Archive

Allies inside Germany

- Allies inside Germany

Word Count: 3

- Exhibition

- 03-07-1942

- 16-08-1942

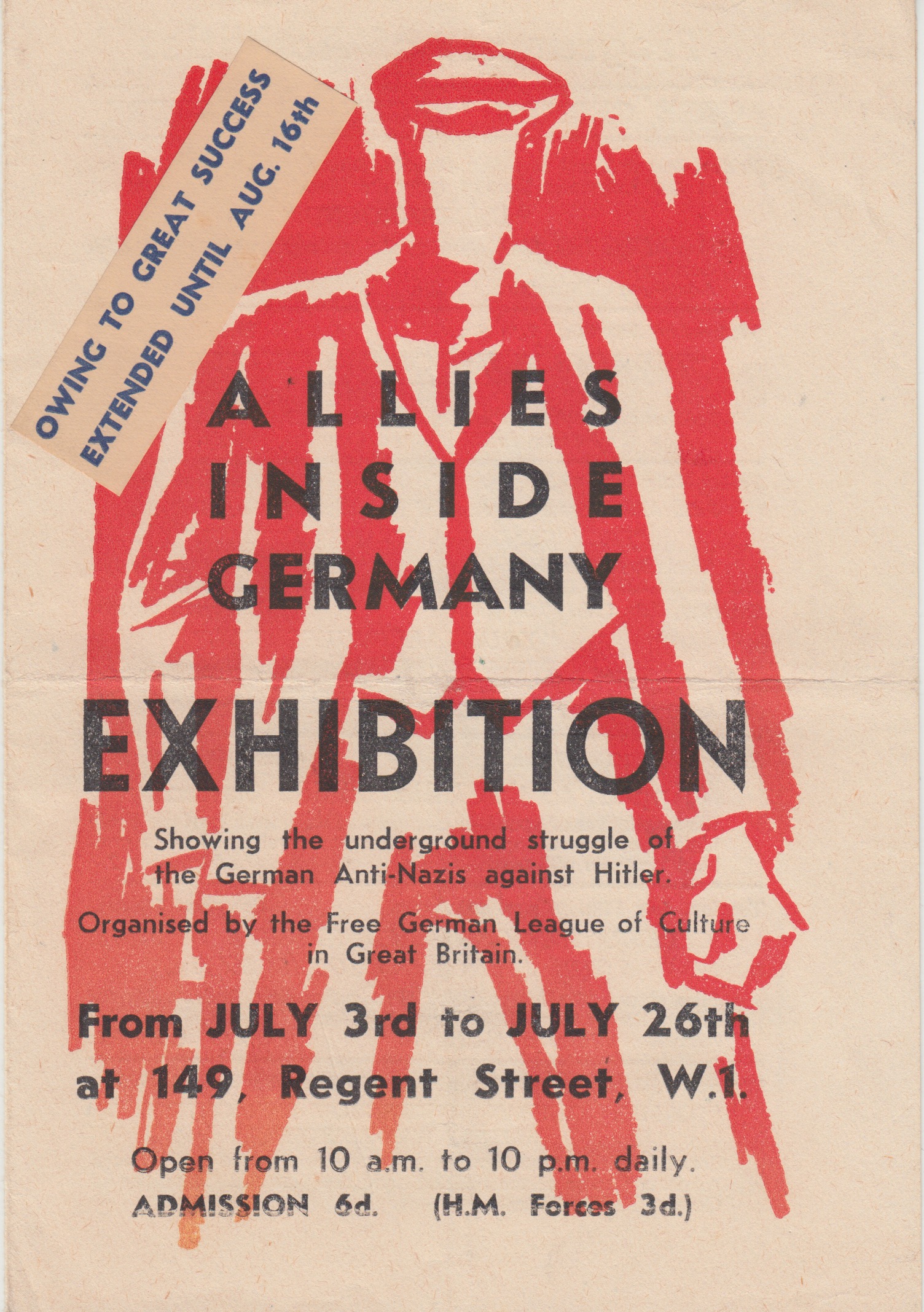

On 3 July 1942, the Allies inside Germany exhibition, organised by the Free German League of Culture, opened in London in an empty shop at 149 Regent Street.

Word Count: 25

Allies inside Germany, leaflet, cover, 1942, design by René Graetz (METROMOD Archive).

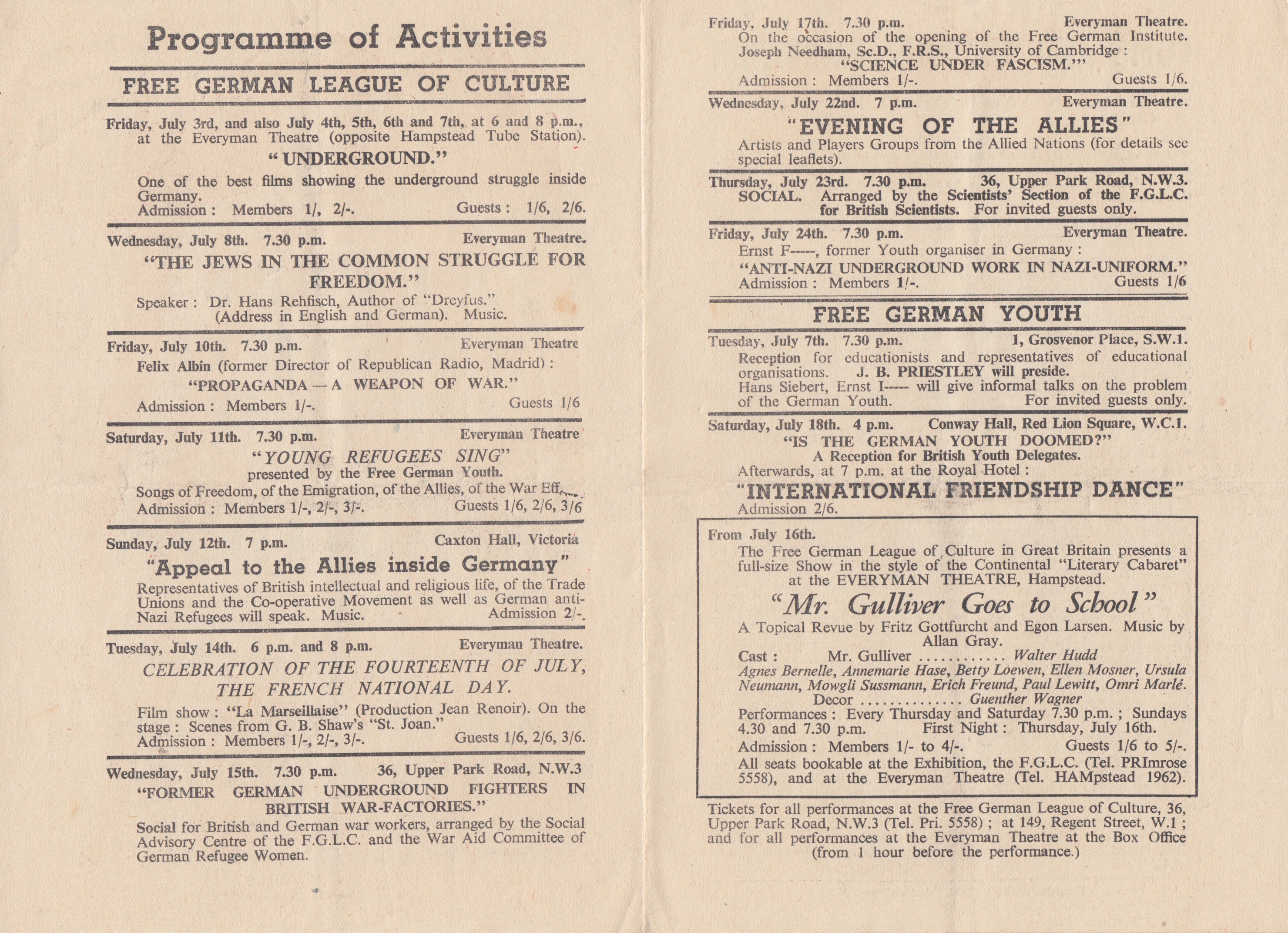

Allies inside Germany, leaflet, pp. 2–3: Programme of Activities, 1942 (METROMOD Archive).

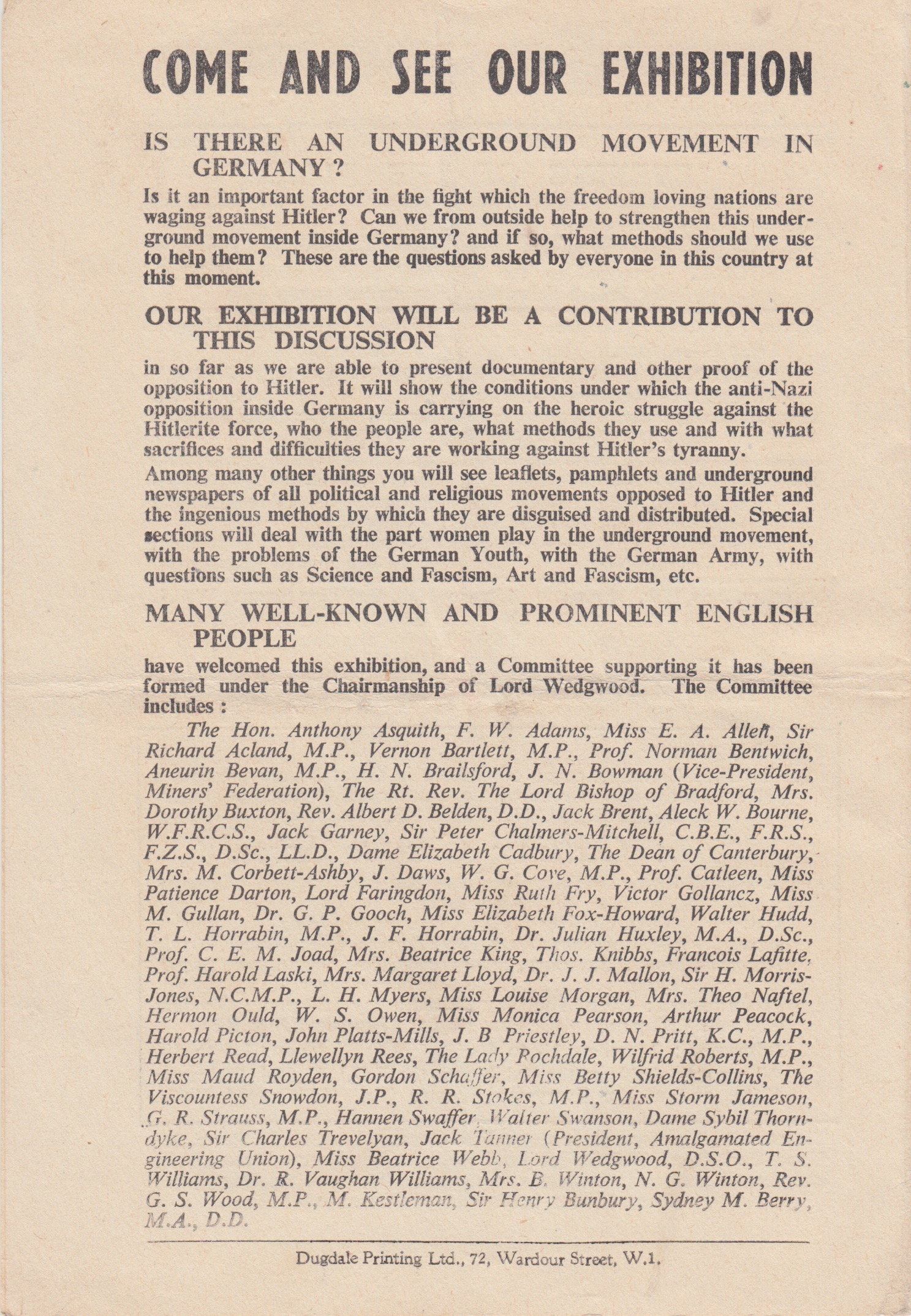

Allies inside Germany, leaflet, p. 4: Come and see our exhibition, 1942 (METROMOD Archive).

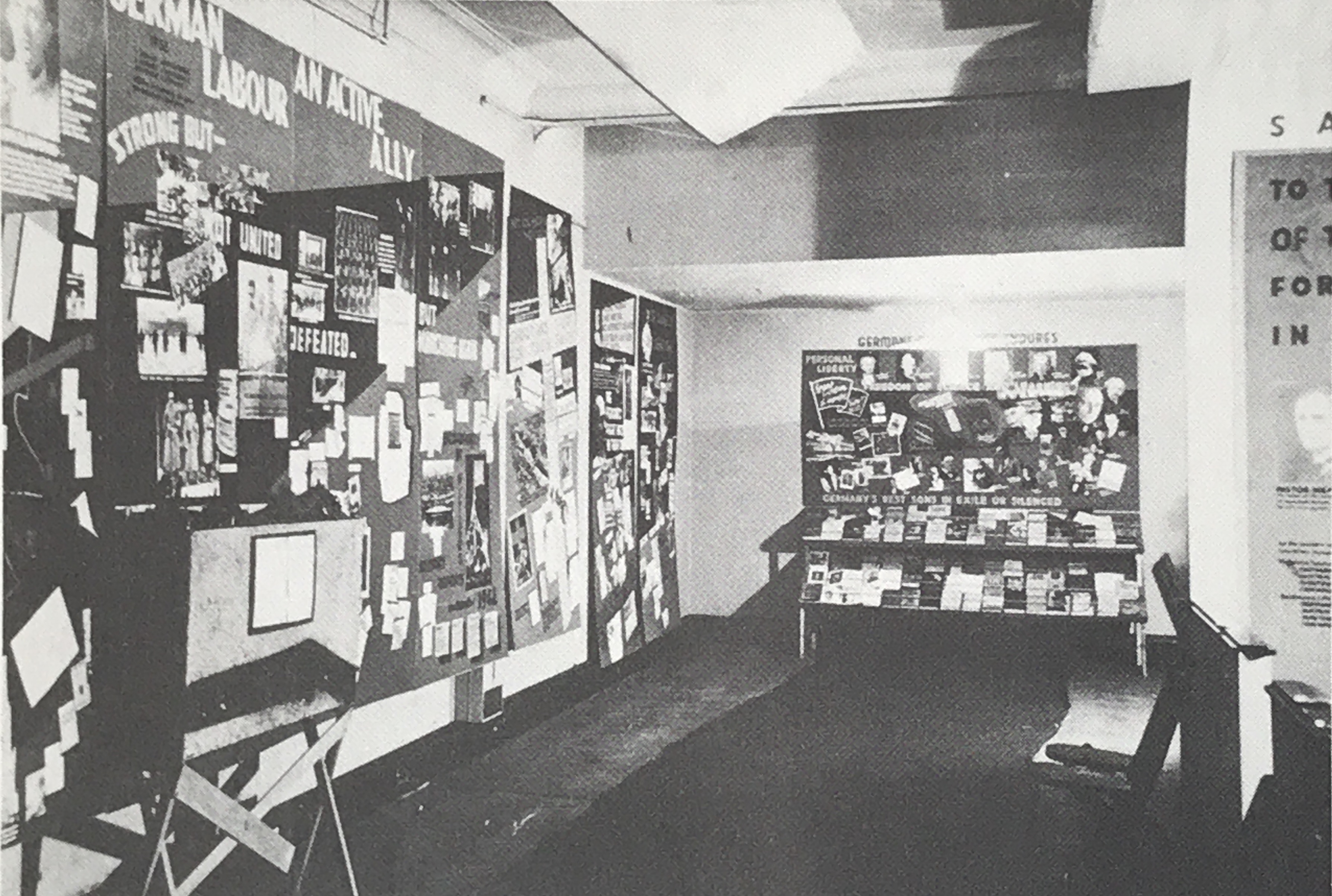

Allies inside Germany, exhibition view, shop at 149 Regent Street, 1942 (Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1986, 44).

Allies inside Germany, panel: “1933 – Hitler comes to Power”, 1942 (Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1986, 41).

Allies inside Germany, panel: “1934 – In Power”, 1942. Photomontage 30. Juni 1934: Heil Hitler! (1934) by John Heartfield (Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1986, 41, © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021).

Allies inside Germany, panel: “22 June 1941 – One by One”, 1942 (Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1986, 42).

Allies inside Germany, panel: “Second Front – Victory 1942”, 1942. 5 Minutes to 12 photomontage, (1942) by John Heartfield (Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1986, 43, © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021).

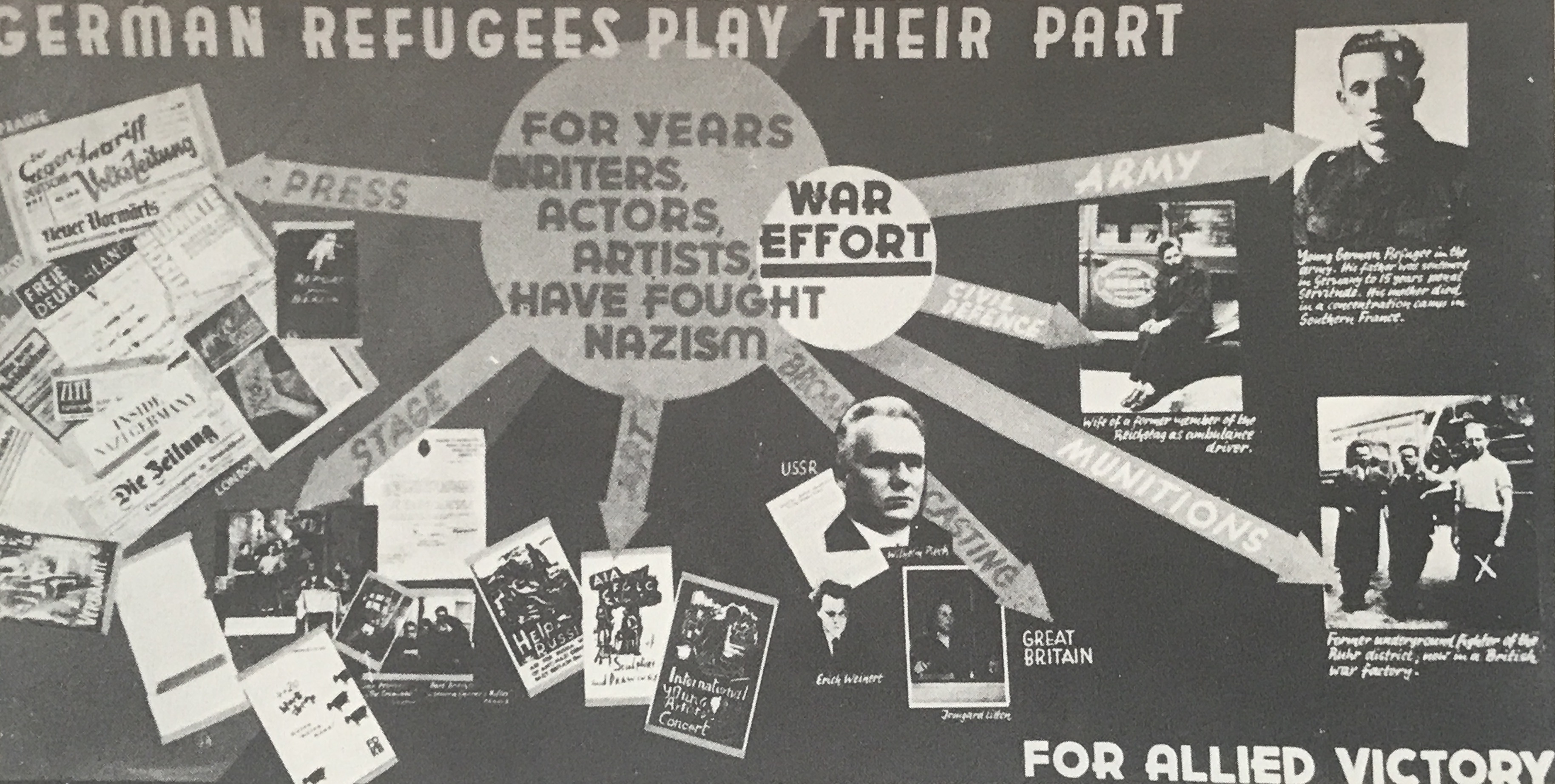

Allies inside Germany, panel: “German Refugees Play Their Part for Allied Victory”, 1942 (Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1986, 44).

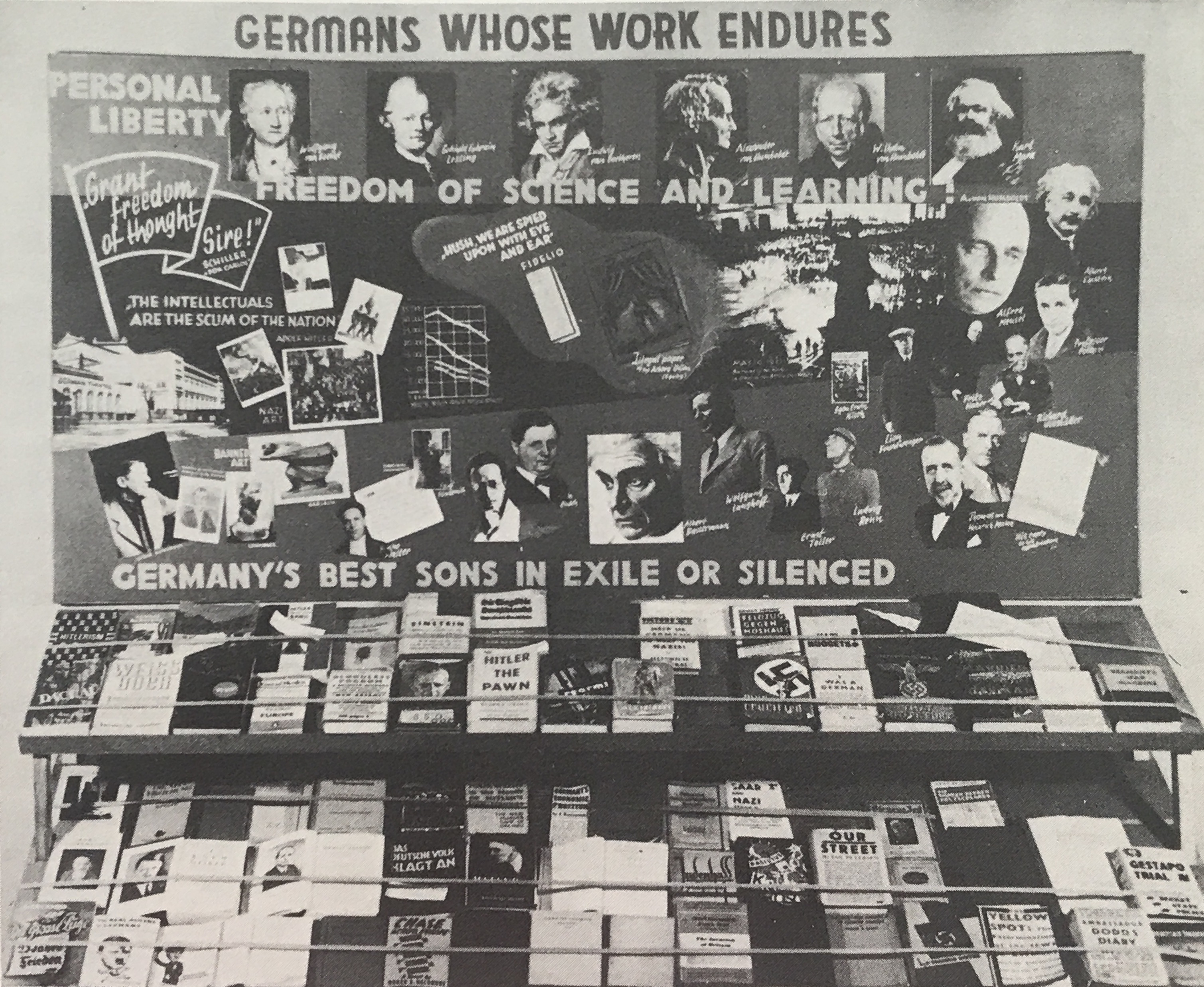

Allies inside Germany, panel: “Germans whose work endures”, 1942 (Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1986, 43).

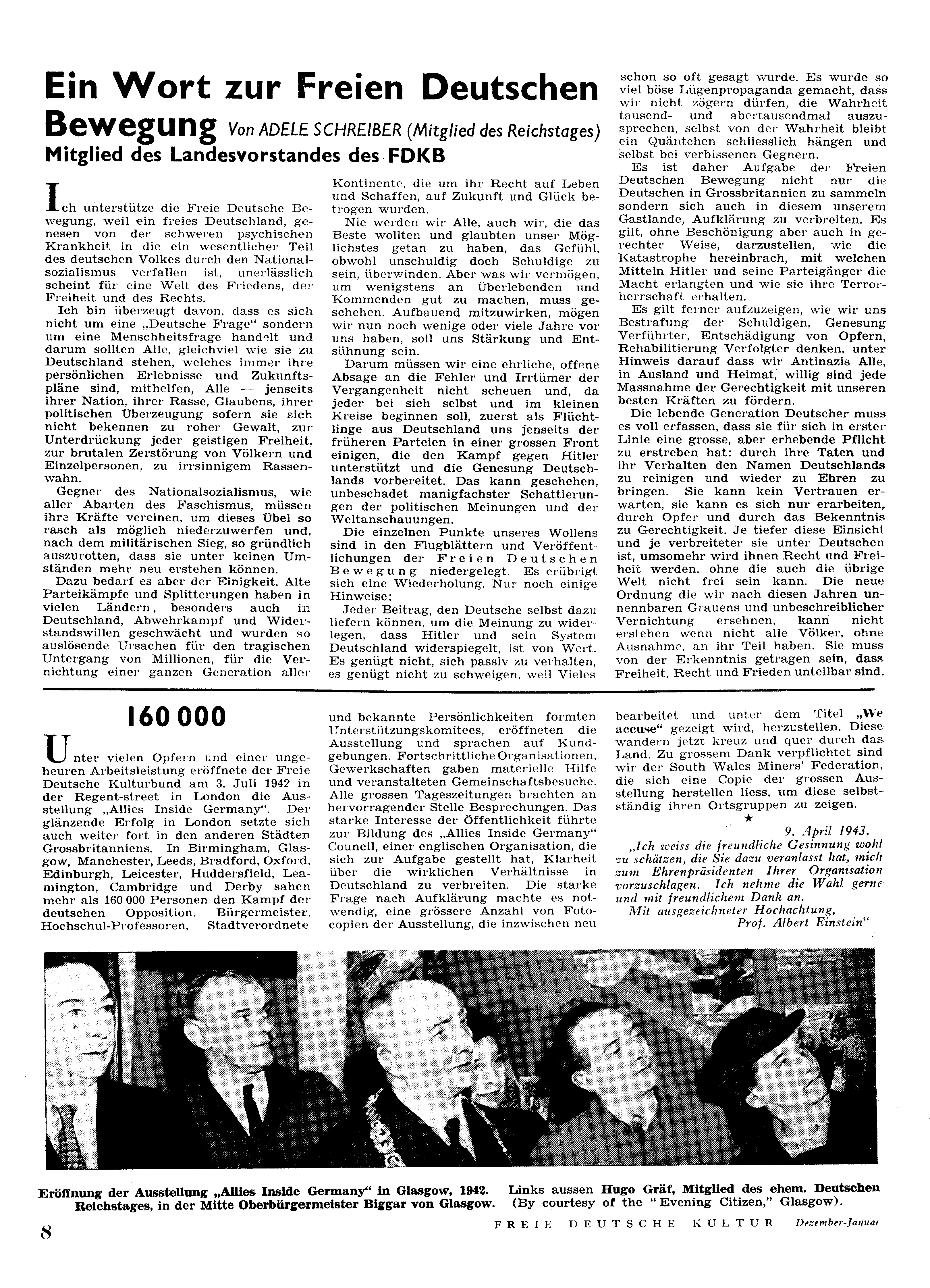

Allies inside Germany on tour: opening ceremony in Glasgow, 1942, in Freie Deutsche Kultur, no. 12, 1943, p. 8 (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main). Bihler, Lori Gemeiner. Cities of refuge: German Jews in London and New York, 1935–1945. SUNY Press, 2018.

Chadour-Sampson, Anna Beatriz. “Barbara Cartlidge. Life and Work.” Barbara Cartlidge and Electrum Gallery. A Passion for Jewellery, edited by Anna Beatriz Chadour-Sampson and Janice Hosegood, arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2016, pp. 12–85.

Coles, Anthony. John Heartfield. Ein politisches Leben. Böhlau, 2014.

Frowein, Cordula. “Ausstellungsaktivitäten der Exilkünstler.” Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, Frölich & Kaufmann, 1986, pp. 35–48.

Kokoschka, Oskar, President of Free German League of Culture. Letter (Akademie der Künste, Archiv Bildende Kunst, 9 April 1942).

Müller-Härlin, Anna. “The Artists’ Section.” Politics By Other Means. The Free German League of Culture in London 1939–1946, edited by Charmian Brinson and Richard Dove, Vallentine Mitchell, 2010, pp. 54–73.

Schultz, Anna. “John Heartfield. A Political Artist’s Exile in London.” Burning Bright. Essays in the Honour of David Bindman, edited by Kim Sloan, UCL Press, 2015, pp. 253–263.

Schultz, Anna. “Uncompromising Mimikry. Heartfield’s Exile in London.” John Heartfield. Photography Plus Dynamite, edited by Angela Lammert et al., exh. cat. Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Hirmer, 2020, pp. 195–202.

Vinzent, Jutta. Identity and Image. Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933–1945) (Schriften der Guernica-Gesellschaft, 16). VDG, 2006.

Word Count: 199

Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Archiv Bildende Kunst (Papers of René Graetz, John Heartfield, Heinz Worner).

Word Count: 16

My thanks go to Sylvia Asmus and Katrin Kokot (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945, Frankfurt am Main) for providing me with the images of Freie Deutsche Kultur.

Word Count: 26

149 Regent Street, Mayfair, London W1.

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Allies inside Germany." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5141-11258777, last modified: 26-04-2021.

-

John HeartfieldArtistGraphic DesignerFotomonteur (mounter of photographs)London

After escaping from his first exile in Prague in December 1938, the political artist John Heartfield lived in London since 1950, working for Picture Post and the publisher Lindsay Drummond.

Word Count: 28

The Warburg InstituteResearch InstituteLondonThe Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in Hamburg achieved a new presence in London after 1933 under the name The Warburg Institute as a research institution with a library and photo archive.

Word Count: 29

Julian HuxleyZoologistPhilosopherWriterLondonJulian Huxley was the director of London Zoo from 1935 to 1942 and worked closely with emigrant photographers, artists and architects, including Berthold Lubetkin, Erna Pinner and Wolf Suschitzky.

Word Count: 27