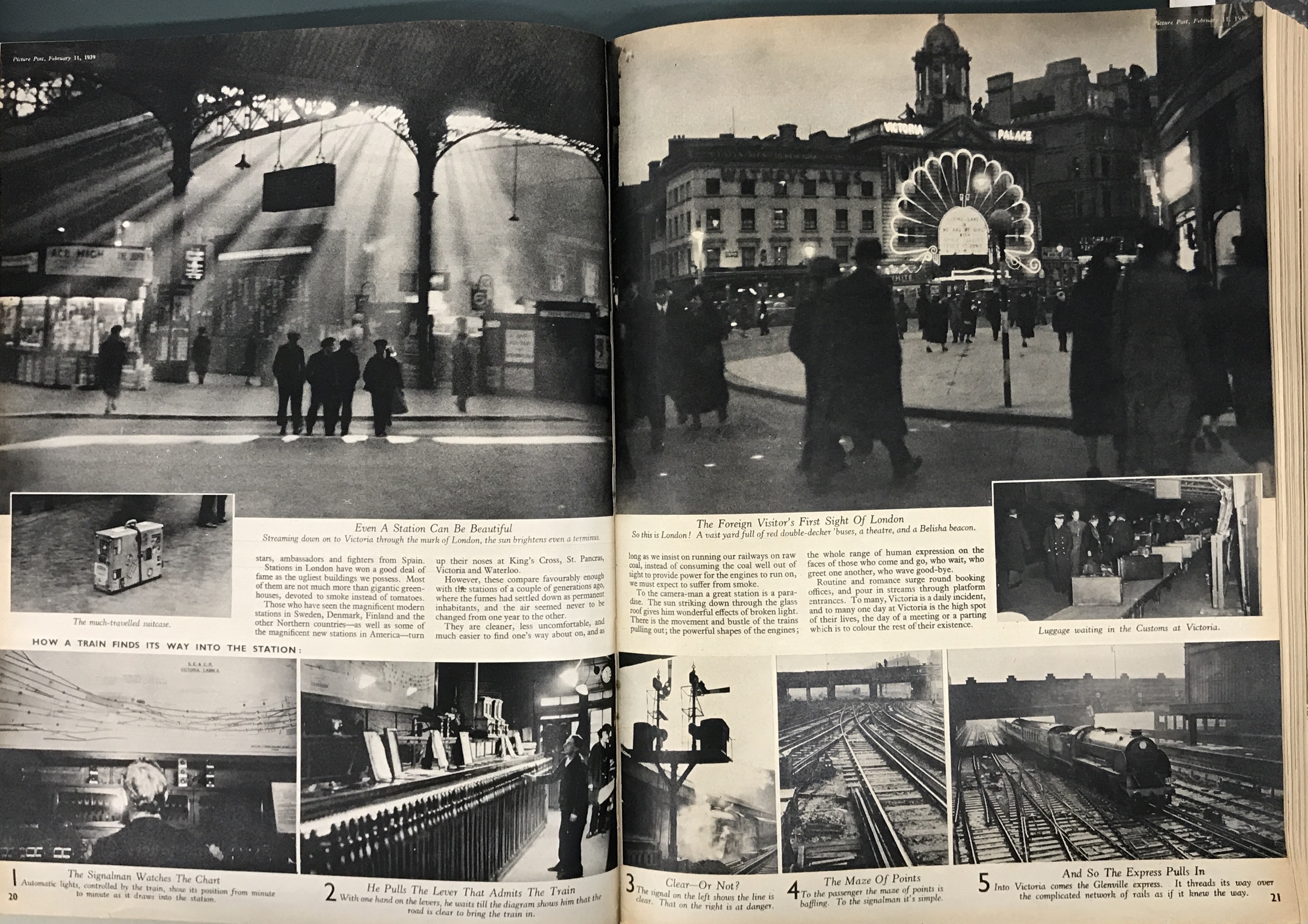

Photographer Tim N. Gidal’s first reportage for Picture Post magazine after his emigration to London was devoted to Victoria Station, observing travellers and their companions as they depart and arrive.

Word Count: 31

Tim N. Gidal. “The Life of a Station.” Picture Post, vol. 2, no. 6, 11 February 1939, pp. 13.

Tim N. Gidal. “The Life of a Station.” Picture Post, vol. 2, no. 6, 11 February 1939, pp. 14–15.

Tim N. Gidal. “The Life of a Station.” Picture Post, vol. 2, no. 6, 11 February 1939, pp. 16–17.

Tim N. Gidal. “The Life of a Station.” Picture Post, vol. 2, no. 6, 11 February 1939, pp. 18–19.

Tim N. Gidal. “The Life of a Station.” Picture Post, vol. 2, no. 6, 11 February 1939, pp. 20–21.

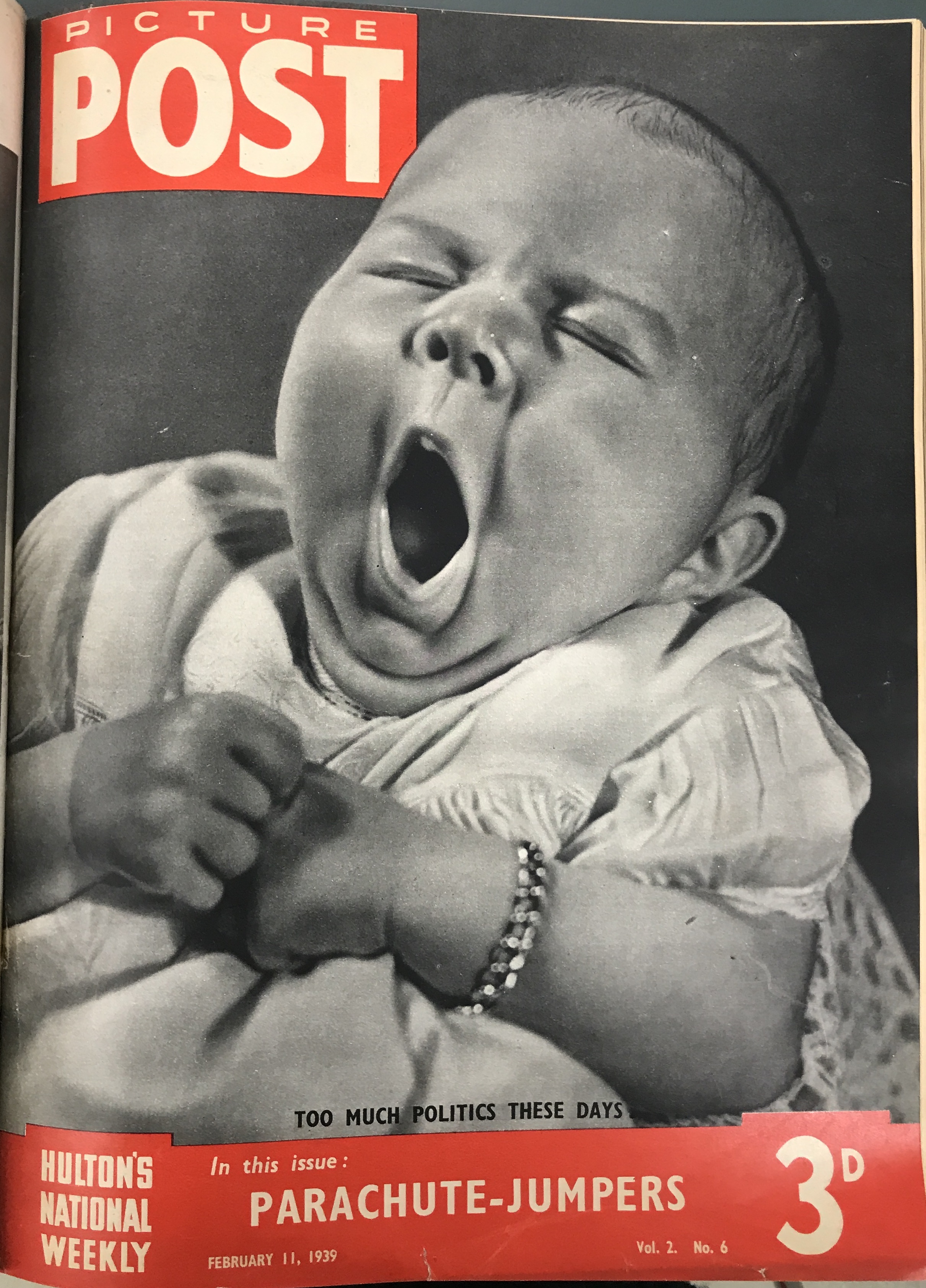

Picture Post, vol. 2, no. 6, 11 February 1939, cover (Private Archive). Issue containing Tim N. Gidal’s photo-essay “The Life of a Station”.

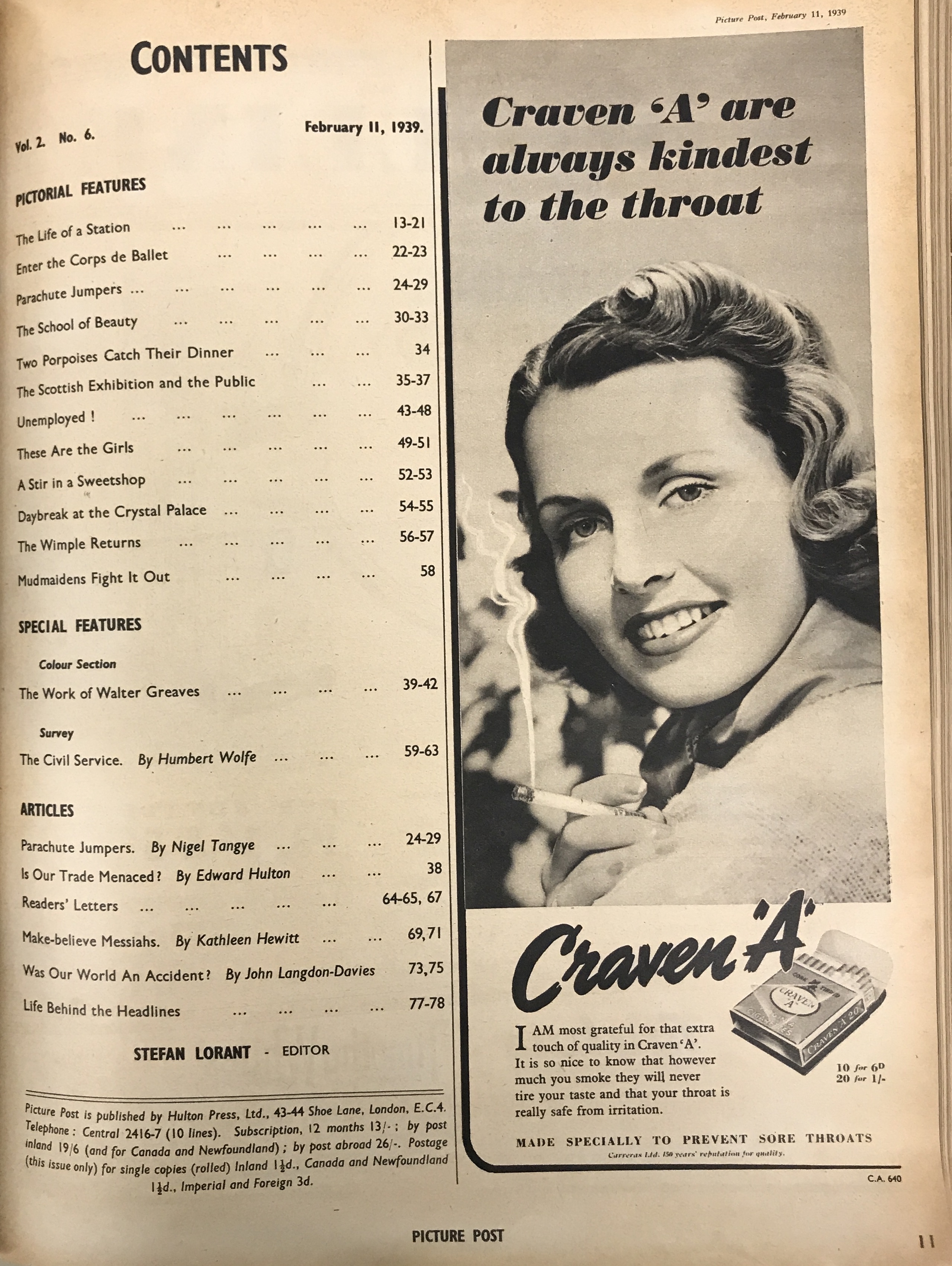

Picture Post, vol. 2, no. 6, 11 February 1939, list of contents (Private Archive). Tim N. Gidal’s photo-essay “The Life of a Station” appears at the top. Dogramaci, Burcu. “Der Kreis um Stefan Lorant. Von der Münchner Illustrierten Presse zur Picture Post.” Netzwerke des Exils. Künstlerische Verflechtungen, Austausch und Patronage nach 1933, edited by Burcu Dogramaci and Karin Wimmer, Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2011, pp. 163–183.

Dogramaci, Burcu, and Helene Roth. “Fotografie als Mittler im Exil: Fotojournalismus bei Picture Post in London und Fototheorie und -praxis an der New School for Social Research in New York.” Vermittler*innen zwischen den Kulturen, edited by Inge Hansen-Schaberg et al., special issue of Zeitschrift für Museum und Bildung, no. 86–87, 2019, pp. 13–44.

Eskildsen, Ute. “Der Beginn einer Karriere am Ende der Weimarer Republik.” Tim Gidal – Bilder der 30er Jahre, exh. cat. Fotografisches Kabinett, Museum Folkwang, Essen, 1984, pp. 3–6.

Gidal, Tim N. “War in the Holyland.” Picture Post, vol. 1, no. 6, 1938, pp. 18–22.

Gidal, Tim N. Deutschland – Beginn des modernen Photojournalismus (Bibliothek der Photographie, 1). Bucher Verlag, 1972.

Gidal, Tim N. “Modern photojournalism – The first years.” creative camera, July/August 1982, pp. 572–579.

Gidal, Tim Nachum. Die Juden in Deutschland von der Römerzeit bis zur Weimarer Republik. Bertelsmann, 1988.

Gidal, Tim N. Chronisten des Lebens. Die moderne Fotoreportage. Edition q, 1993.

Hallett, Michael. Stefan Lorant. Godfather of Photojournalism. Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Holzer, Anton. Rasende Reporter. Eine Kulturgeschichte des Fotojournalismus. Primus Verlag, 2014.

Holzer, Anton. “Nachrichten und Sensationen. Die Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung und der deutsche Fotojournalismus vor 1945.” Die Erfindung der Pressefotografie. Aus der Sammlung Ullstein 1894–1945, exh. cat. Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, 2017, pp. 26–37.

Hopkinson, Amanda. “Picture Post: ‘Strongly political and anti-Fascist’.” Insiders Outsiders. Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Visual Culture, edited by Monica Bohm-Duchen, Lund Humphries, 2019, pp. 121–127.

Hopkinson, Tom, editor. Picture Post 1938–50. Penguin Books, 1979.

Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 1986.

Münchner Illustrierte Presse, Munich, 1923–1945.

Osman, Colin. “Der Einfluß deutscher Fotografen im Exil auf die britische Pressefotografie.” Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 1986, pp. 83–87.

Picture Post, London, 1938–1957.

Schaber, Irme. “‘Die Kamera ist ein Instrument der Entdeckung...’. Die Großstadtfotografie der fotografischen Emigration der NS-Zeit in Paris, London und New York.” Exilforschung. Ein internationales Jahrbuch, vol. 20: Metropolen des Exils, edited by Claus-Dieter Krohn et al., edition text + kritik, 2002, pp. 53–73.

Schumann, Klaus. “Der Mann mit den sechs Leben. Die ungewöhnliche Karriere des Stefan Lorant.“ Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14/15 December 1985.

Willimowski, Thomas. Stefan Lorant – Eine Karriere im Exil. wvb, 2005.

Wyers, Frank, and Klaus Honnef. Und sie haben Deutschland verlassen ... müssen. Fotografen und ihre Bilder 1928–1997, exh. cat. Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn, Bonn, 1997.

Word Count: 404

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "“The Life of a Station.”." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5140-11015302, last modified: 12-05-2021.

-

LilliputMagazineLondon

The magazine Lilliput, founded by the émigré journalist Stefan Lorant in 1937, gave work to emigrated artists and photographers such as Kurt Hutton, Walter Suschitzky, Walter Trier and Edith Tudor-Hart.

Word Count: 29

Tim GidalPhotographerPublisherArt HistorianNew YorkTim Gidal was a German-Jewish photographer, publisher and art historian emigrating in 1948 emigrated to New York. Besides his teaching career, he worked as a photojournalist and, along with his wife Sonia Gidal, published youth books.

Word Count: 35

New School for Social ResearchAcademy/Art SchoolPhoto SchoolUniversity / Higher Education Institute / Research InstituteNew YorkDuring the 1940s and 1950s emigrated graphic designers and photographers, along with artists and intellectuals, were given the opportunity to held lectures and workshops at the New School for Social Research.

Word Count: 31