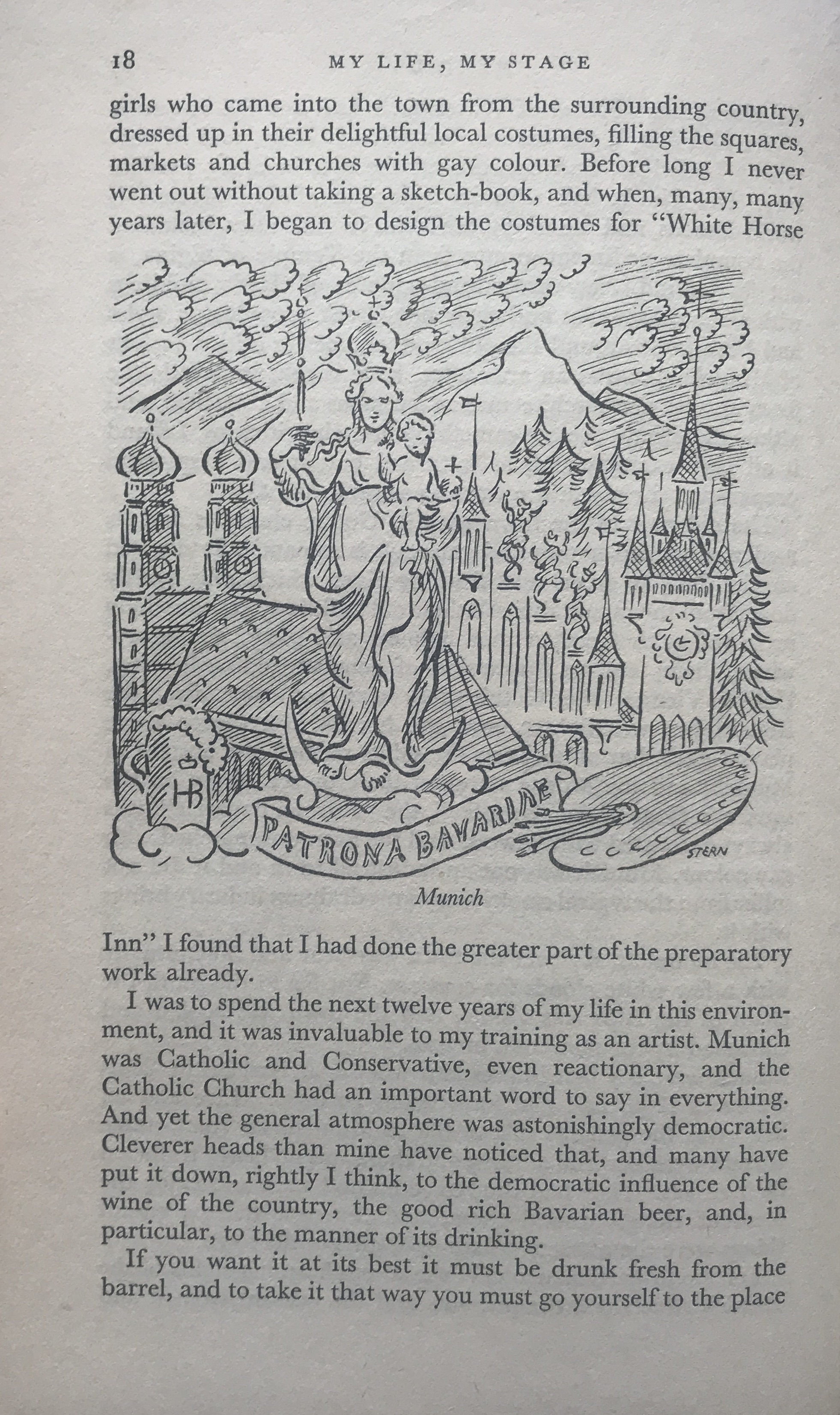

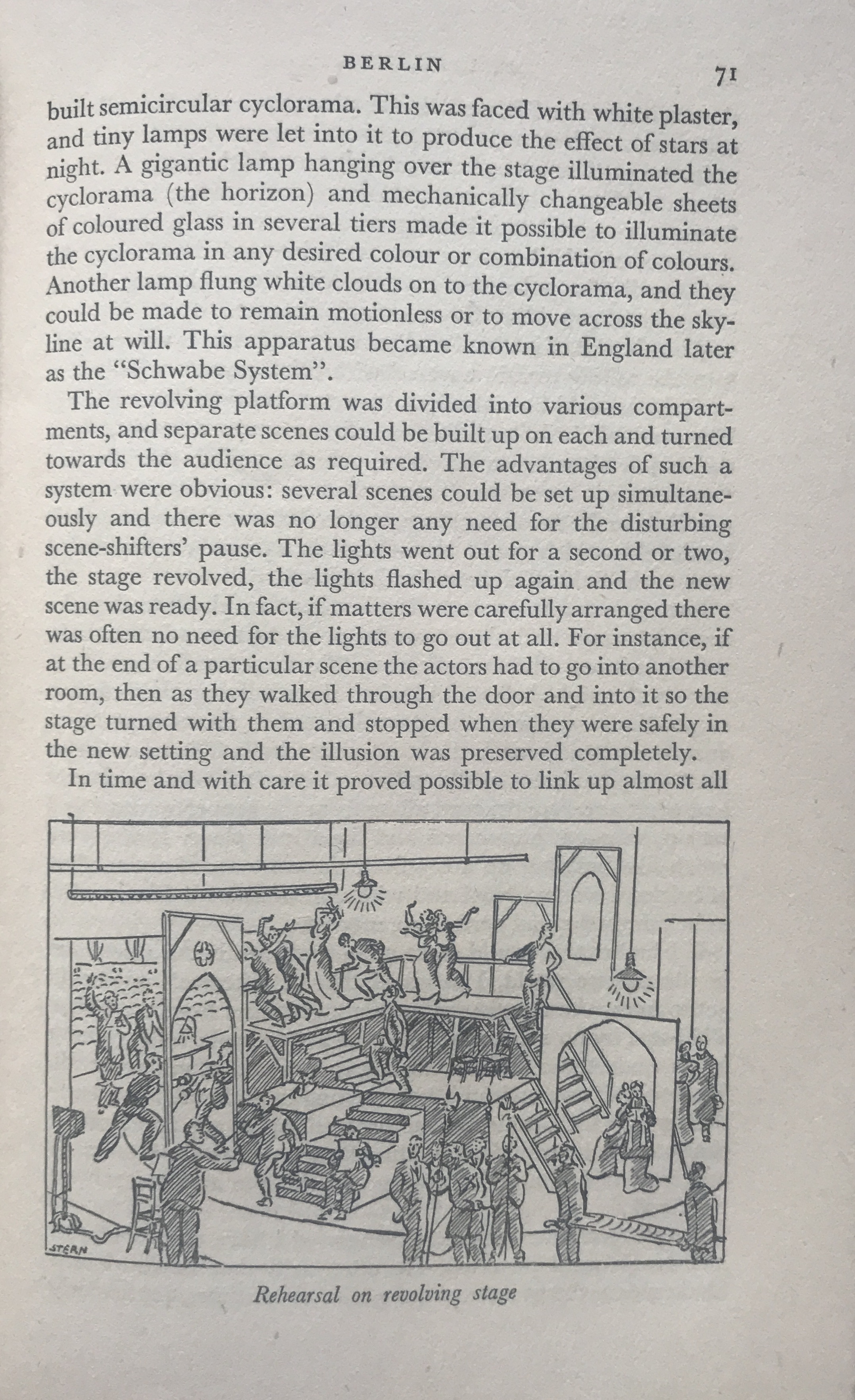

My Life, My Stage is the illustrated autobiography of theatre artist, and costume and set designer Ernest (Ernst) Stern (1876–1954). In his book, he looks back on his career in the 1910s and 1920s. Stern was born in Bucharest, lived in Vienna and studied at the Munich Academy before moving to Berlin, where he worked with the director and head of the Deutsches Theater, Max Reinhardt, between 1906 and 1921. Stern developed fantastic stage decorations and costumes for Reinhardt's plays, ballets and musical pantomimes, which had a decisive influence on the Reinhardt era. Don Carlos (1909), Das Mirakel (1911) and Ein Sommernachtstraum (1913) are worthy of mention. Many of Max Reinhardt’s productions made guest appearances abroad or were conceived as touring pieces, so that Stern’s designs were noticed internationally. For the musical pantomime Sumurum (1910), the artist worked with exoticising elements, drawing on his own memories of the Ottoman-impacted Bucharest of his childhood as well as on the orientalist literature of the 19th century (Stern 1951, 85–87). His costumes and set design for the ballet The Green Flute (1916) also employed exoticisms and evoked a fairy-tale China. From 1918 Stern also worked for the cinema – some famous German silent and sound films bear Ernst Stern’s signature, including Satanas (1920, directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau), Die Bergkatze (1921, directed by Ernst Lubitsch) and Das Wachsfigurenkabinett (1924, costume, directed by Paul Leni). In his memoirs, Stern writes about his work for The Pharaoh’s Wife (1922, directed by Ernst Lubitsch) for which he had to supply 2,000 extras with Egyptian costumes. A drawing in Stern’s autobiography shows the Berlin extras putting on bronze body makeup to transform themselves into ‘authentic’ Egyptians (Stern 1951, 183).

Ernest Stern was closely associated with the director Erik Charell. Not only did he design Charell’s film Der Kongress tanzt (1931), he was also responsible, from as early as 1924, for costumes and stage designs for Erik Charell’s revues, which went on international tours. When the National Socialists came to power, Ernest Stern was in Paris for a performance of Charell’s Das Weiße Rößl. Charell also offered him his first commissions in emigration as a set designer for the film Caravane (1934) in Hollywood and for his circus revue The Flying Trapeze (1935) at the Alhambra Theatre in London (Stern 1951, 245). Ernest Stern lived in London from the end of 1934. On 15 March 1935 he noted in his diary: “... no longer want to return to Germany and work there [...]. I cannot imagine how one could ever live and work in Germany again, it has become an absolute impossibility for me – there is not the slightest prospect of returning there, the regime there is now quite solid! You have to steer your destiny in completely different directions.” (Stern, Diaries, 15 March 1935, translated from German)

Stern’s many international contacts through the touring productions of Reinhardt and Charell were important in building and expanding his professional network. As early as the 1920s, Stern had repeatedly worked in London and, for example, decorated Noël Coward's operetta Bitter Sweet (1929). In 1936, productions such as Young Madame Conti, Can-Can and Follow the Sun were presented at the Savoy Theatre, The London Palladium and the Adelphi Theatre, for which Stern worked with British directors such as Benn W. Levy and William Mollison (see Stern, Diaries, 1 August 1935–4 February 1936). In 1937 Stern was commissioned to design the exterior decoration of Selfridges department store on the occasion of the coronation of George VI and Elizabeth. For the front on Oxford Street, he designed a colourful, flagged decoration; above the entrance was the central group “The Empire's Homage to the Throne” with personifications of the British Dominions, Colonies and Protectorates paying homage to Britannia on the throne. In the following years, Stern continued to be involved with sets (stage design and/or costume) for plays and revues in London theatres. The change of language in his diary – from 1939 Stern wrote partly in English – indicates an increasing adaptation to the new context. Nevertheless, Stern’s autobiography was written in German and translated into English by Edward Fitzgerald.

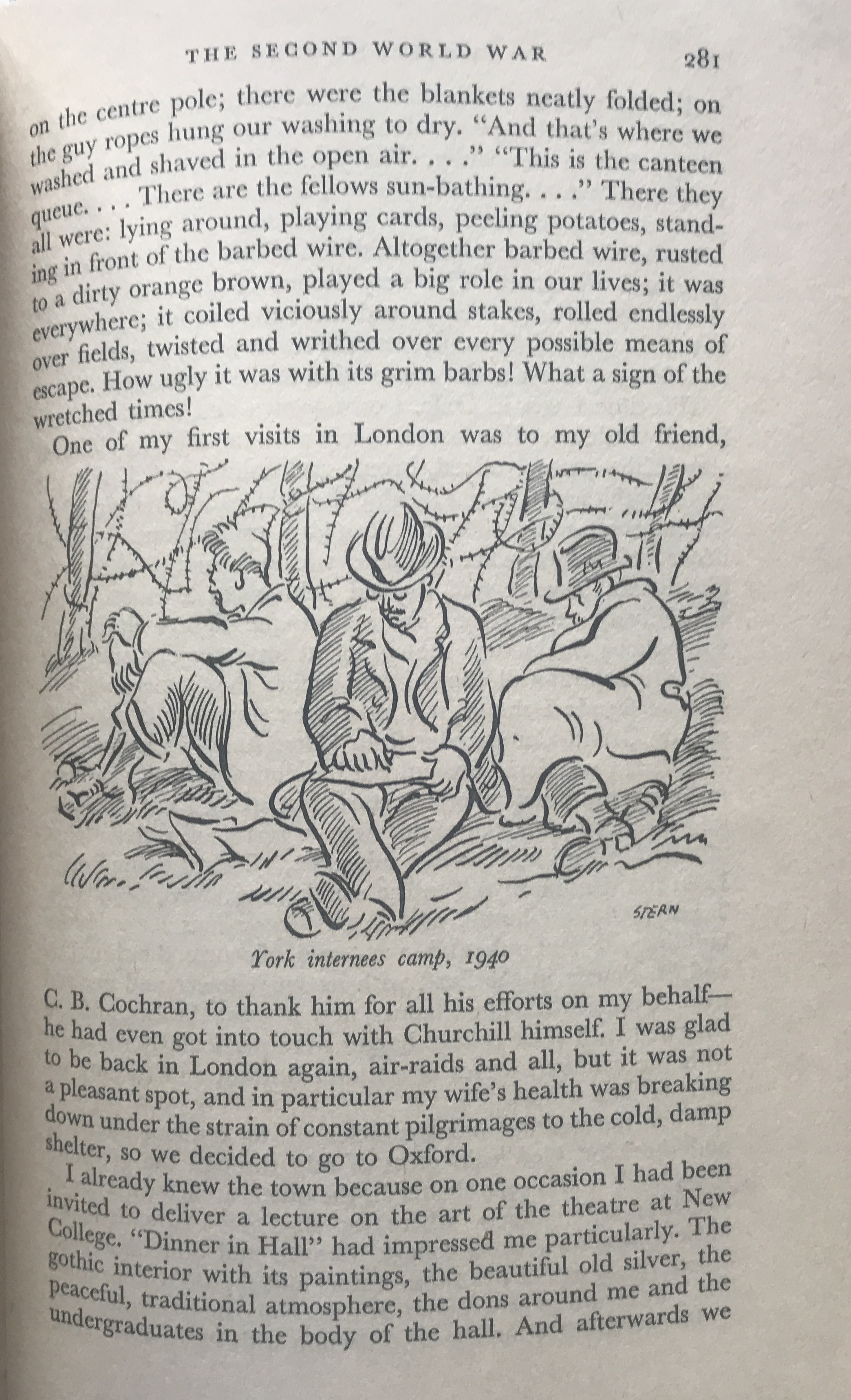

The book was published by Victor Gollancz, a publishing house with a political agenda that had existed since 1927. Gollancz also founded the Left Book Club as a platform for socialist and socially critical authors. For example, Wal Hannington’s The Problem of the Distressed Areas (1937) with photographs by Edith Tudor-Hart was published by Gollancz and distributed to its club members. Gollancz released anti-fascist, pacifist and enlightenment literature: Why I Am a Jew (1943) by Edmond Fleg and What Buchenwald Really Means (1945) and Germany Revisited (1947). In 1960, Victor Gollancz was awarded the “Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels” (German Book Trade Peace Prize) for his commitment to social justice and pacifism. This was the publishing environment in which Ernest Stern’s book appeared, which was not only a theatreman’s memoir of his colourful past in Berlin and elsewhere, but also the autobiography of an emigrant: in his book, Stern looks back on 1933 as the “End of an Epoch”, with accounts of his escape and his time spent in internment in Sutton Coldfield near Birmingham and in York Racecourse, Internment Camp B (July-September 1940) (270–280). The book ends with a bombing raid on London in 1944: “A flying bomb wrecked our flat. Two rooms were completely destroyed, but, fortunately although my studio was damaged, none of my work was destroyed, and that was a great relief. As I have said, we slept in another flat on the ground floor and so we escaped injury. To our astonishment, we were not even greatly excited. It was just our turn. The next morning I even began to sketch the damage.” (Stern 1951, 292) One of these drawings is reproduced in the autobiography.

Although Stern’s autobiography and exile read as a story of artistic success with continuities in theatrical work, Stern suffered from the vagaries of emigration, the anxiety over residency and work permits. In addition, he had hardly been able to export any capital, so was completely dependent on new income. From 1949, Stern received a Civil List pension, which ensured his survival, as he no longer worked for the theatre in the later years of his life for health reasons. His last production was Massenet’s opera Werther in 1952, directed by James Robertson at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London. Stern designed the sets and costumes.

Ernest Stern’s autobiography was published in German by Henschel Verlag in 1955 under the title Ernst Stern. Bühnenbildner bei Max Reinhardt. This German title makes it clear that Stern's work in London exile had gone unnoticed and that he was remembered primarily as an artist closely associated with Reinhardt. My Life, My Stage, meaning the "my", became (again) Max Reinhardt’s stage designs.