Archive

Modern Art Gallery

- Modern Art Gallery

- Art Gallery

The Modern Art Gallery, founded by the émigré painter, sculptor and writer Jack Bilbo, was a forum for the presentation of modern art, specialising in the work of emigrant artists.

Word Count: 30

12 Baker Street, Marylebone, London W1 (1941–1943); 24 Charles II Street, St. James’s, London SW1 (1943–1948).

Cover of Jack Bilbo’s The Moderns. Past – Present – Future, published in 1945 under The Modern Art Gallery Ltd imprint (Bilbo 1945).

Jack Bilbo’s Modern Art Gallery was located at 24 Charles II Street, St. James’s, London SW1 from 1943 (Bilbo 1948, 16).

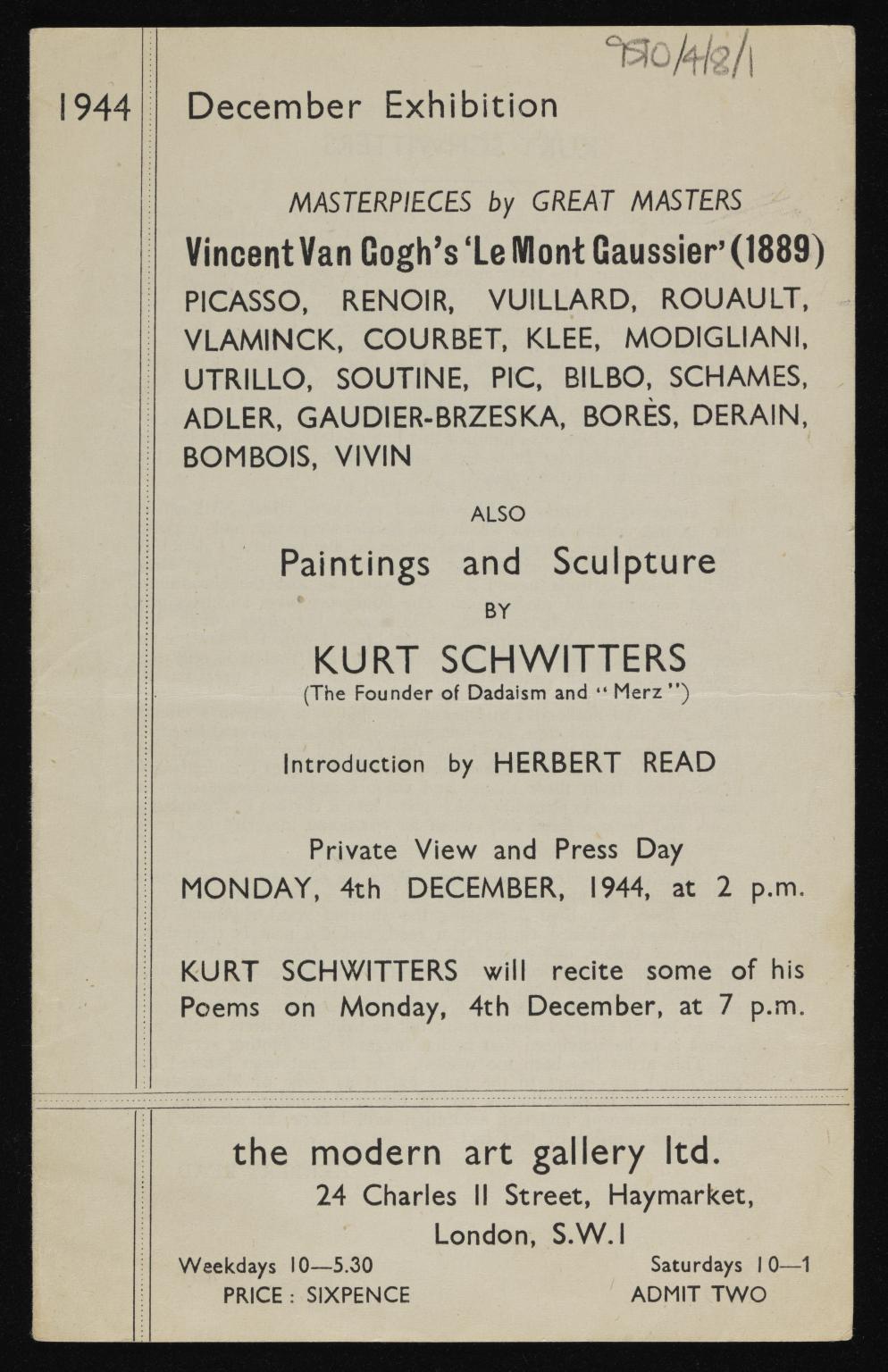

Leaflet advertising the December exhibition held at the Modern Art Gallery on Masterpieces by Great Masters, also featuring Paintings and Sculptures by Kurt Schwitters, Modern Art Gallery Ltd., 1944 (Tate Archive, TGA 9510/4/8/1, Photo © Tate, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)).

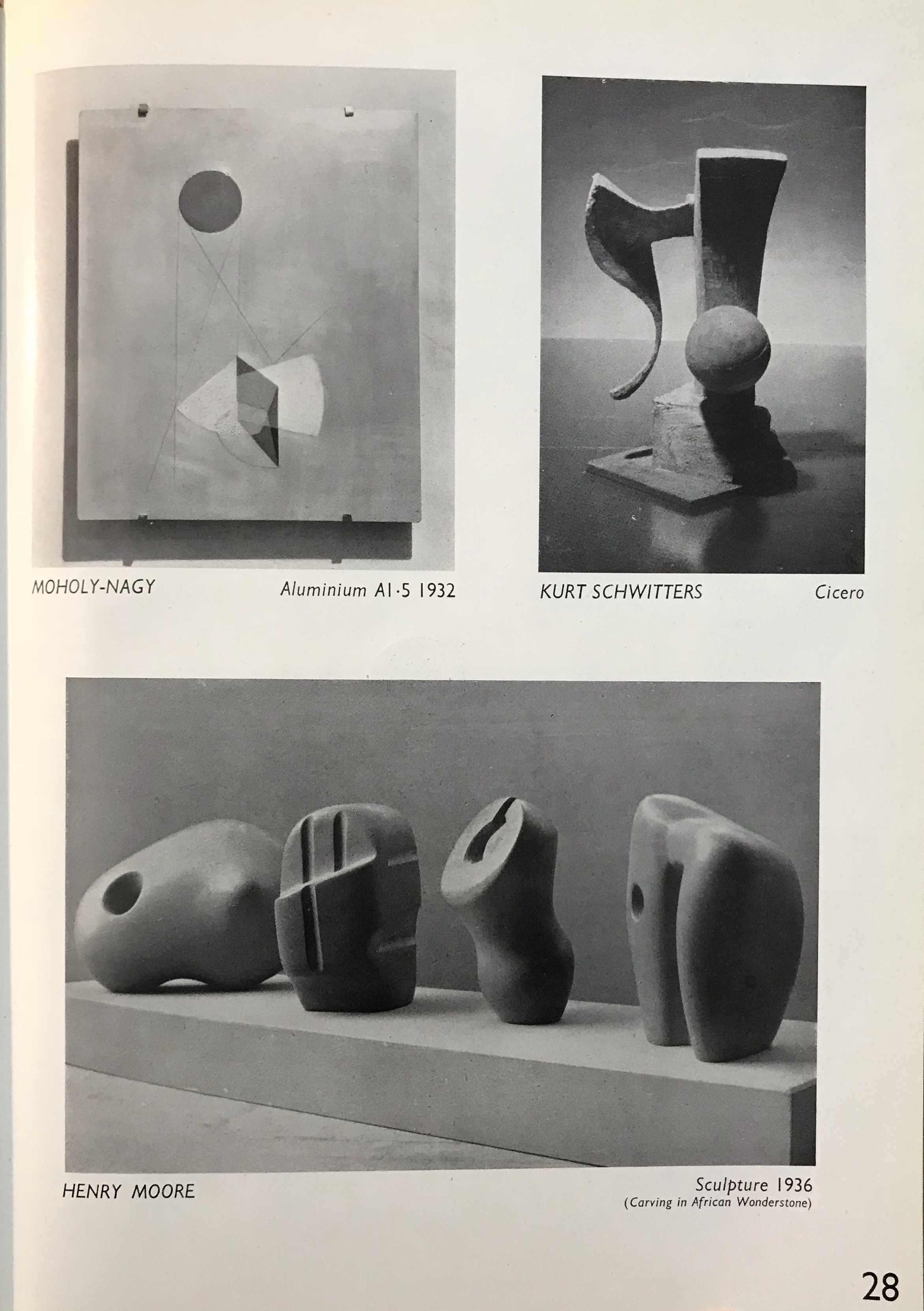

Page with works by László Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters and Henry Moore in Jack Bilbo’s The Moderns. Past – Present – Future, 1945 (Bilbo 1945, 28).

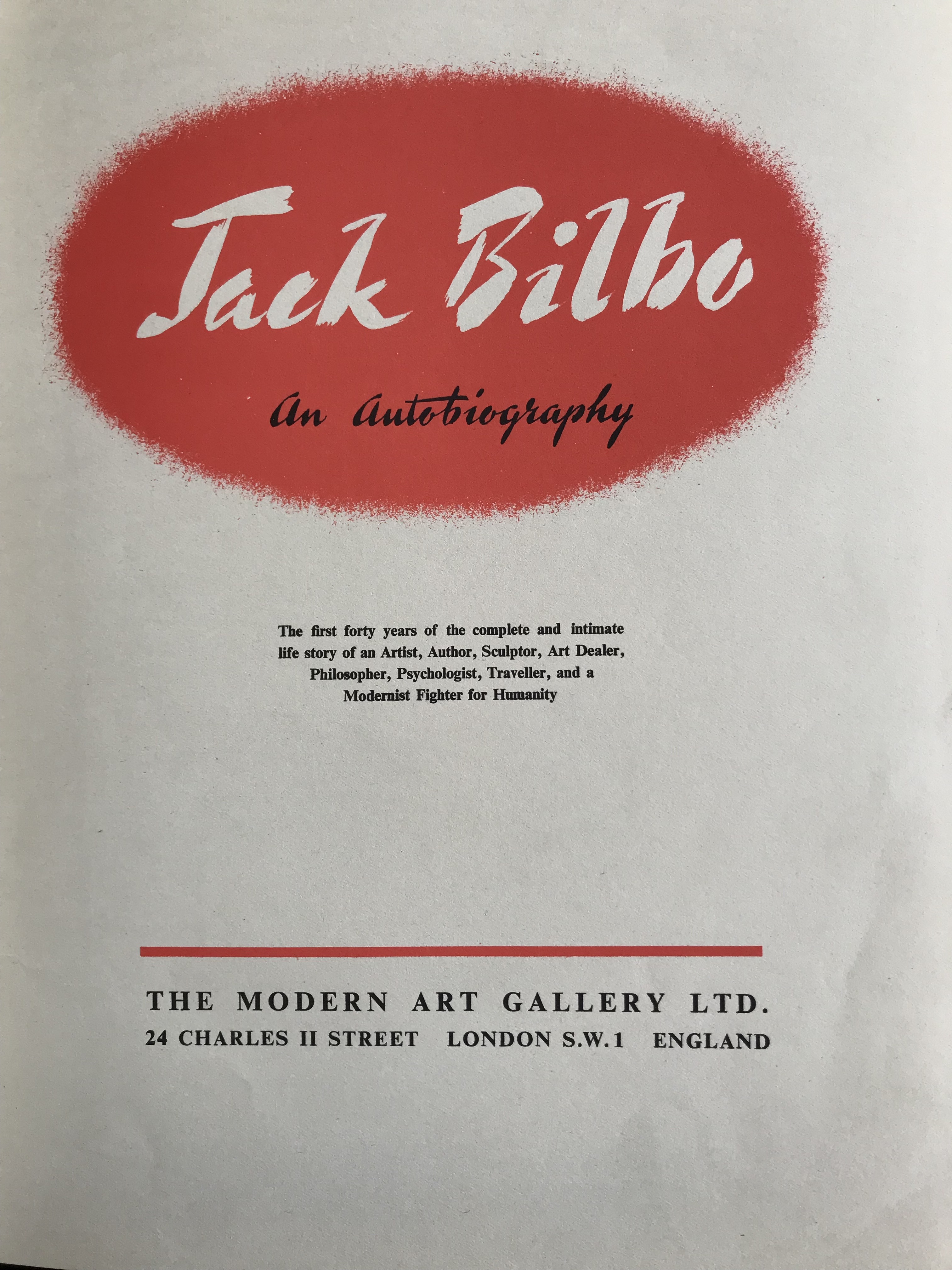

Title page of Jack Bilbo’s book An Autobiography, 1948 (Bilbo 1948).

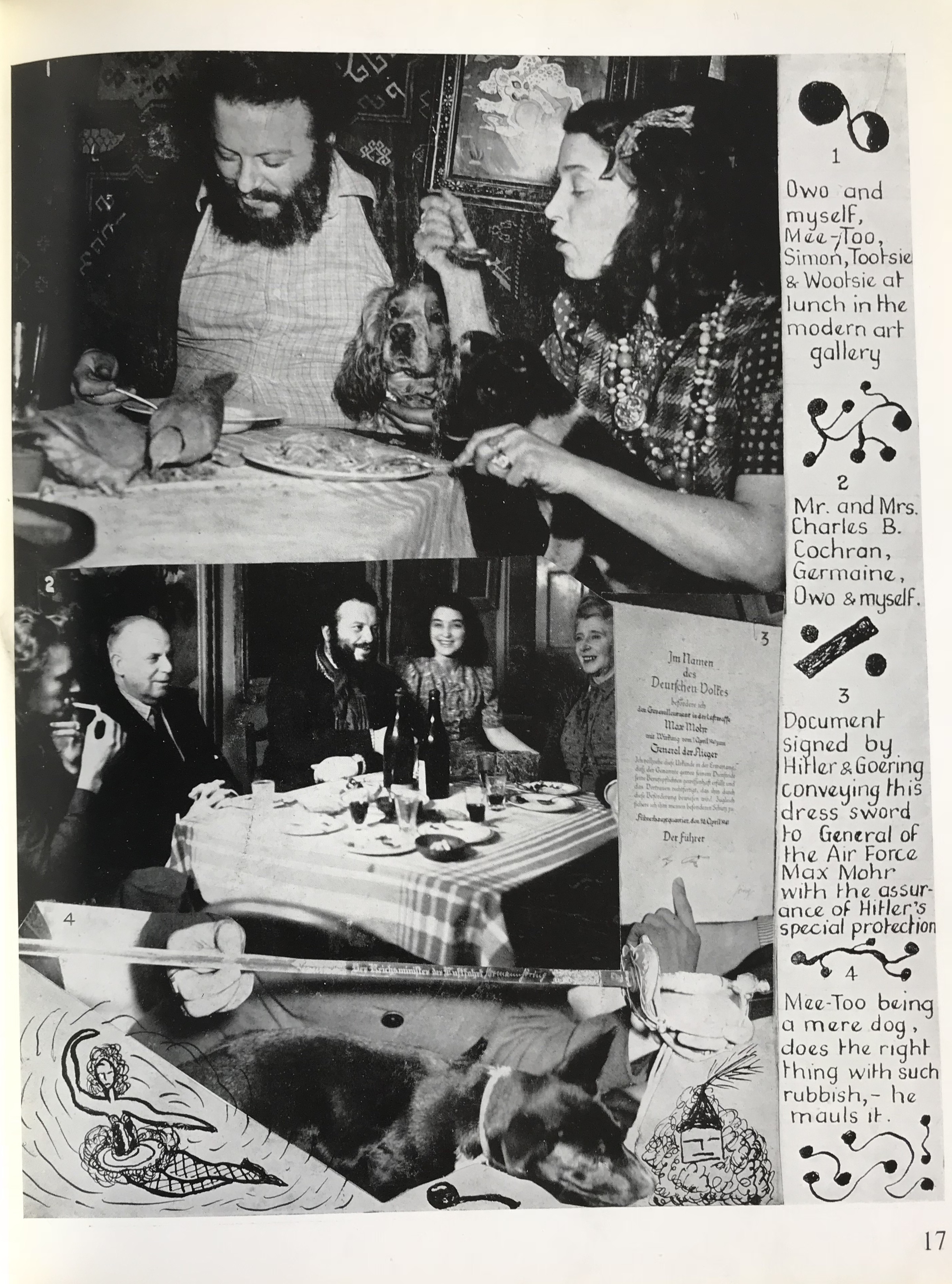

Lunch at Jack Bilbo’s Modern Art Gallery (Bilbo 1948, 17). Bilbo, Jack. Reflections in an Art Gallery. In Celebration of the First Anniversary of the Modern Art Gallery, exh. cat. Modern Art Gallery, London, 1942.

Bilbo, Jack. Pablo Picasso. Thirty important paintings from 1904 to 1943, exh. cat. Modern Art Gallery, London, 1945.

Bilbo, Jack. The Moderns. Past – Present – Future. The Modern Art Gallery Ltd., 1945.

Bilbo, Jack. An Autobiography. The Modern Art Gallery Ltd., 1948.

Bilbo, Jack. Pfui Teufel. Matari Verlag, 1968.

Dickson, Rachel. “‚Our horizon is the barbed wire‘: Artistic Life in the British Internment Camps.” Insiders Outsiders. Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Visual Culture, edited by Monica Bohm-Duchen, Lund Humphries, 2019, pp. 147–156.

Im Atelier Liebermann: Daniel Richter / Jack Bilbo, exh. cat. Stiftung Brandenburger Tor, Max Liebermann Haus, Berlin, 2017.

Käpt’n Bilbo [Jack Bilbo]. Rebell aus Leidenschaft. Abenteurer, Maler, Philosoph. Preface by Henry Miller. Horst Erdmann, 1963.

Kunisch, Hans-Peter. “Jack Bilbo. Unstillbarer Durst nach Freiheit.” Zeit Online, 19 January 2018, www.zeit.de/kultur/literatur/2018-01/jack-bilbo-ludwig-lugmeier-das-leben-des-kaeptn-bilbo-faktenroman. Accessed 16 February 2021.

Lugmeier, Ludwig. Das Leben des Käpt’n Bilbo. Verbrecher Verlag, 2017.

Pross, Steffen. “In London treffen wir uns wieder”. Vier Spaziergänge durch ein vergessenes Kapitel deutscher Kulturgeschichte nach 1933. Eichhorn, 2000.

Vinzent, Jutta. “Muteness as Utterance of a Forced Reality – Jack Bilbo’s Modern Art Gallery (1941–1948).” Arts in Exile in Britain 1933–1945. Politics and Cultural Identity (The Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, 6 (2004)), edited by Shulamith Behr and Marian Malet, Rodopi, 2005, pp. 301–337.

Vinzent, Jutta. Identity and Image. Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933–1945) (Schriften der Guernica-Gesellschaft, 16). VDG, 2006.

Woodeson, Merry Kerr. “Jack Bilbo und seine ‚Modern Art Gallery‘. London 1941–1946.” Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 1986, pp. 49–52.

Word Count: 273

- 1941

- 1948

Jack Bilbo.

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Modern Art Gallery." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5145-11259742, last modified: 19-06-2021.

-

Kurt SchwittersArtistPoetLondon

The artist and poet Kurt Schwitters lived in London between 1941 and 1945, where he stood in contact to émigré and local artists, before moving to the Lake District.

Word Count: 27

Herbert ReadArt HistorianArt CriticPoetLondonThe British art historian Herbert Read established himself as a central figure in the London artistic scene in the 1930s and was one of the outstanding supporters of exiled artists.

Word Count: 30

Ludwig Meidner, Drawings 1920–1922 and 1935–49, Else Meidner, Paintings and Drawings 1935–1949ExhibitionLondonIn 1949, a joint exhibition of works by Ludwig and Else Meidner opened at the Ben Uri Art Gallery. It was the first solo exhibition of the artists in London.

Word Count: 29

László Moholy-NagyPhotographerGraphic DesignerPainterSculptorLondonLászló Moholy-Nagy emigrated to London in 1935, where he worked in close contact with the local avantgarde and was commissioned for window display decoration, photo books, advertising and film work.

Word Count: 30

Marlborough Fine ArtArt GalleryLondonMarlborough Fine Art was founded in 1946 by the Viennese emigrants Harry Fischer and Frank Lloyd in the Mayfair district, focused on Impressionists, Modern and Contemporary Art.

Word Count: 26

Hanover GalleryArt GalleryLondonThe Hanover Gallery was founded by Erica Brausen and dedicated to interwar modernism and contemporary art, supporting the early careers of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Niki de Saint Phalle.

Word Count: 30

St. George’s GalleryArt GalleryLondonIn 1943, the art dealer Lea Bondi Jaray, with support of Otto Brill, also exiled from Vienna, took over St. George’s Gallery in Mayfair, exhibiting contemporary British and continental art.

Word Count: 30