Archive

Studies in Hand-Reading

- Book

- Studies in Hand-Reading

Word Count: 3

- Charlotte Wolff

- 1936

- 1936

Chatto & Windus, 40–42 William IV Street, Charing Cross, London WC2.

- English

- London (GB)

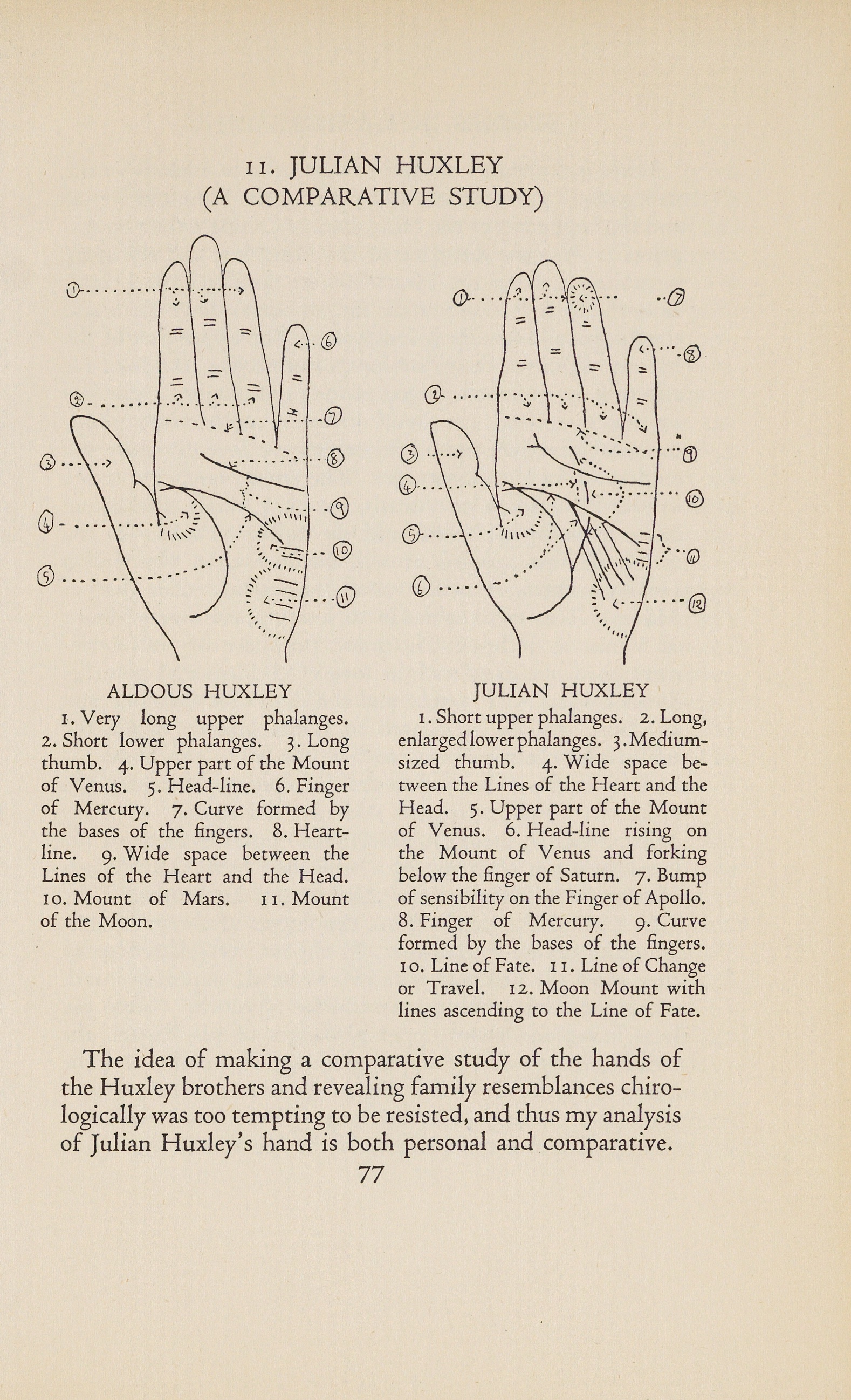

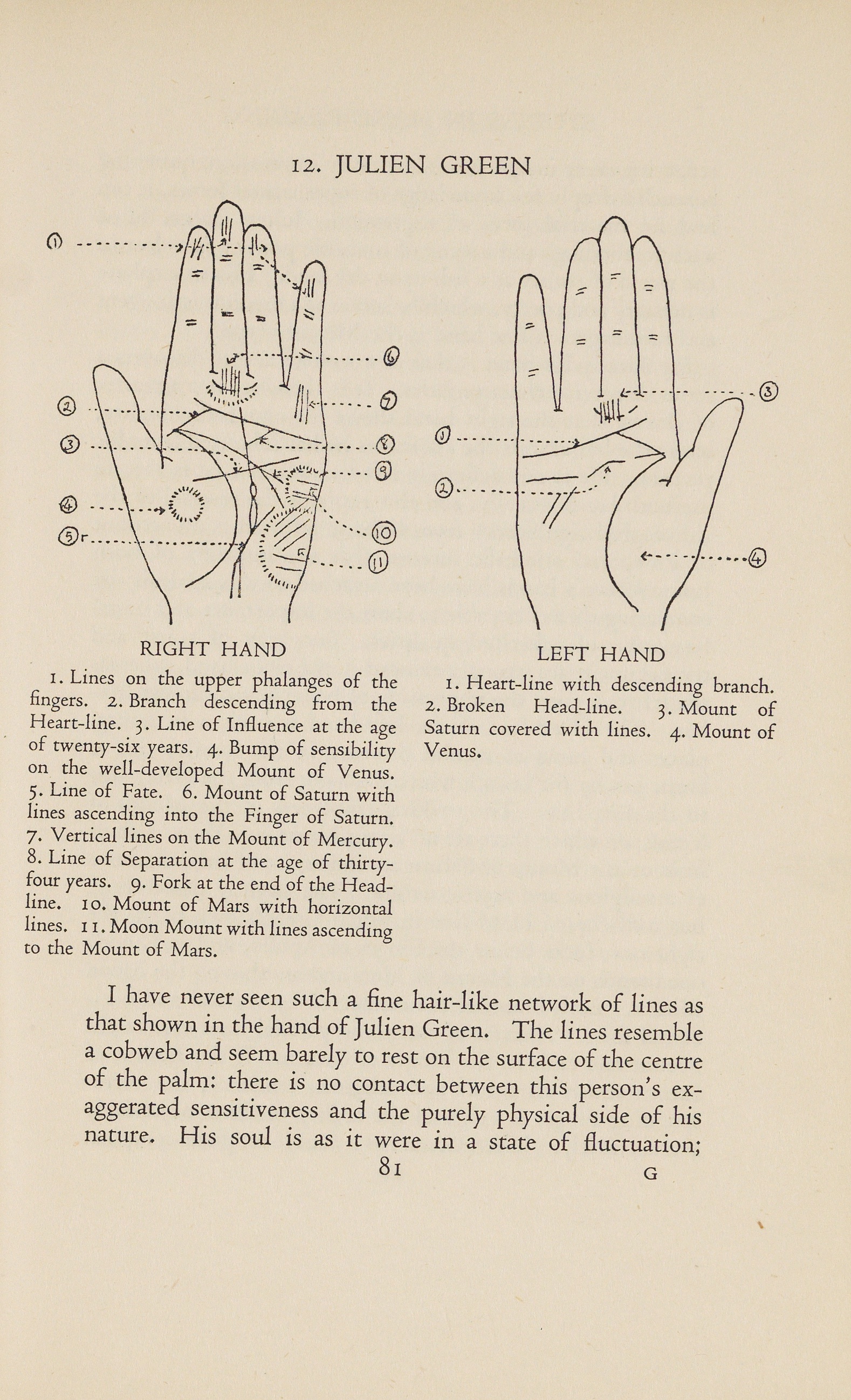

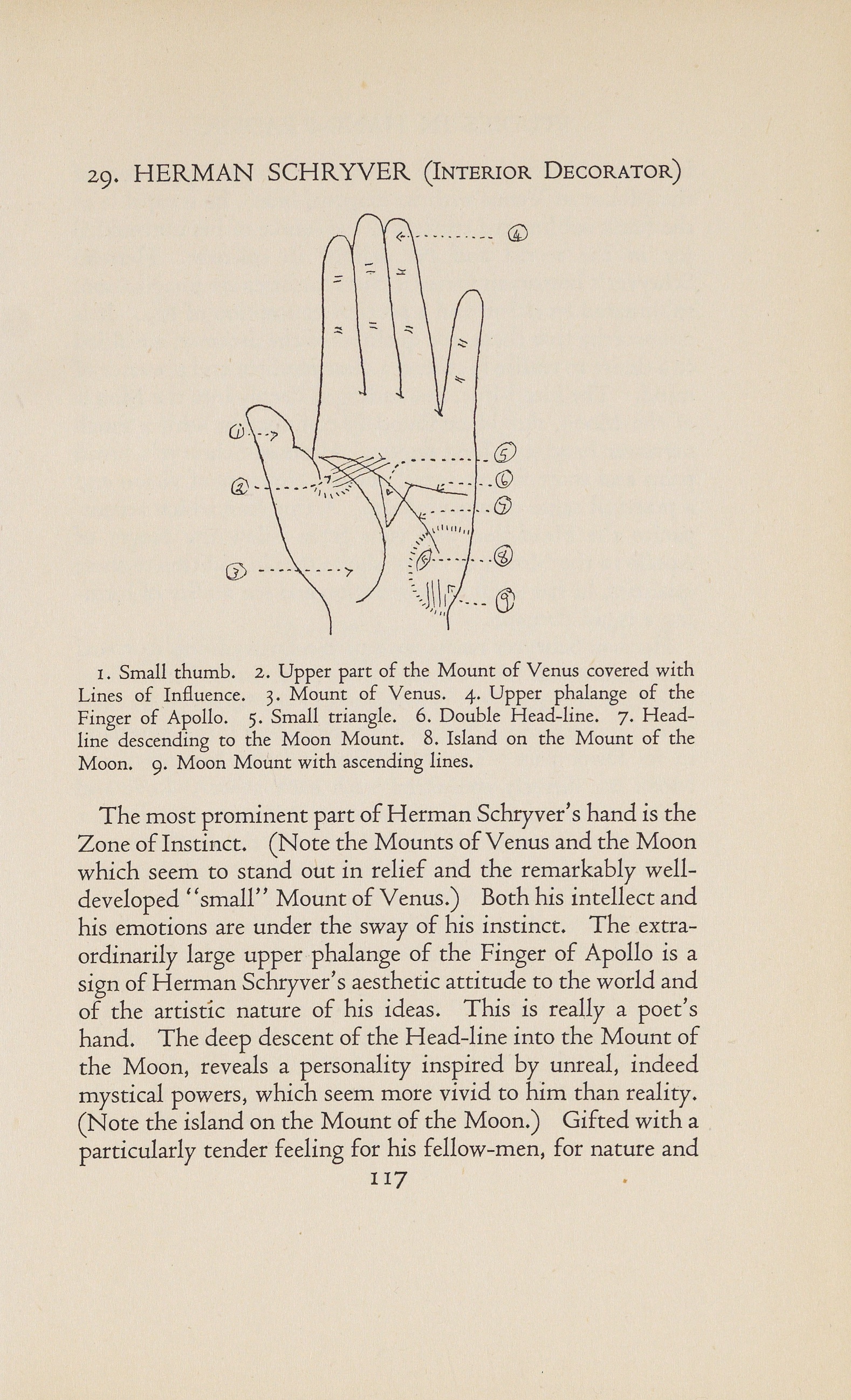

In 1936, Charlotte Wolff’s Studies in Hand-Reading was published with analysis of the palms of Horst P. Horst, Aldous and Julian Huxley, Man Ray and Virginia Woolf, among others.

Word Count: 29

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, p. 77: Julian Huxley (A Comparative Study): the hands of Aldous and Julian Huxley (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, bastard title (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, p. 81: Julien Green (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

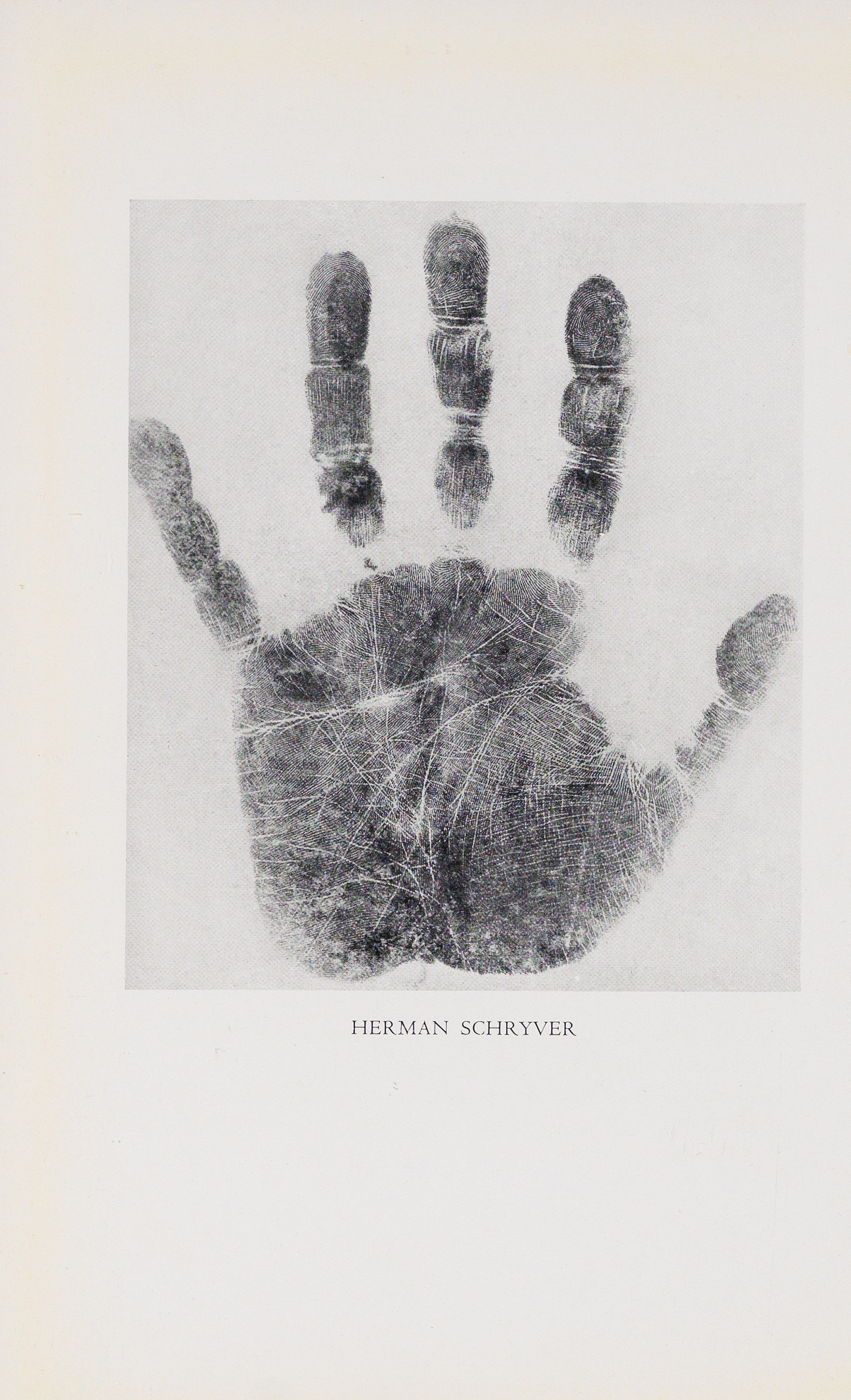

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, p. 117: Herman Schryver (Interior Decorator) (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, n.p.: hand of Herman Schryver (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

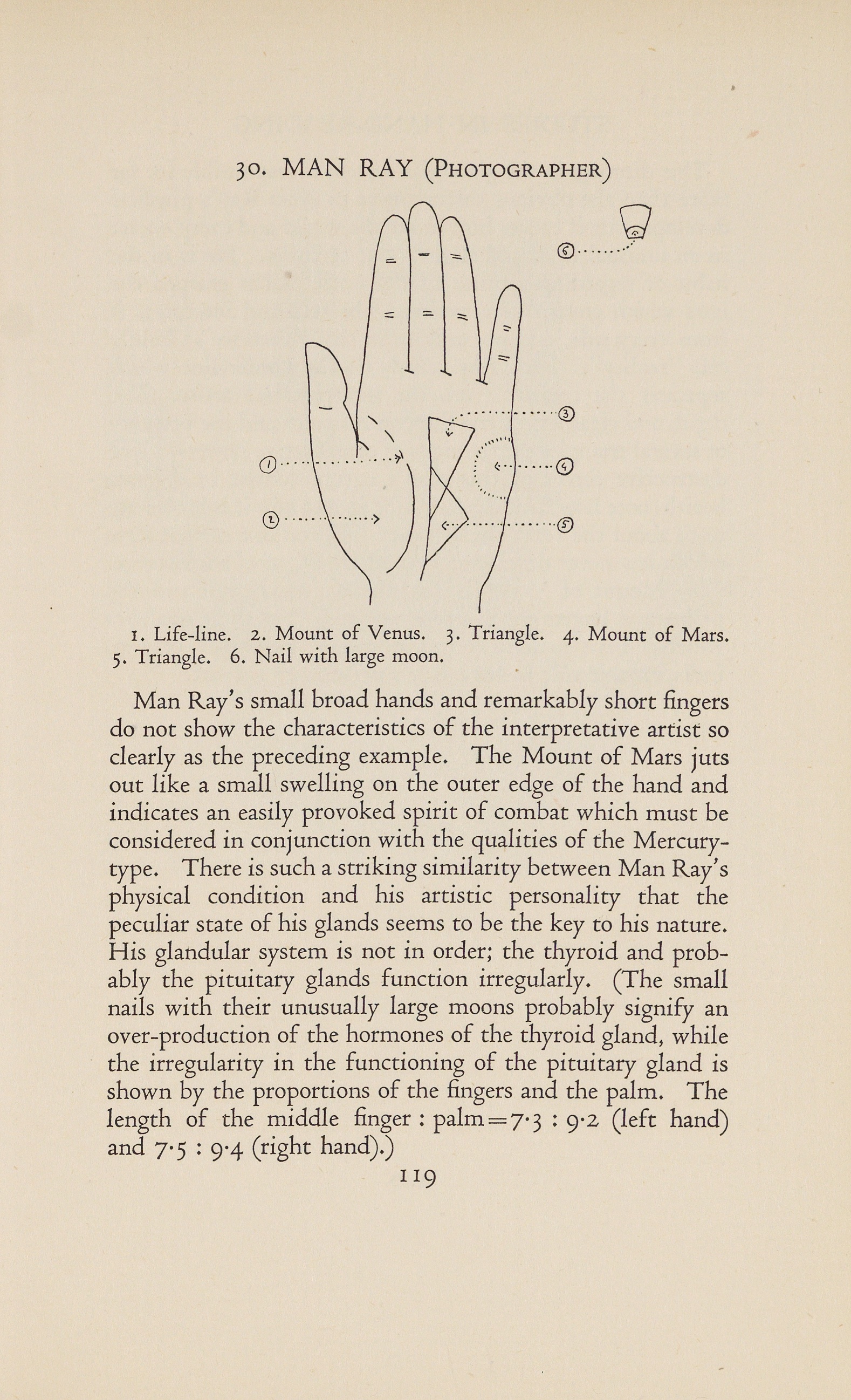

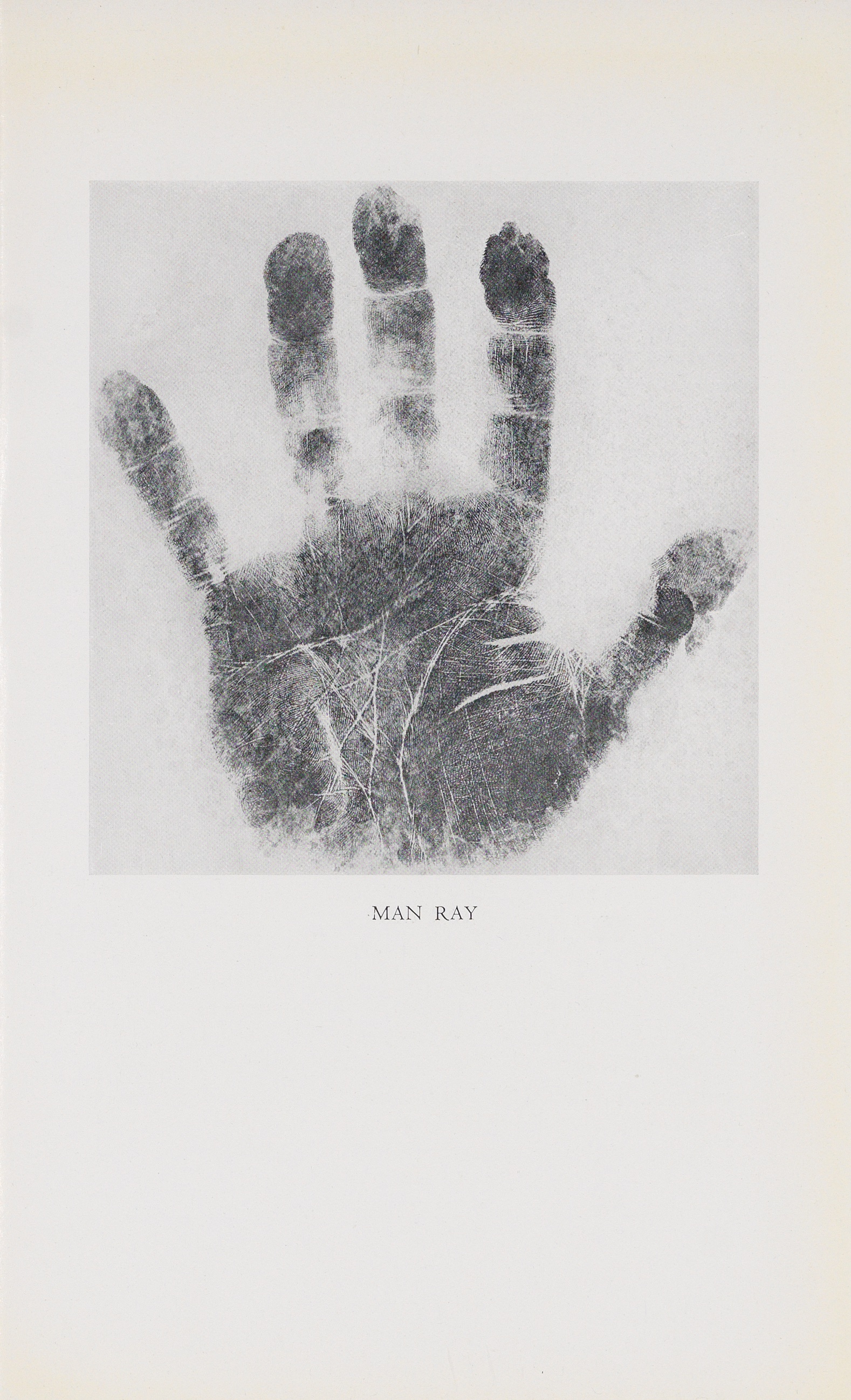

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, p. 119: Man Ray (Photographer) (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, n.p.: hand of Man Ray (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

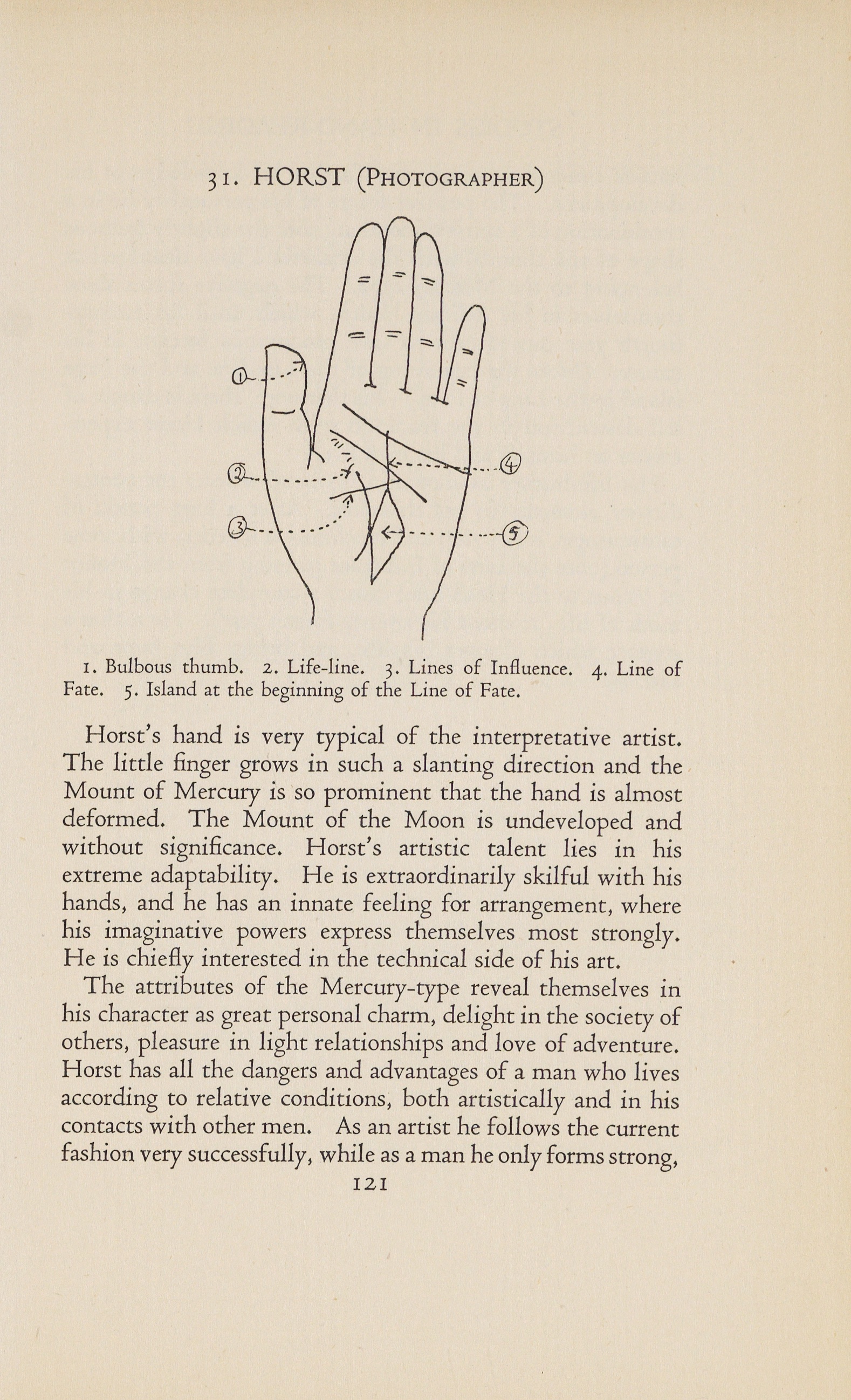

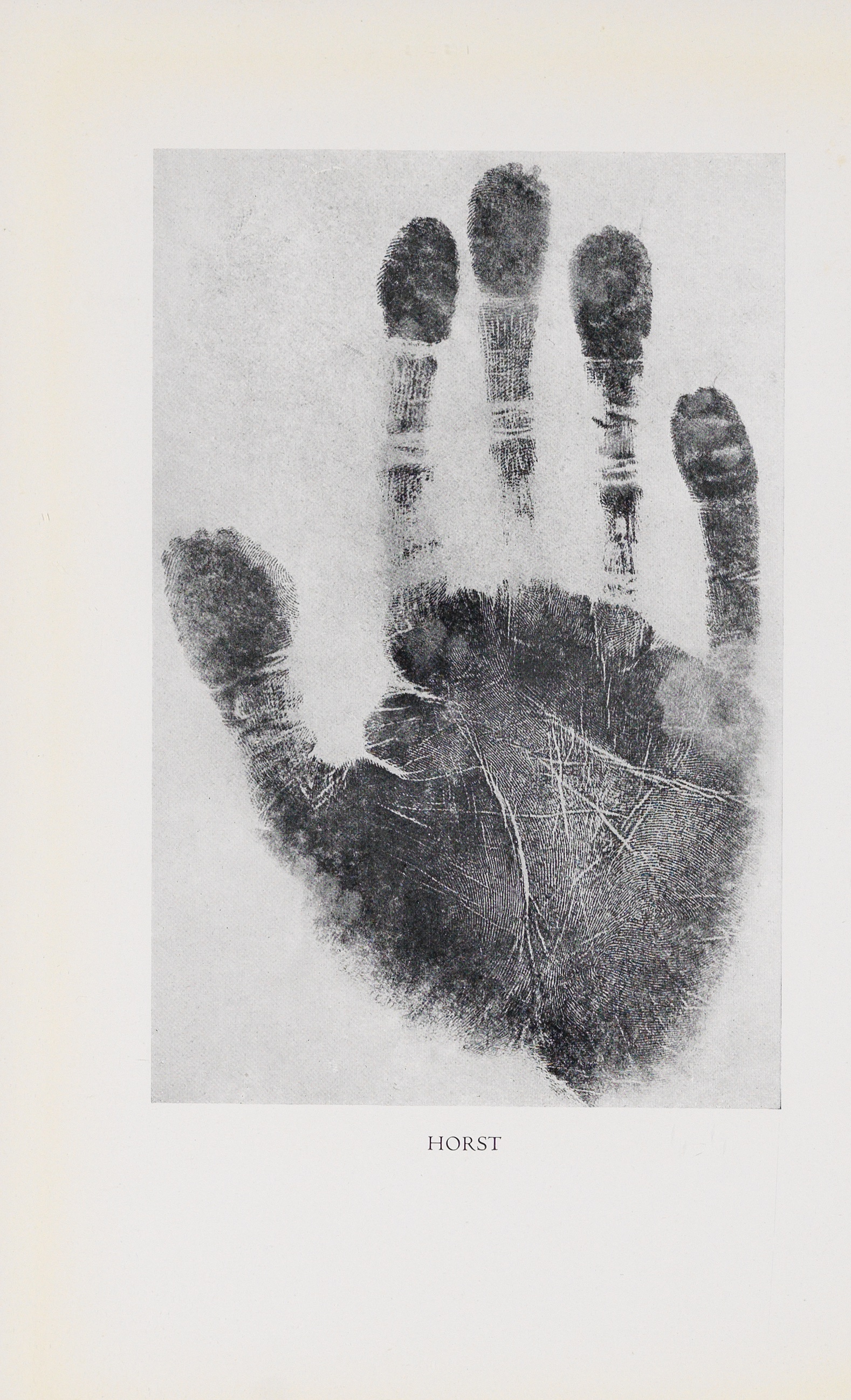

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, p. 121: Horst [P. Horst] (Photographer) (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

Charlotte Wolff. Studies in Hand-Reading. Chatto & Windus, 1936, n.p.: hand of Horst [P. Horst] (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main).

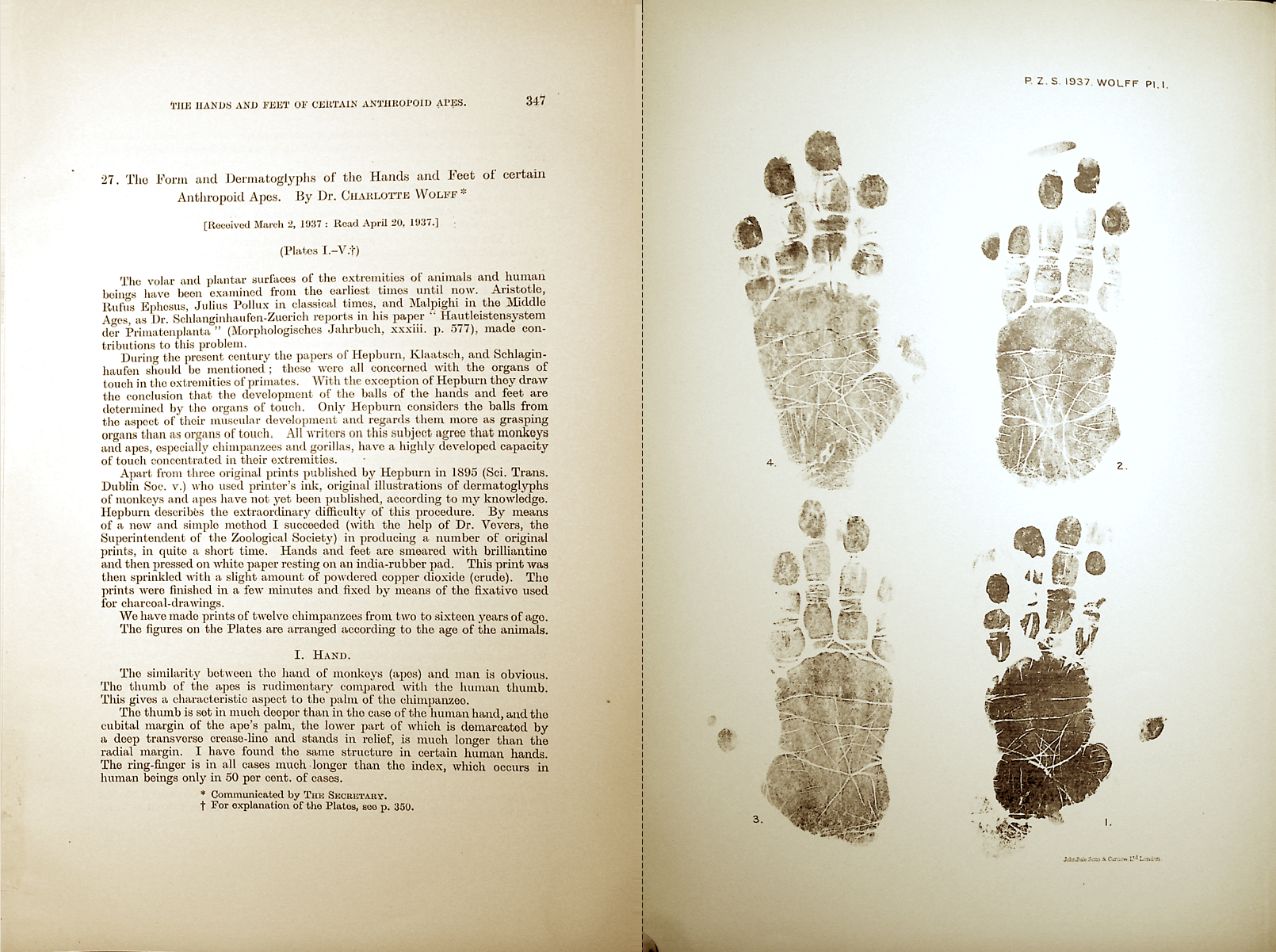

Charlotte Wolff. “The Form and Dermatoglyphs of the Hands and Feet of certain Anthropoid Apes”. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, Series A, 1937, Part 3, 347 + Plate (Library of the Zoological Institute, University of Hamburg). At the zoo’s behest, Charlotte Wolff applied chirology to the primates at London Zoo. Brennan, Toni Lee. Charlotte Wolff’s contribution to psychology and to the history of sexuality (doctoral thesis). University of Surrey, 2011. Surrey Research Insight Open Access, http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/id/eprint/843115. Accessed 25 March 2021.

Desideri, Valentina. Handreading Studies. Kunstverein Publishing, 2018.

Hawkey, Christian. “N Ear Flowers Re Fre/nd: A Poets’ Play.” Floor journal, no. 2, 10 October 2013, http://floorjournal.com/2013/10/10/n-ear-flowers-re-frend-a-poets-play/. Accessed 12 March 2021.

Rappold, Claudia. Charlotte Wolff (1897–1986). Ärztin, Psychotherapeutin, Wissenschaftlerin und Schriftstellerin. Hentrich und Hentrich, 2005.

Wolff, Charlotte. Studies in Hand-Reading. Translated by O.M. Cook, Chatto & Windus, 1936.

Wolff, Charlotte. “The Form and Dermatoglyphs of the Hands and Feet of certain Anthropoid Apes.” Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, vol. 107, Series A, Part 3, September 1937, pp. 347–350. ZSL, doi: doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1937.tb00816.x. Accessed 7 March 2021.

Wolff, Charlotte. “A Comparative Study of the Form and Dermatoglyphs of the Extremities

of Primates.” Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, vol. 108, Series A, Part 1, April 1938, pp. 143–161. ZSL, doi: doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1938.tb00025.x. Accessed 7 March 2021.Wolff, Charlotte. The Human Hand. Methuen, 1942.

Wolff, Charlotte. A Psychology of Gesture. Methuen, 1945.

Wolff, Charlotte. Love between Women. Gerald Duckworth, 1971.

Wolff, Charlotte. Bisexuality. A Study. Quartet, 1977.

Wolff, Charlotte. Augenblicke verändern uns mehr als die Zeit. Eine Autobiographie. Translated by Michaela Huber, Beltz Verlag, 1982.

Wolff, Charlotte. Magnus Hirschfeld. A Portrait of a Pioneer in Sexology. Quartet, 1986.

Word Count: 217

Word Count: 6

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Studies in Hand-Reading." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5140-11260535, last modified: 01-05-2021.

-

Julian HuxleyZoologistPhilosopherWriterLondon

Julian Huxley was the director of London Zoo from 1935 to 1942 and worked closely with emigrant photographers, artists and architects, including Berthold Lubetkin, Erna Pinner and Wolf Suschitzky.

Word Count: 27

Animal LanguageSound BookLondonIn 1938, the London publisher Country Life published the Animal Language sound book which featured text by Julian Huxley, audio records produced by Ludwig Koch and photographs by Ylla.

Word Count: 28