Archive

St. George’s Gallery

- St. George’s Gallery

- Art Gallery

In 1943, the art dealer Lea Bondi Jaray, with support of Otto Brill, also exiled from Vienna, took over St. George’s Gallery in Mayfair, exhibiting contemporary British and continental art.

Word Count: 30

81 Grosvenor Street, Mayfair, London W1.

Honoré Daumier. Lithographs, exh. cat. St. George’s Gallery, London, June 1946, cover (METROMOD Archive).

Honoré Daumier. Lithographs, exh. cat. St. George’s Gallery, London, June 1946, p. 5 with Denys Sutton’s essay “Honoré Daumier” (METROMOD Archive).

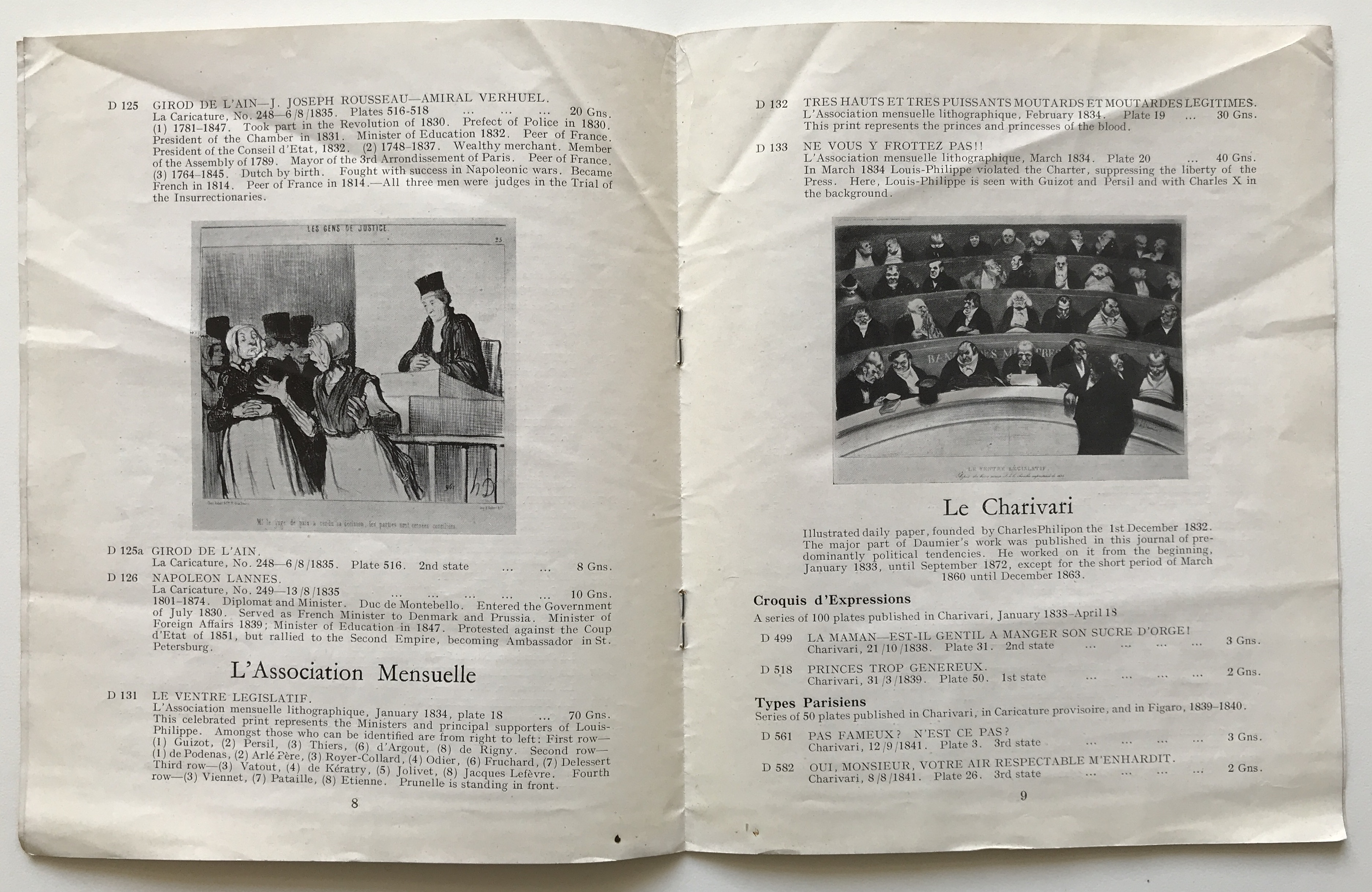

Honoré Daumier. Lithographs, exh. cat. St. George’s Gallery, London, June 1946, p. 8–9 (METROMOD Archive).

Announcement of the Waldemar Stabell exhibition at St. George’s Gallery, London, in The Observer, 19 January 1947, p. 7 (Photo: Private Archive).

Review of the exhibition of Mary Swanzy and Mary Krishna at St. George’s Gallery, London, in The Observer, 30 March 1947, p. 2 (Photo: Private Archive).

Review of The New Generation exhibition with Lucian Freud, John Craxton and William Scott at St. George’s Gallery, London, in The Observer, 11 May 1947, p. 2 (Photo: Private Archive).

Announcement of The Known and Unknown Paintings by British and Continental artists exhibition at St. George’s Gallery, London, in The Observer, 17 August 1947, p. 7 (Photo: Private Archive). Anderl, Gabriele, and Alexandra Caruso, editors. NS-Kunstraub in Österreich und die Folgen. Studien Verlag, 2005.

Anonymous. “Our London Correspondence.” The Manchester Guardian, 12 December 1949, p. 4.

Anonymous. „Jüdische Sammler und Kunsthändler (Opfer nationalsozialistischer Verfolgung und Enteignung).” Lost Art-Datenbank Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste, http://www.lostart.de/Content/051_ProvenienzRaubkunst/DE/Sammler/B/Brill,%20Otto.html. Accessed 5 February 2021.

Aronowitz, Richard, and Shauna Isaac. “Émigré Art Dealers and Collectors.” Insiders Outsiders. Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Visual Culture, edited by Monica Bohm-Duchen, Lund Humphries, 2019, pp. 129–135.

Collis, Maurice. “Art.” The Observer, 1 September 1946a, p. 2.

Collis, Maurice. “Paintings. A Gallery Reopens.” The Observer, 22 December 1946b, p. 2.

Dobrzynski, Judith H. “The Zealous Collector. A Singular Passion For Amassing Art, One Way or Another.” The New York Times, 24 December 1997. Pundicity / Judith H. Dobrzynksi, http://www.judithdobrzynski.com/3016/the-zealous-collector. Accessed 5 February 2021.

Heartfield, John. “Daumier im ‘Reich’.” Freie Deutsche Kultur, no. 2, 1942, pp. 7–8.

Moholy, Lucia. A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939. Penguin Books, 1939.

Rohringer, Susanne. “Recollecting. Raub und Restitution: Entzogenes Leben.” 31 January 2009, artmagazine, https://www.artmagazine.cc/content38095.html. Accessed 5 February 2009.

Scarisbrick, Diana. “Obituary: Agatha Sadler: Refugee from the Nazis who became a much admired bookseller and art collector.” The Independent, 2 February 2016, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/agatha-sadler-refugee-nazis-who-became-much-admired-bookseller-and-art-collector-a6849596.html. Accessed 1 March 2021.

Schnabel, Gunnar, and Monika Tatzkow. Nazi Looted Art. Handbuch Kunstrestitution weltweit. proprietas-verlag, 2007.

Summers, Cherith. “St. George’s Gallery.” Brave New Visions. The Émigrés who transformed the British Art World, exh. cat. Sotheby’s, St. George’s Gallery, London, 2019, p. 28. issuu, https://issuu.com/bravenewvisions/docs/brave_new_visions. Accessed 25 February 2021.

Word Count: 255

- 1943

- 1950

Lea Bondi Jaray, Otto Brill, Agathe Sadler.

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "St. George’s Gallery." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5145-11259763, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939BookLondon

Six years after her arrival in London, the photographer Lucia Moholy published her book A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939, on the occasion of the centenary of photography.

Word Count: 27

Marlborough Fine ArtArt GalleryLondonMarlborough Fine Art was founded in 1946 by the Viennese emigrants Harry Fischer and Frank Lloyd in the Mayfair district, focused on Impressionists, Modern and Contemporary Art.

Word Count: 26

Hanover GalleryArt GalleryLondonThe Hanover Gallery was founded by Erica Brausen and dedicated to interwar modernism and contemporary art, supporting the early careers of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Niki de Saint Phalle.

Word Count: 30

Modern Art GalleryArt GalleryLondonThe Modern Art Gallery, founded by the émigré painter, sculptor and writer Jack Bilbo, was a forum for the presentation of modern art, specialising in the work of emigrant artists.

Word Count: 30

John HeartfieldArtistGraphic DesignerFotomonteur (mounter of photographs)LondonAfter escaping from his first exile in Prague in December 1938, the political artist John Heartfield lived in London since 1950, working for Picture Post and the publisher Lindsay Drummond.

Word Count: 28