Archive

The Street Markets of London

- Photobook

- The Street Markets of London

Word Count: 5

- László Moholy-NagyMary Benedetta

- 1936

- 1936

John Miles Ltd, Amen Corner, St. Paul’s, London EC4.

- English

- London (GB)

In 1936, émigré photographer László Moholy-Nagy realised The Street Markets of London together with the journalist Mary Benedetta, setting the book within the overarching theme of urban photography.

Word Count: 28

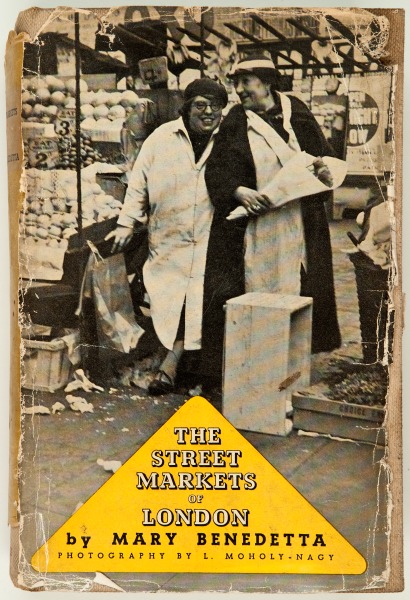

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. John Miles, 1936, cover (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

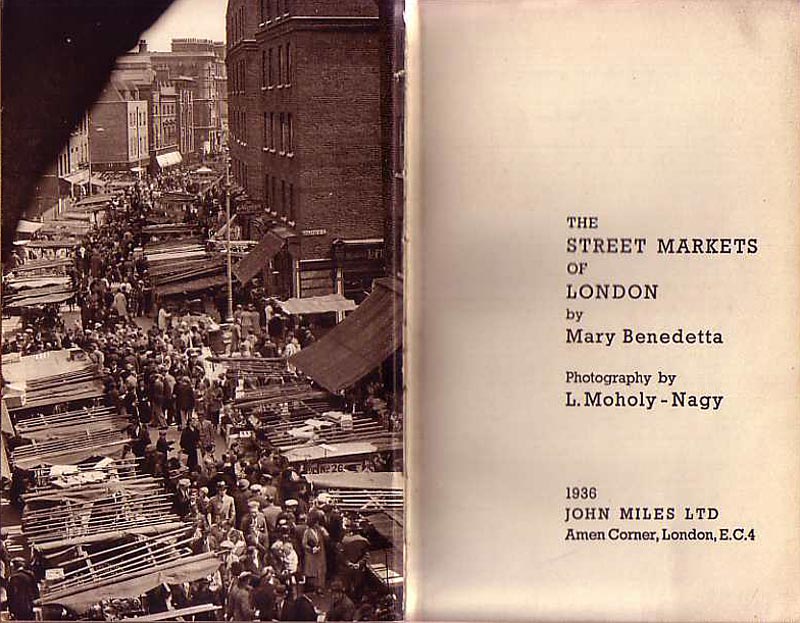

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. John Miles, 1936, title page (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

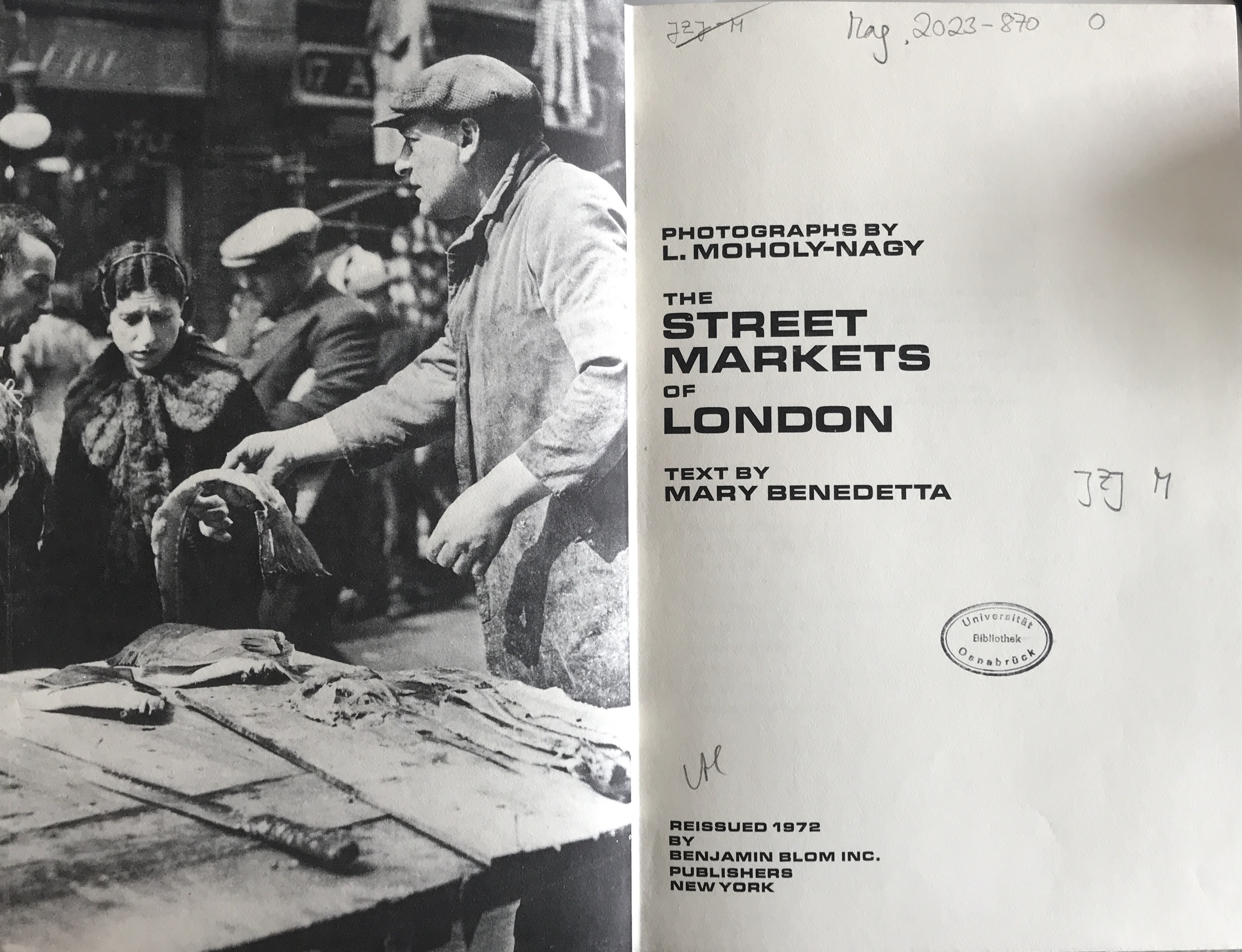

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. (reissued 1972). Benjamin Blom, 1972, title page (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

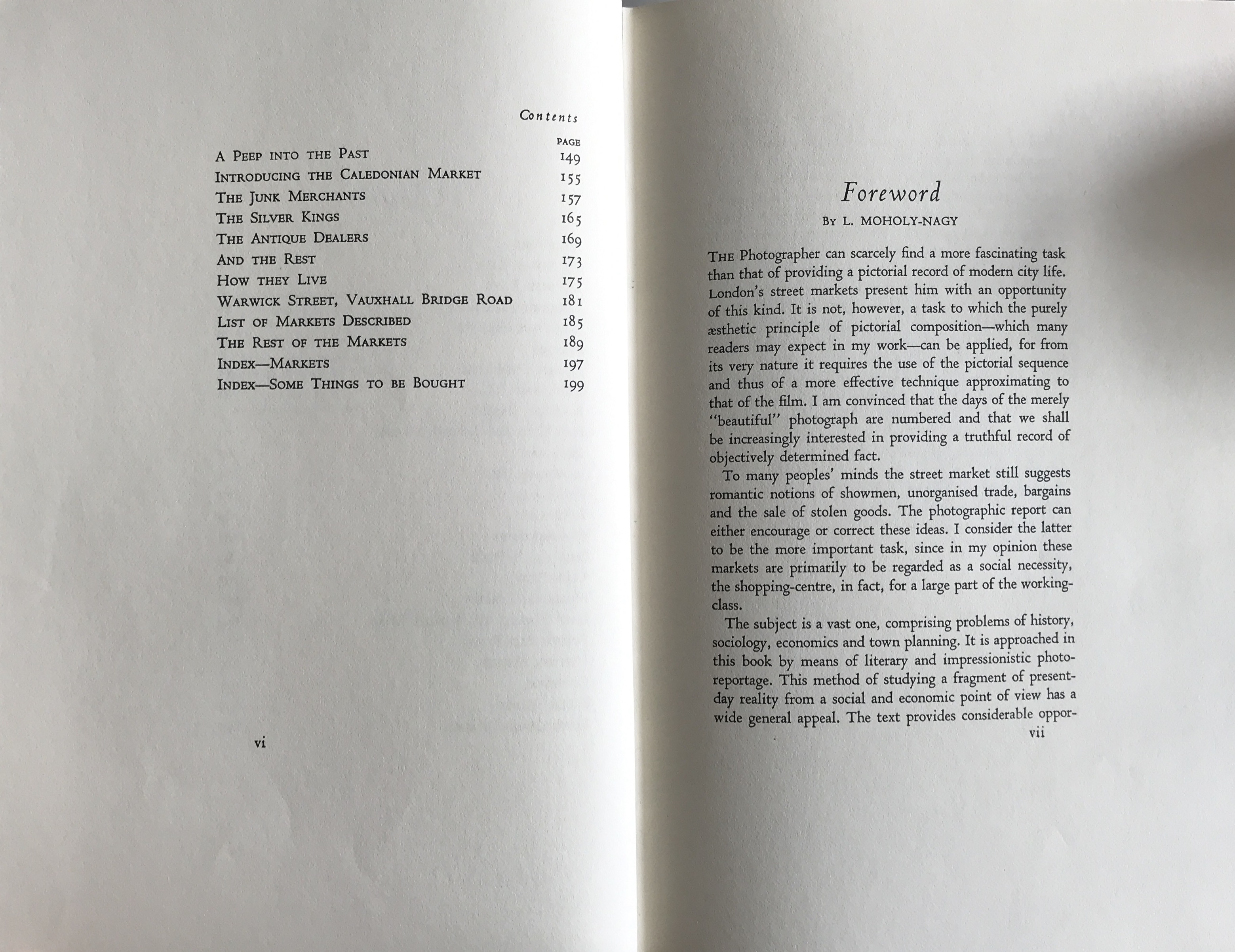

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. (reissued 1972). Benjamin Blom, 1972, p. vii: Foreword by László Moholy-Nagy (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. (reissued 1972). Benjamin Blom, 1972, p. viii: Foreword by László Moholy-Nagy (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. (reissued 1972). Benjamin Blom, 1972, “Petticoat Lane: general view” (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. (reissued 1972). Benjamin Blom, 1972, “Petticoat Lane: The Spectacle Man” and “Petticoat Lane: In a side street. Some Arabian visitors at a second-hand clothes stall” (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. (reissued 1972). Benjamin Blom, 1972, “Petticoat Lane: Alf, the Purse King” and “Petticoat Lane: The wealth of a trinket stall” (© The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

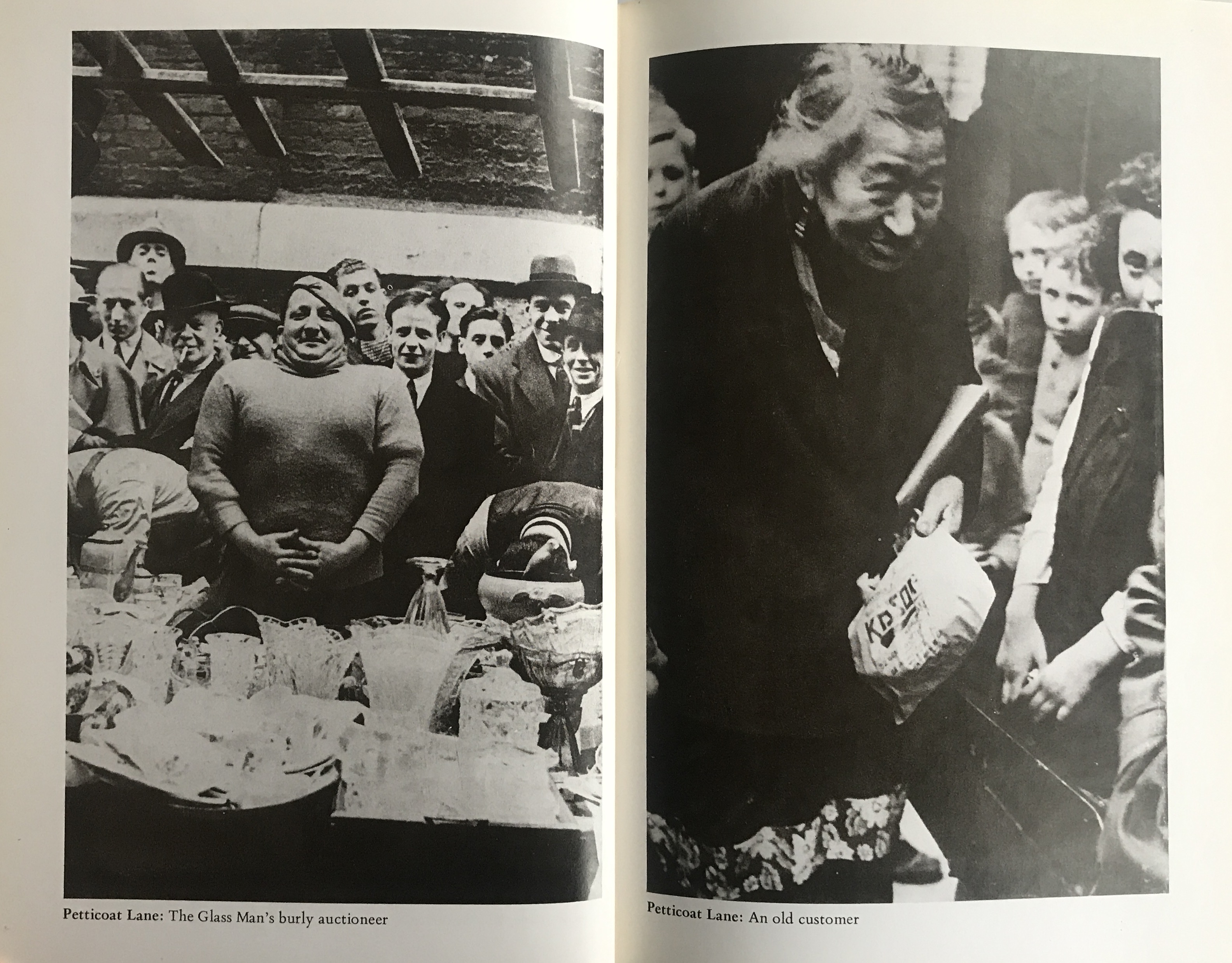

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. (reissued 1972). Benjamin Blom, 1972, “Petticoat Lane: The Glass Man’s burly auctioneer” and “Petticoat Land: An old customer” (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

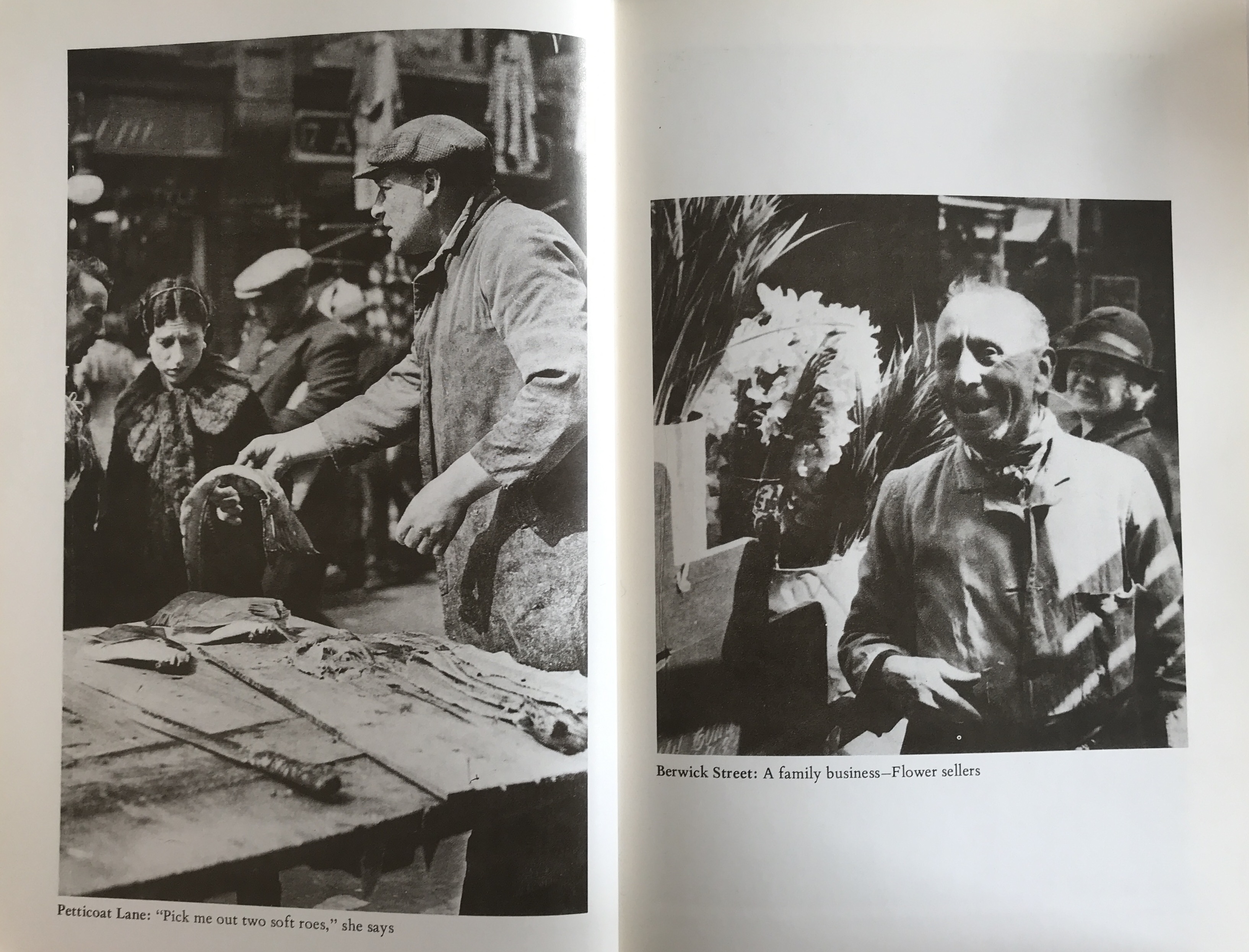

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. (reissued 1972). Benjamin Blom, 1972, “Petticoat Lane: ‘Pick me out two soft roes,’ she says” and “Berwick Street: A family business – Flower sellers” (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

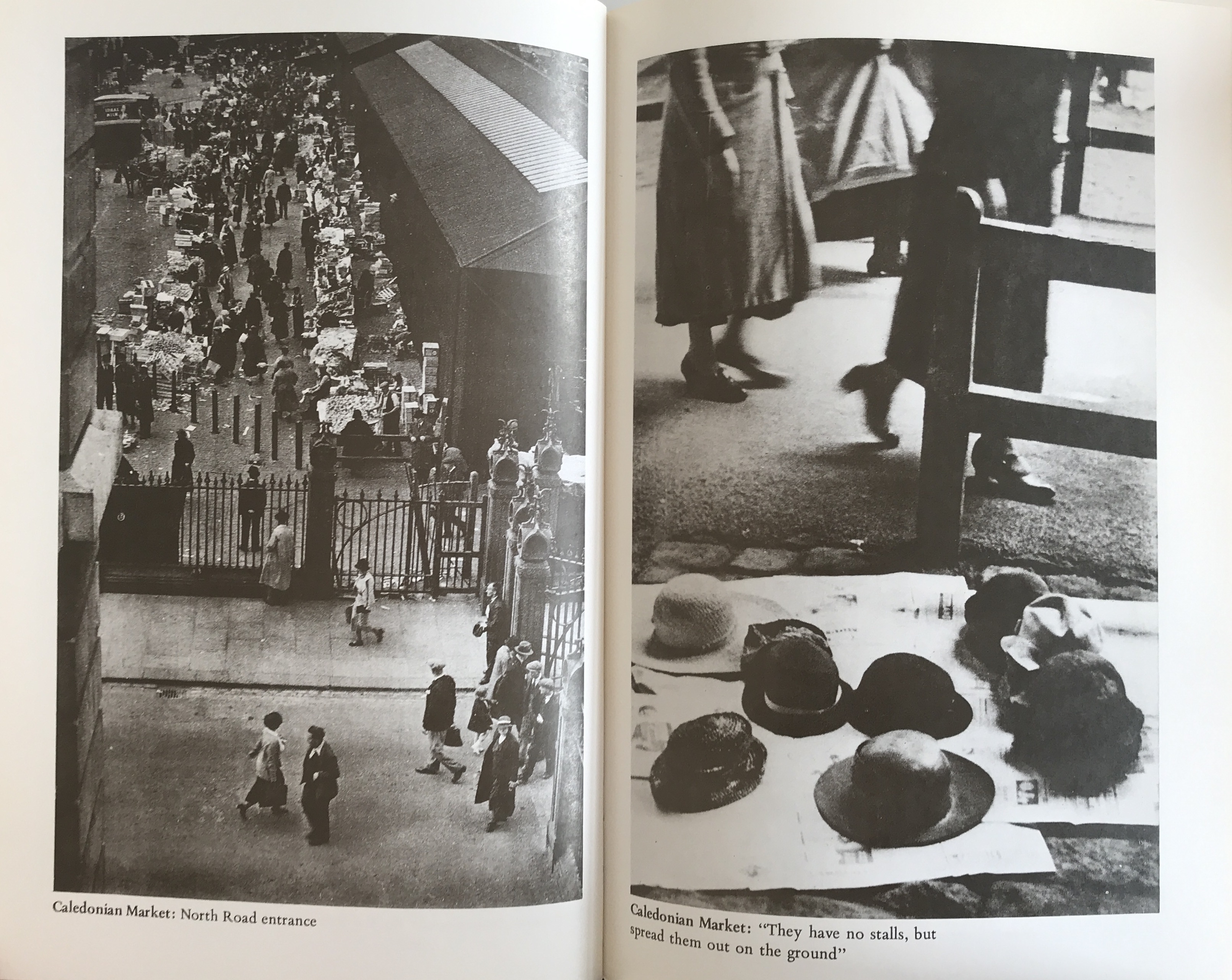

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. Reissued 1972. Benjamin Blom, 1972, “Caledonian Market: North Road entrance” and “Caledonian Market: ‘They have no stalls, but spread them out on the ground’”(Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

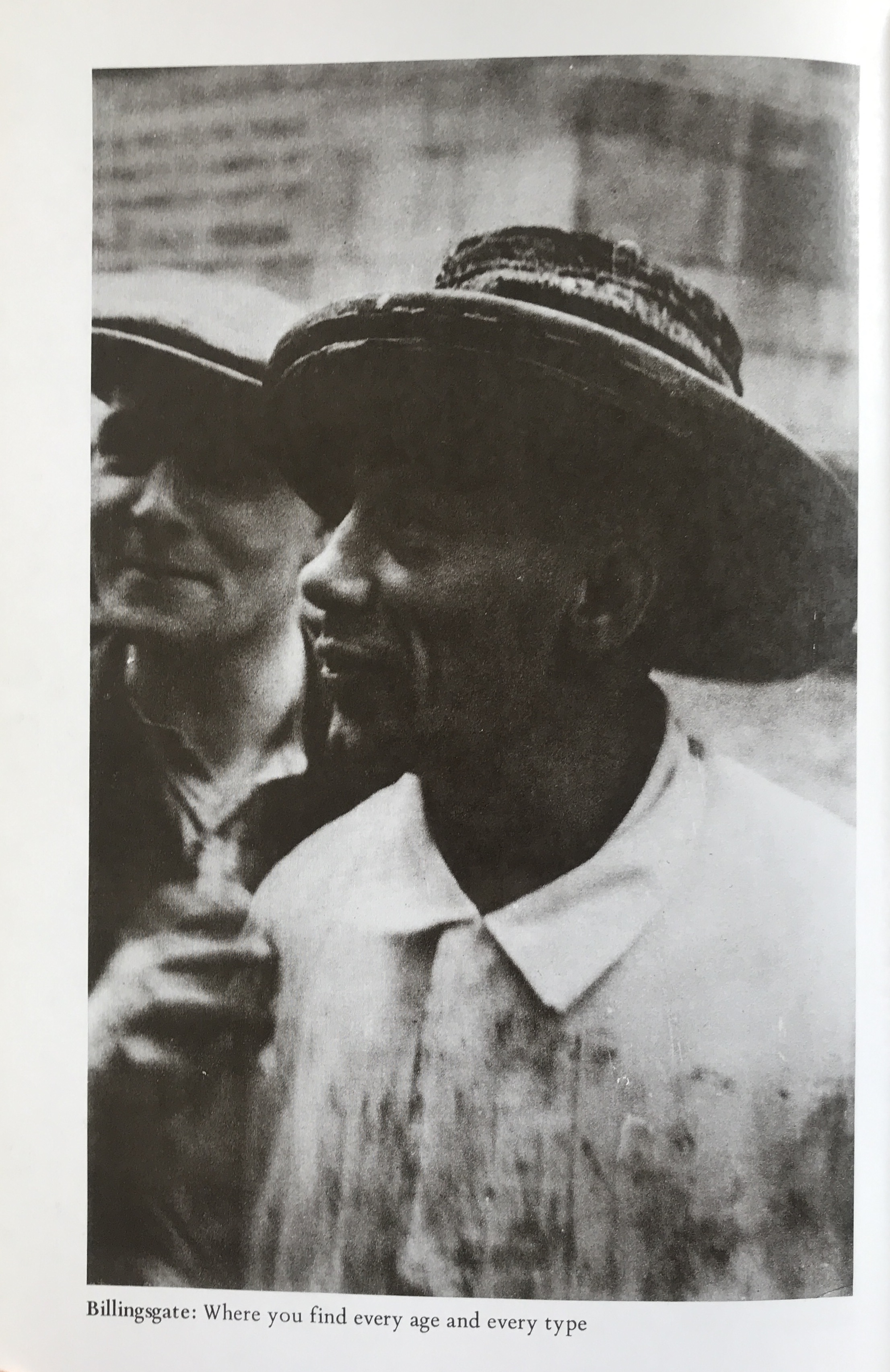

Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. Reissued 1972. Benjamin Blom, 1972, “Billingsgate: Where you find every age and every type” (Photo: Private Archive, © The Moholy-Nagy Foundation).

Anonymous. “London Street Markets.” The Observer, 20 September 1936, p. 9 (Photo: Private Archive).

J. B. “London’s Street Markets.” The Manchester Guardian, 23 October 1936, p. 6 (Photo: Private Archive). Anonymous. “London Street Markets.” The Observer, 20 September 1936, p. 9.

Benedetta, Mary. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. John Miles, 1936.

Benedetta, Mary. The Street Markets of London (reissued 1972). Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. Benjamin Blom, 1972.

Betjeman, John. An Oxford University Chest. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. John Miles, 1938.

Carullo, Valeria. Moholy-Nagy in Britain 1935–1937. Lund Humphries, 2019.

Fergusson, Bernard. Eton Portrait. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. John Miles, 1937.

J. B. “London’s Street Markets.” The Manchester Guardian, 23 October 1936, p. 6.

Moholy-Nagy, László. “Foreword.” Mary Benedetta. The Street Markets of London. Photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. John Miles, 1936, pp. vii–viii.

Senter, Terence. “Moholy-Nagy’s English Photography.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 123, no. 944, November 1981, pp. 659–671. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/880538. Accessed 9 March 2021.

Senter, Terence. “László Moholy-Nagy: The Transitional Years.” Albers and Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World, edited by Achim Borchardt-Hume, exh. cat. Tate Modern, London, 2006, pp. 85–91.

Word Count: 148

Word Count: 5

My deepest thanks go to Natalia Hug from The Moholy-Nagy Foundation for giving me permission to reproduce the works of László Moholy-Nagy.

Word Count: 23

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "The Street Markets of London." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5140-11260487, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

László Moholy-NagyPhotographerGraphic DesignerPainterSculptorLondon

László Moholy-Nagy emigrated to London in 1935, where he worked in close contact with the local avantgarde and was commissioned for window display decoration, photo books, advertising and film work.

Word Count: 30

A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939BookLondonSix years after her arrival in London, the photographer Lucia Moholy published her book A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939, on the occasion of the centenary of photography.

Word Count: 27