Archive

A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939

- Book

- A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939

Word Count: 5

- Lucia Moholy

- 1939

- 1939

Lucia Moholy, 39 Mecklenburgh Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1.

- London (GB)

Six years after her arrival in London, the photographer Lucia Moholy published her book A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939, on the occasion of the centenary of photography.

Word Count: 27

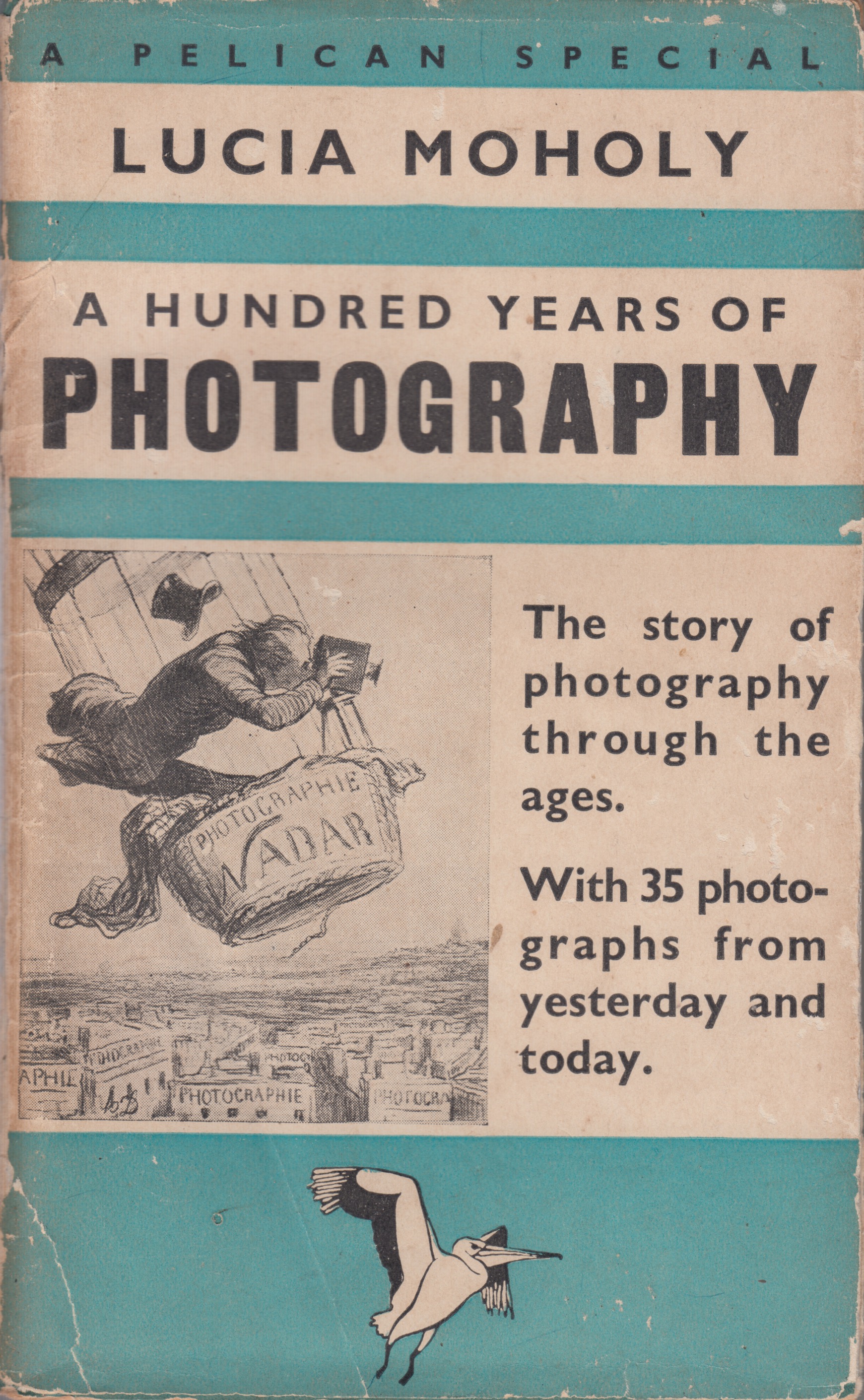

Lucia Moholy. A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939. Penguin Books, 1939, cover (METROMOD Archive).

Lucia Moholy. A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939. Penguin Books, 1939, bastard title with Daumier’s quote “Je suis de mon temps” (METROMOD Archive).

Lucia Moholy. A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939. Penguin Books, 1939, title page (METROMOD Archive).

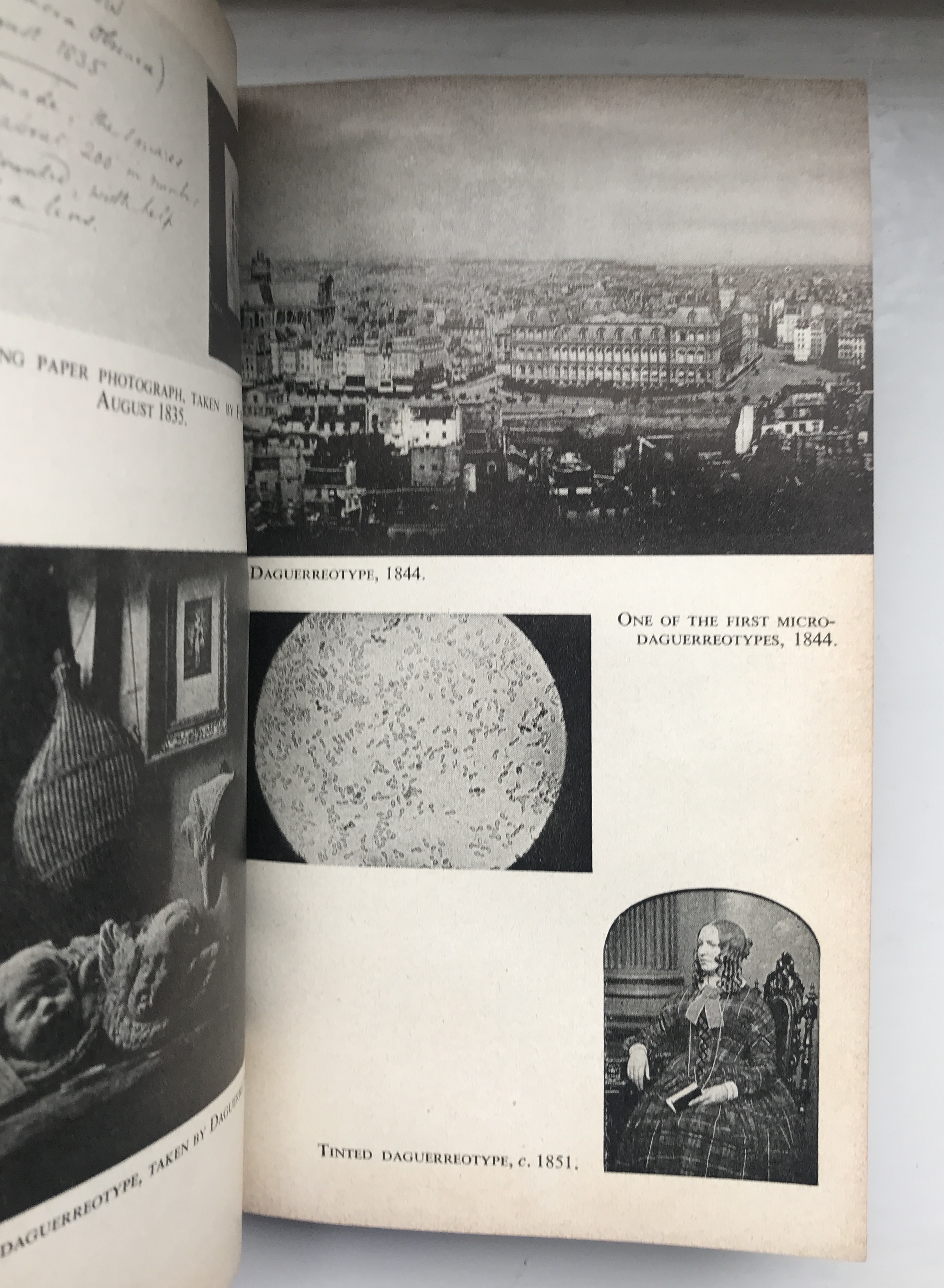

Lucia Moholy. A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939. Penguin Books, 1939, page with daguerreotypes (METROMOD Archive).

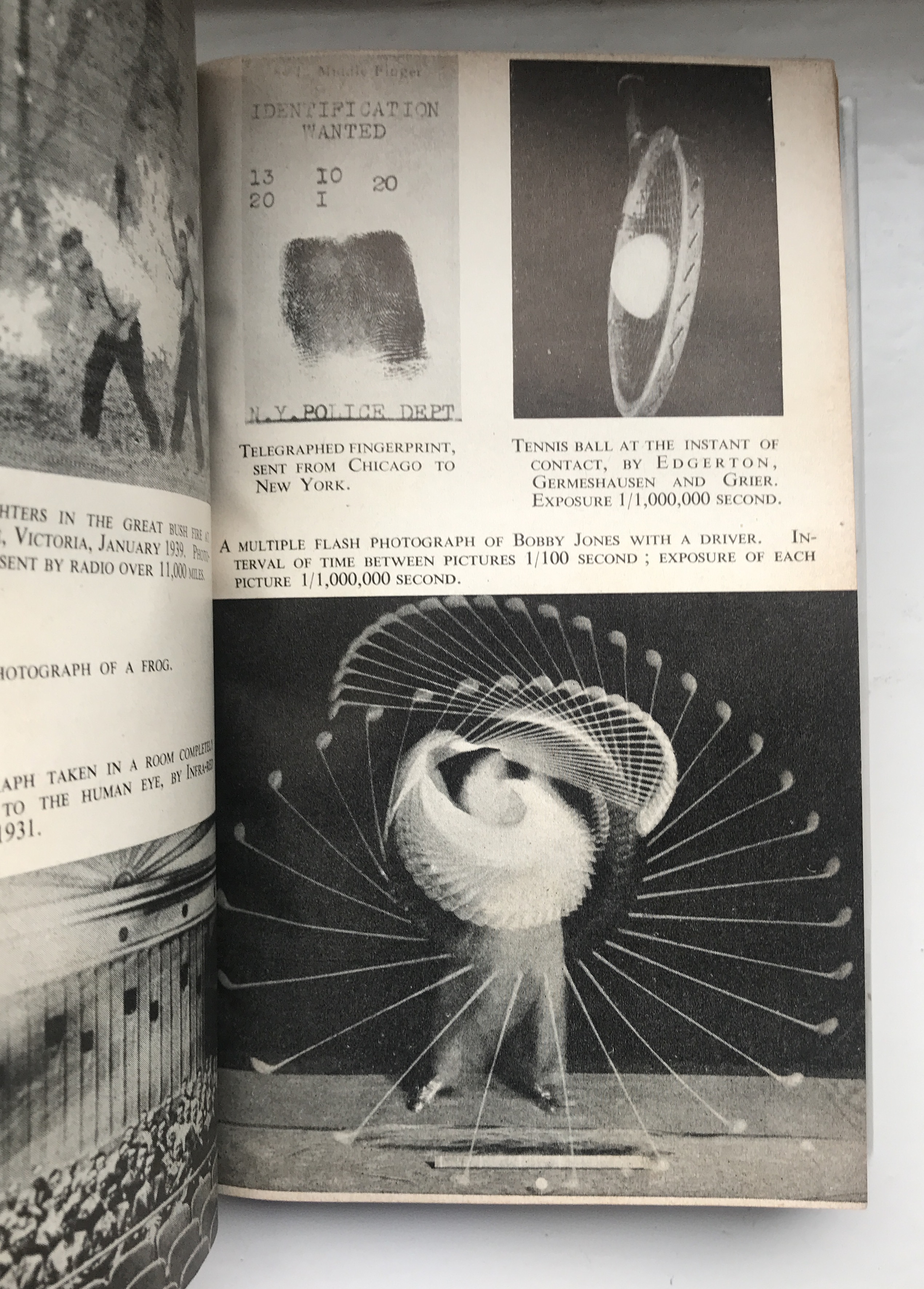

Lucia Moholy. A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939. Penguin Books, 1939, page with a multiple flash photograph of the golfer Bobby Jones with a driver (METROMOD Archive). Freund, Gisèle. La Photographie en France au dix-neuvième Siècle. La Maison des Amis des Livres, 1936.

Gernsheim, Helmut. New Photo Vision. Fountain Press, 1942.

Gernsheim, Helmut, and Alison Gernsheim. The History of Photography from the Earliest Use of the Camera Obscura in the Eleventh Century up to 1914. Oxford University Press, 1955.

Gernsheim, Helmut, and Alison Gernsheim. The History of Photography from the Earliest Use of the Camera Obscura to the Beginning of the Modern Era. McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1969.

Gombrich, Ernst H. “Daumier, Honoré; Wartmann, Wilhelm: 240 Lithographien (review).” The Burlington Magazine, no. 89, 1947, pp. 231–232.

Halwani, Miriam [Miriam Szwast]. Geschichte der Fotogeschichte 1839–1939. Reimer Verlag, 2012.

Halwani, Miriam. Lucia Moholy. Fotogeschichte schreiben (Sammlung Fotografie, Museum Ludwig, 2), exh. cat. Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 2019.

Heartfield, John. “Daumier im ‘Reich’.” Freie Deutsche Kultur, no. 2, 1942, pp. 7–8.

Hoiman, Sibylle. “Einleitung.” Lucia Moholy. A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939. Hundert Jahre Fotografie 1839–1939 (Bauhäusler. Dokumente aus dem Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, vol. 4), Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, 2016, pp. 8–13.

Maggi, Angelo. “A Hundred Years of Photography. A Critical Rereading of an Innovative Contribution.” Lucia Moholy (1894–1989) between Photography and Life (Fotografia, 3), edited by Nicoletta Ossanna Cavadini, exh. cat. m.a.x. museo, Chiasso, 2012, pp. 41–47.

Mitchell, Carla, and John March. Another Eye. Women Refugee Photographers after 1933, exh. cat. Four Corners, London, 2020.

Moholy, Lucia. A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939. Penguin Books, 1939.

Müller, Ulrike. “Lucia Moholy.” Frauen am Bauhaus. Wegweisende Künstlerinnen der Moderne, edited by Patrick Rössler and Elizabeth Otto, translated by Birgit van der Avoort, Knesebeck, 2019, pp. 62–67.

Newhall, Beaumont. Photography. A short critical history. MoMA, 1938.

Newhall, Beaumont. “Lucia Moholy: A Hundred Years of Photography (review).” The Art Bulletin, vol. 23, no. 3, 1941, pp. 246–247.

Sachsse, Rolf. Lucia Moholy. Edition Marzona, 1985.

Sachsse, Rolf. Lucia Moholy. Bauhaus-Fotografin. Bauhaus-Archiv, 1995.

Schuldenfrei, Robin. “Images in Exile: Lucia Moholy’s Bauhaus Negatives and the Construction of the Bauhaus Legacy.” History of Photography, vol. 37, no. 2, 2013, pp. 182–203.

Schwarz, Heinrich. David Octavius Hill. Der Meister der Photographie. Insel Verlag, 1931.

Stenger, Erich. Geschichte der Photographie (Abhandlungen und Berichte des Deutschen Museums, vol. 1, no. 6). VDI-Verlag, 1929.

Taft, Robert. Photography and the American Scene: A social history, 1839–1889. Macmillan, 1938.

Valdivieso, Mercedes. “Eine ‘symbiotische Arbeitsgemeinschaft’ und die Folgen – Lucia und László Moholy-Nagy.” Liebe Macht Kunst. Künstlerpaare im 20. Jahrhundert, edited by Renate Berger, Böhlau, 2000, pp. 6–85.

Word Count: 360

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939 ." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5140-11251867, last modified: 09-05-2021.

-

Edith Tudor-HartPhotographerLondon

The Viennese photographer Edith Tudor-Hart emigrated to England in 1933 and made a name with her photographs focusing on questions of class, social exclusion and the lives of marginalised people.

Word Count: 29

Otti BergerTextile DesignerWeaverLondonThe textile designer and weaver Otti Berger lived in exile in London in 1937/38, where she sought to open up a new field of activity.

Word Count: 24

Margaret LeischnerTextile DesignerLondonThe designer Margaret Leischner lived in England from 1938, worked for textile and furniture companies, taught at the Royal College of Art and was honoured as Royal Designer for Industry.

Word Count: 29

Focus on Architecture and SculptureBookLondonFocus on Architecture and Sculpture by émigré photographer Helmut Gernsheim brought together his work and experience as a photographer for the National Buildings Record (NBR).

Word Count: 25

St. George’s GalleryArt GalleryLondonIn 1943, the art dealer Lea Bondi Jaray, with support of Otto Brill, also exiled from Vienna, took over St. George’s Gallery in Mayfair, exhibiting contemporary British and continental art.

Word Count: 30

László Moholy-NagyPhotographerGraphic DesignerPainterSculptorLondonLászló Moholy-Nagy emigrated to London in 1935, where he worked in close contact with the local avantgarde and was commissioned for window display decoration, photo books, advertising and film work.

Word Count: 30

John HeartfieldArtistGraphic DesignerFotomonteur (mounter of photographs)LondonAfter escaping from his first exile in Prague in December 1938, the political artist John Heartfield lived in London since 1950, working for Picture Post and the publisher Lindsay Drummond.

Word Count: 28

The Story of ArtBookLondonThe Story of Art by the émigré art historian Ernst H. Gombrich was published in 1950 with Phaidon Press. The book is a comprehensive and accessible introduction to visual culture.

Word Count: 29

The Street Markets of LondonPhotobookLondonIn 1936, émigré photographer László Moholy-Nagy realised The Street Markets of London together with the journalist Mary Benedetta, setting the book within the overarching theme of urban photography.

Word Count: 28