Archive

Die Zeitung

- Newspaper

- Die Zeitung

Word Count: 2

- 1941

- 1945

Maxwell Publishing, 107 Fleet Street, Holborn, London EC4.

- German

- London (GB)

From 1941 to 1945, the émigré German-language newspaper Die Zeitung was published in London, reporting on the war on the continent and on the situation in Germany.

Word Count: 25

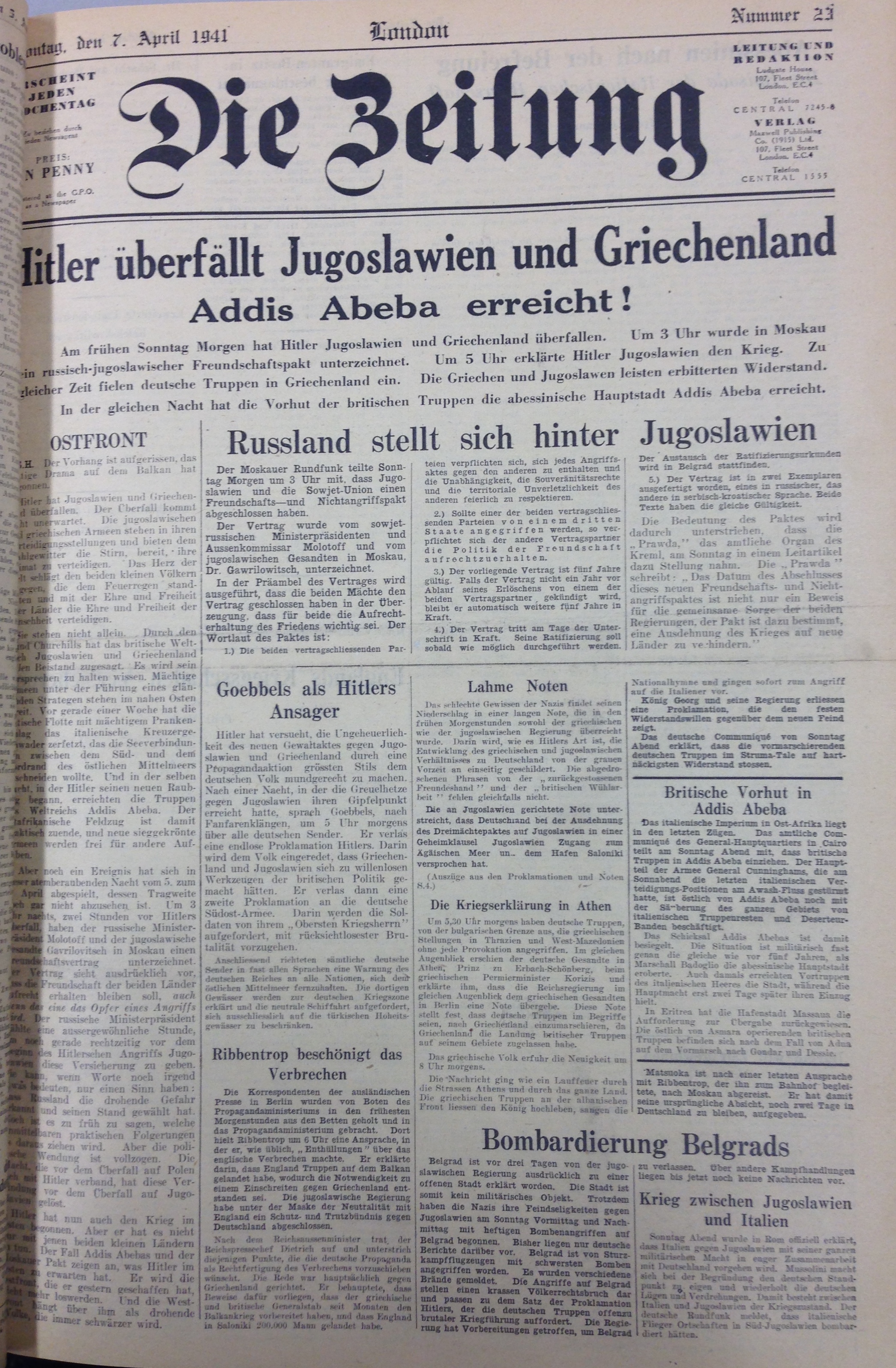

Front page of Die Zeitung, 7 April 1941 (Photo: Private Archive).

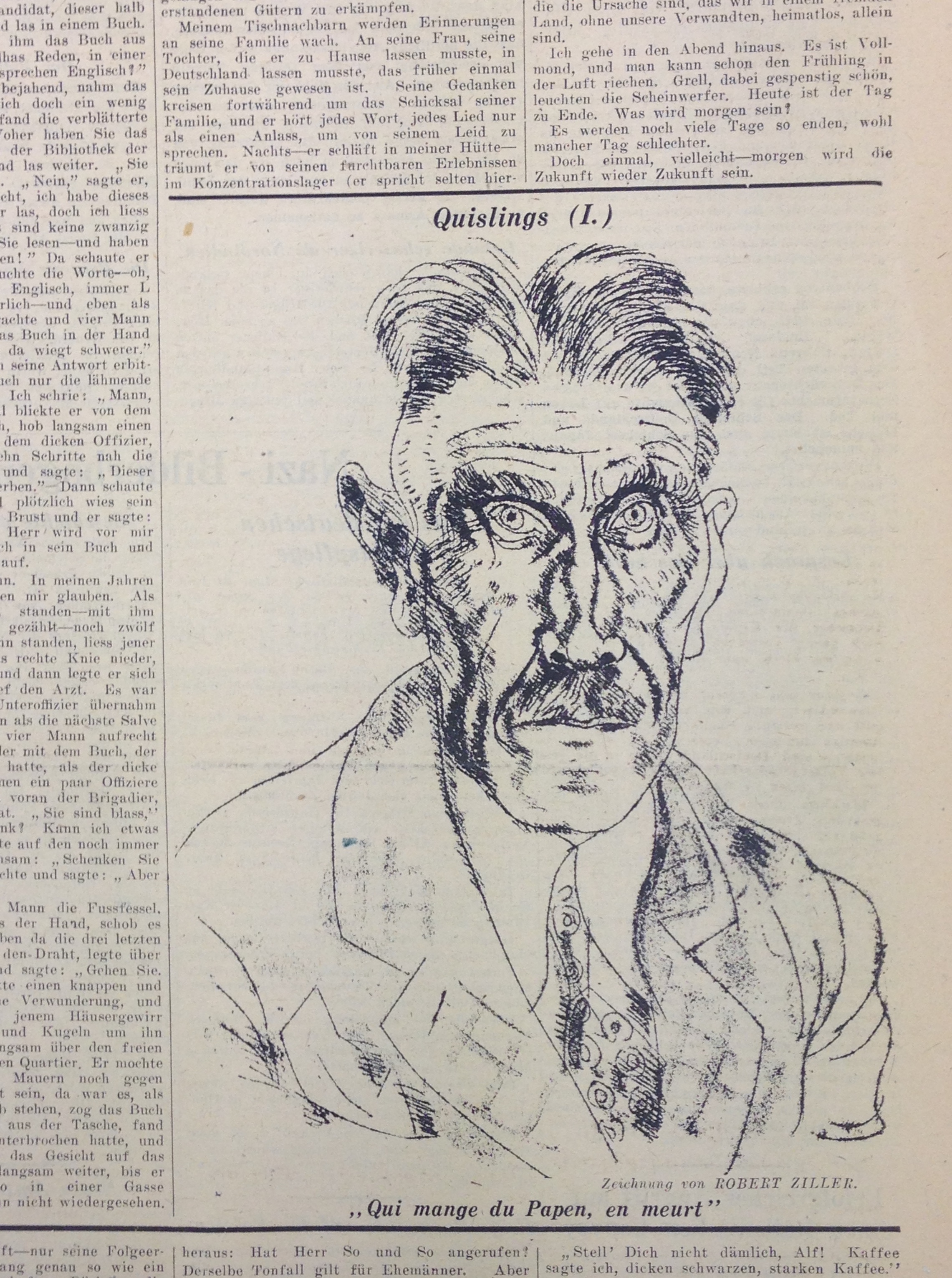

Robert Ziller [Richard Ziegler], Quislings (I.): “Qui mange du Papen, en meurt", in Die Zeitung, 29 March 1941, p. 3 (© Richard Ziegler).

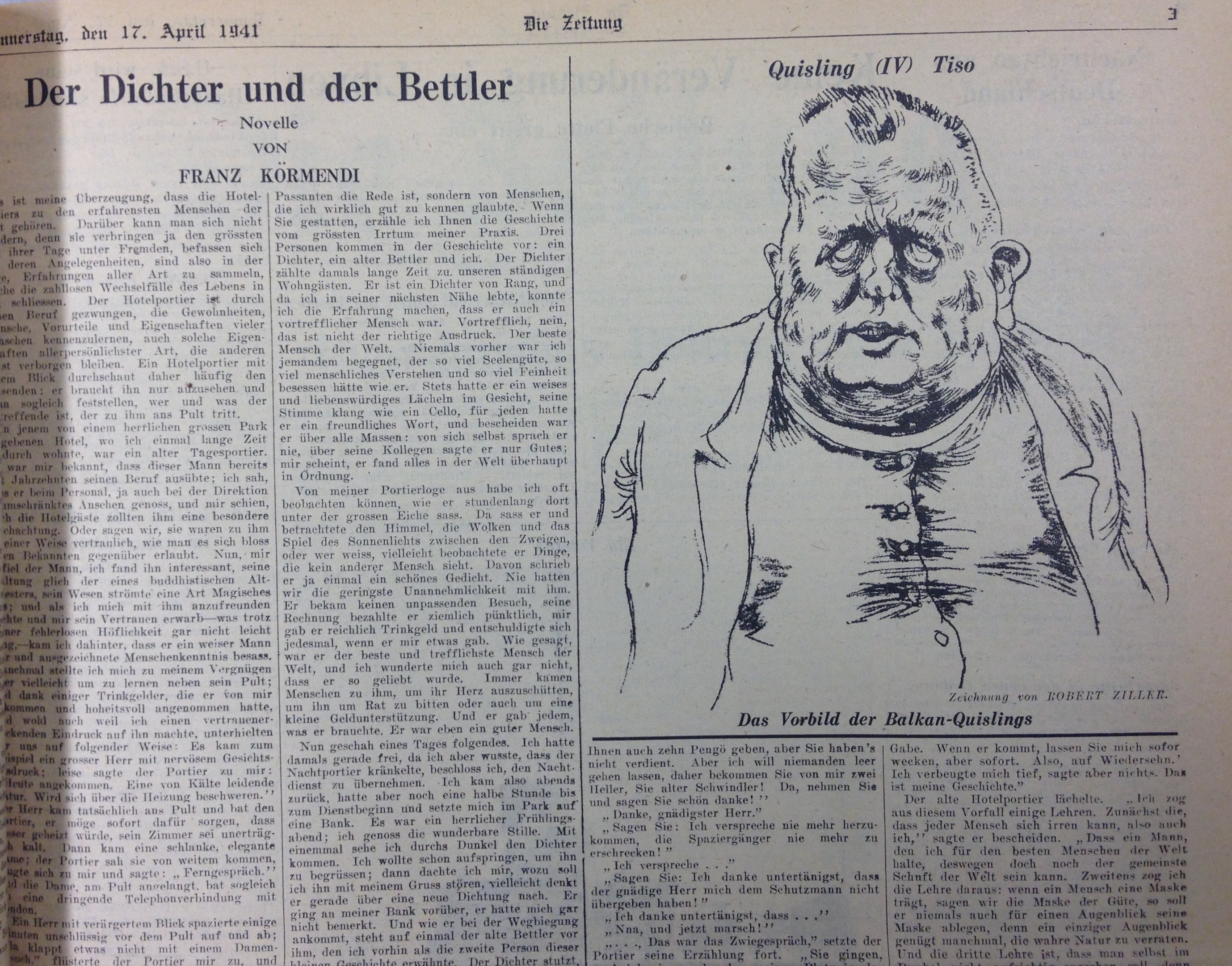

Robert Ziller [Richard Ziegler], Quislings (IV.) Tiso: Das Vorbild des Balkan-Quislings [Model of the Balkan Quisling], in Die Zeitung, 17 April 1941, p. 3 (© Richard Ziegler).

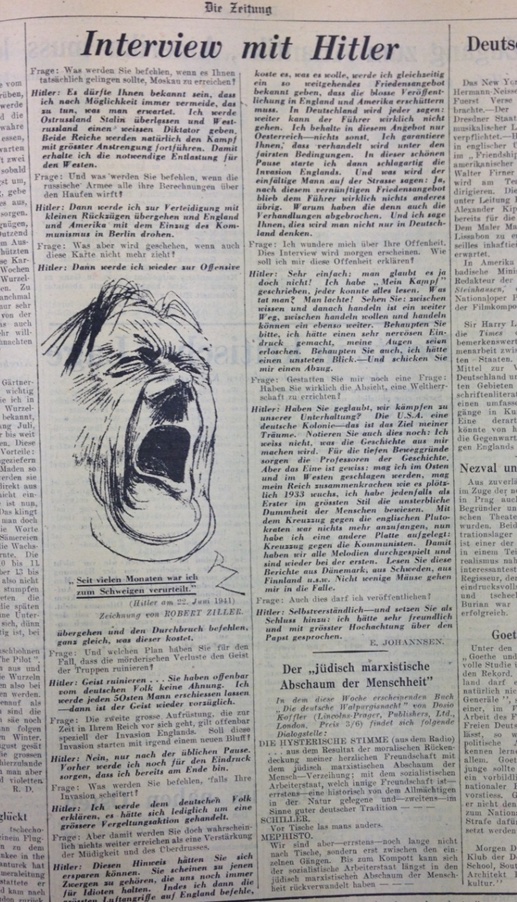

Robert Ziller [Richard Ziegler], “Seit vielen Monaten war ich zum Schweigen verurteilt” [For many months I had been condemned to silence], in Die Zeitung, 2 July 1941, p. 3 (© Richard Ziegler).

Robert Ziller [Richard Ziegler], B.D.M., in Die Zeitung, 8 July 1941, p. 3 (© Richard Ziegler).

Robert Ziller [Richard Ziegler], Mussolini, in Die Zeitung, 6 August 1941, p. 3 (© Richard Ziegler).

Robert Ziller [Richard Ziegler], Heinrich Himmler, in Die Zeitung, 27 October 1944, p. 4 (© Richard Ziegler).

Walter Trier, Des Führers Ahnengalerie [The Führer’s Ancestral Gallery] in Die Zeitung, 3 September 1941, p. 3 (Photo: Private Archive).

Walter Trier, Der Führer: “Komm nur weiter, wir sind sicher bald oben!” [Keep coming, I’m sure we’ll be up there soon!] in Die Zeitung, 22 September 1941, p. 3 (Photo: Private Archive).

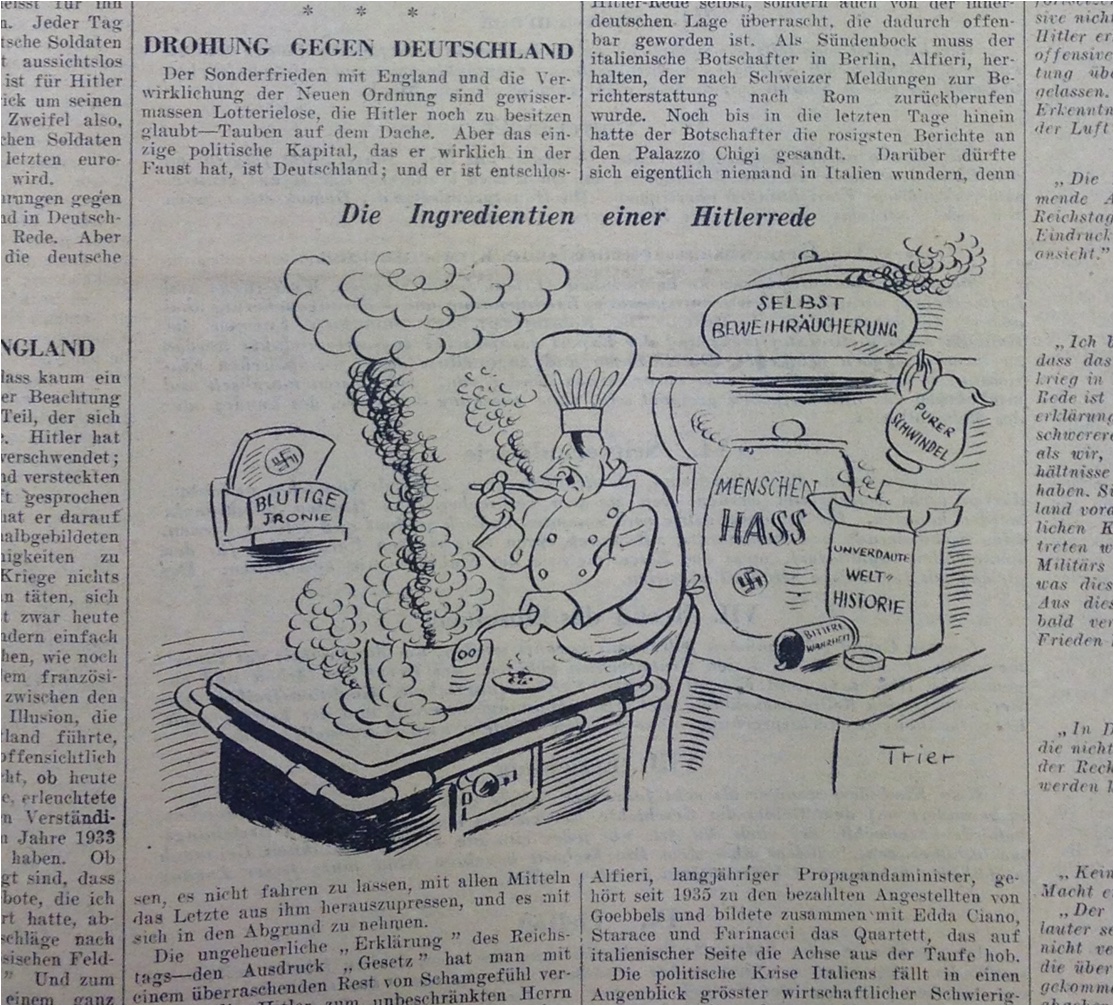

Walter Trier, Die Ingredientien einer Hitlerrede [The Ingredients of a Hitler Speech], in Die Zeitung, 3 January 1942, p. 3 (Photo: Private Archive).

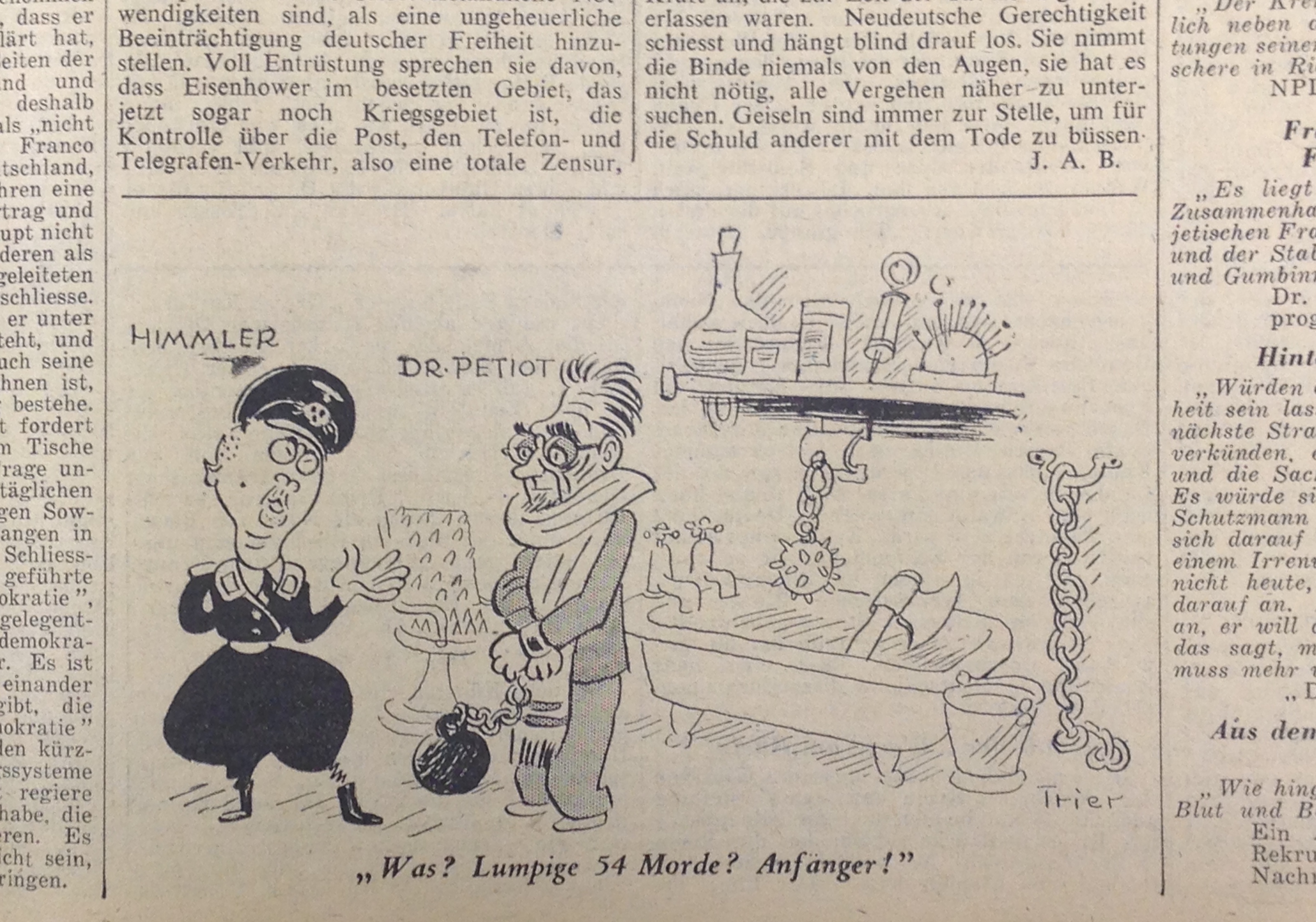

Walter Trier, Himmler, Dr. Petiot: “Was? Lumpige 54 Morde? Anfänger!” [What? A measly 54 murders? Rookie!] in Die Zeitung, 3 January 1942, p. 3 (Photo: Private Archive). Walter Trier’s final illustration for Die Zeitung, dedicated to a fictional conversation between a serial killer (Petiot) and a mass murderer (Himmler). Dogramaci, Burcu. “Der Stift als Seziermesser im englischen Exil. Politische Zeichnungen von Richard Ziegler und Walter Trier für Die Zeitung.” Exil im Krieg (1939–1945), edited by Hiltrud Häntzschel et al., V&R, 2016, pp. 99–110.

Greiser, Gerd. “Exilpublizistik in Großbritannien.” Presse im Exil. Beiträge zur Kommunikationsgeschichte des deutschen Exils 1933–1945 (Dortmunder Beiträge zur Zeitungsforschung, 30), edited by Hanno Hardt et al., KG Saur, 1979, pp. 223–253.

Haffner, Sebastian. Geschichte eines Deutschen. Die Erinnerungen 1914–1933. Als Engländer maskiert. Ein Gespräch mit Jutta Krug über das Exil. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2006.

Hartig, Christine. “Einwanderungsrecht und die Konstruktion von Geschlechterrollen. Die Situation von jüdischen Flüchtlingen in Großbritannien und den USA im Vergleich.” Doing Gender in Exile. Geschlechterverhältnisse, Konstruktionen und Netzwerke in Bewegung, edited by Irene Messinger and Katharina Prager, Westfälisches Dampfboot, 2019, pp. 95–109.

Hiepe, Richard. “Deutschland ist erwacht. Die antifaschistischen Zeichnungen von Richard Ziegler.” Sammlung. Jahrbuch für antifaschistische Literatur und Kunst, vol. 2, edited by Uwe Naumann, Röderberg, 1979, pp. 80–87.

Hofmann, Karl-Ludwig. “Zur Geschichte der deutschen antifaschistischen Pressesatire.” Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 1986, pp. 65–72.

Humorist Walter Trier. Selections from the Trier-Fodor Foundation Gift, exh. cat. Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario, 1980.

Krejsa, Michael. “NS-Reaktionen auf Heartfields Arbeit 1933–1939.” John Heartfield, exh. cat. Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 1991, pp. 368–377.

Low, David. “Preface.” Jesters in Earnest. Cartoons by the czechoslovak Artists Z.K. – A. Hoffmeister – A. Pelc – Stephen – W. Trier, John Murray, 1944, n.p.

Neuner-Warthorst, Antje. Walter Trier. Eine Bilderbuch-Karriere. Nicolai, 2014.

Tergit, Gabriele. “Die Exilsituation in England.” Die deutsche Exilliteratur 1933–1945, edited by Manfred Durzak, Reclam, 1973, pp. 135–144.

Word Count: 261

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Die Zeitung." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5140-8103272, last modified: 21-06-2021.

-

John HeartfieldArtistGraphic DesignerFotomonteur (mounter of photographs)London

After escaping from his first exile in Prague in December 1938, the political artist John Heartfield lived in London since 1950, working for Picture Post and the publisher Lindsay Drummond.

Word Count: 28

Wolf SuschitzkyPhotographerCinematographerLondonThe Viennese Wolf Suschitzky made a career as a photographer and cinematographer after emigrating to London in 1935.

Word Count: 17

We make HistoryBookLondonIn 1940, émigré artist Richard Ziegler, using the pseudonym Robert Ziller, published the book We Make History with the Allen & Unwin publishing house in London.

Word Count: 25

LilliputMagazineLondonThe magazine Lilliput, founded by the émigré journalist Stefan Lorant in 1937, gave work to emigrated artists and photographers such as Kurt Hutton, Walter Suschitzky, Walter Trier and Edith Tudor-Hart.

Word Count: 29

Visual Pleasures from Everyday ThingsBookletLondonVisual Pleasures from Everyday Things is a booklet written in 1946 by the emigrated architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner with the aim of aesthetic education and teacher training.

Word Count: 26

Black Star Publishing Company LondonPhoto AgencyLondonThe 1936 New York-founded Black Star Publishing Company photo agency opened a European branch in London the same year in response to the high demand for foreign images in the U.S.

Word Count: 31

Lindsay DrummondPublishing HouseLondonThe artist John Heartfield designed covers for the publishing house Lindsay Drummond, which had an anti-fascist programme and published books by emigrated authors such as Wilhelm Necker and Felix Langer.

Word Count: 30

The Warburg InstituteResearch InstituteLondonThe Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in Hamburg achieved a new presence in London after 1933 under the name The Warburg Institute as a research institution with a library and photo archive.

Word Count: 29