Archive

Reimann School, London

- Reimann School, London

- Art School

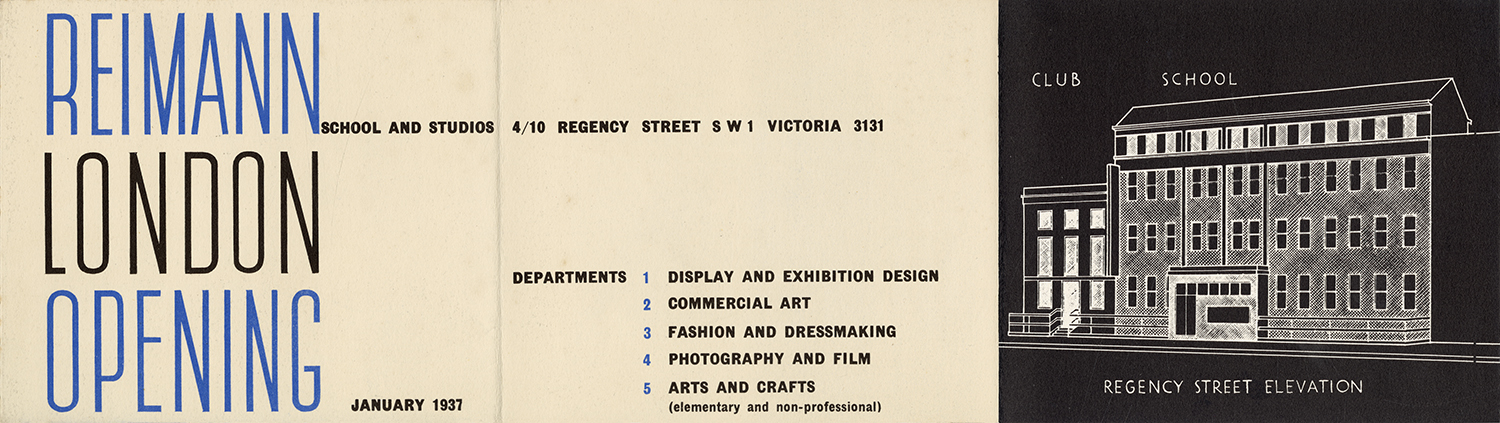

The Reimann School in London opened in 1937 and was a branch of the Berlin Schule Reimann, training students in commercial art and industrial design.

Word Count: 24

4–10 Regency Street, Pimlico, London SW1.

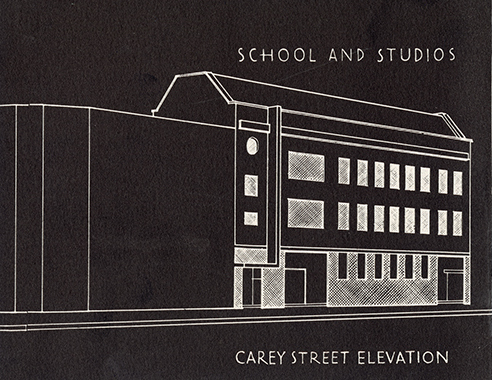

Reimann School, London, leaflet, January 1937, detail (HA Rothholz Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives).

Reimann School, London, leaflet, January 1937, front cover (HA Rothholz Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives).

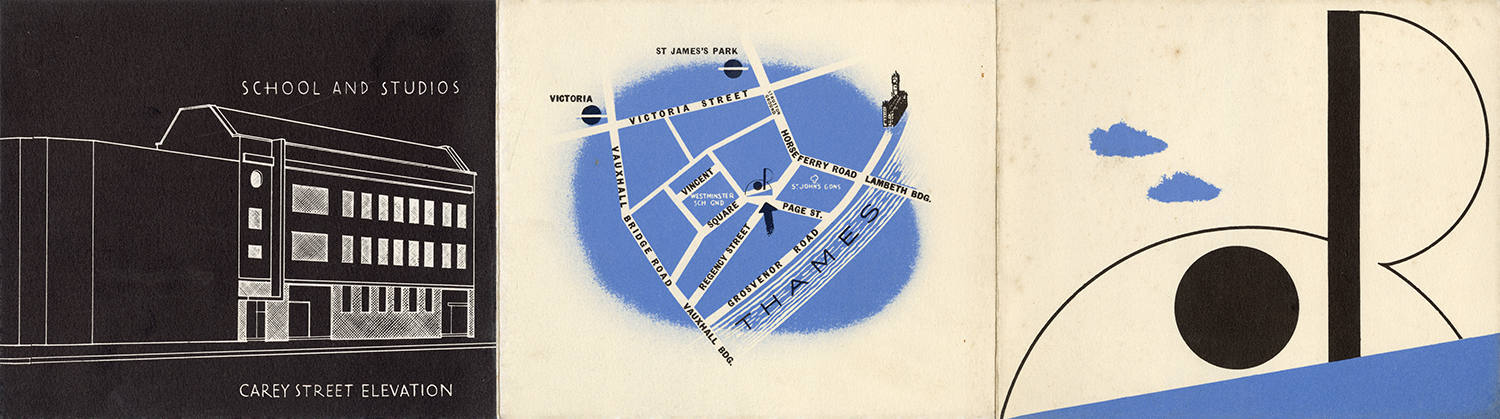

Reimann School, London, leaflet, January 1937, back cover (HA Rothholz Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives).

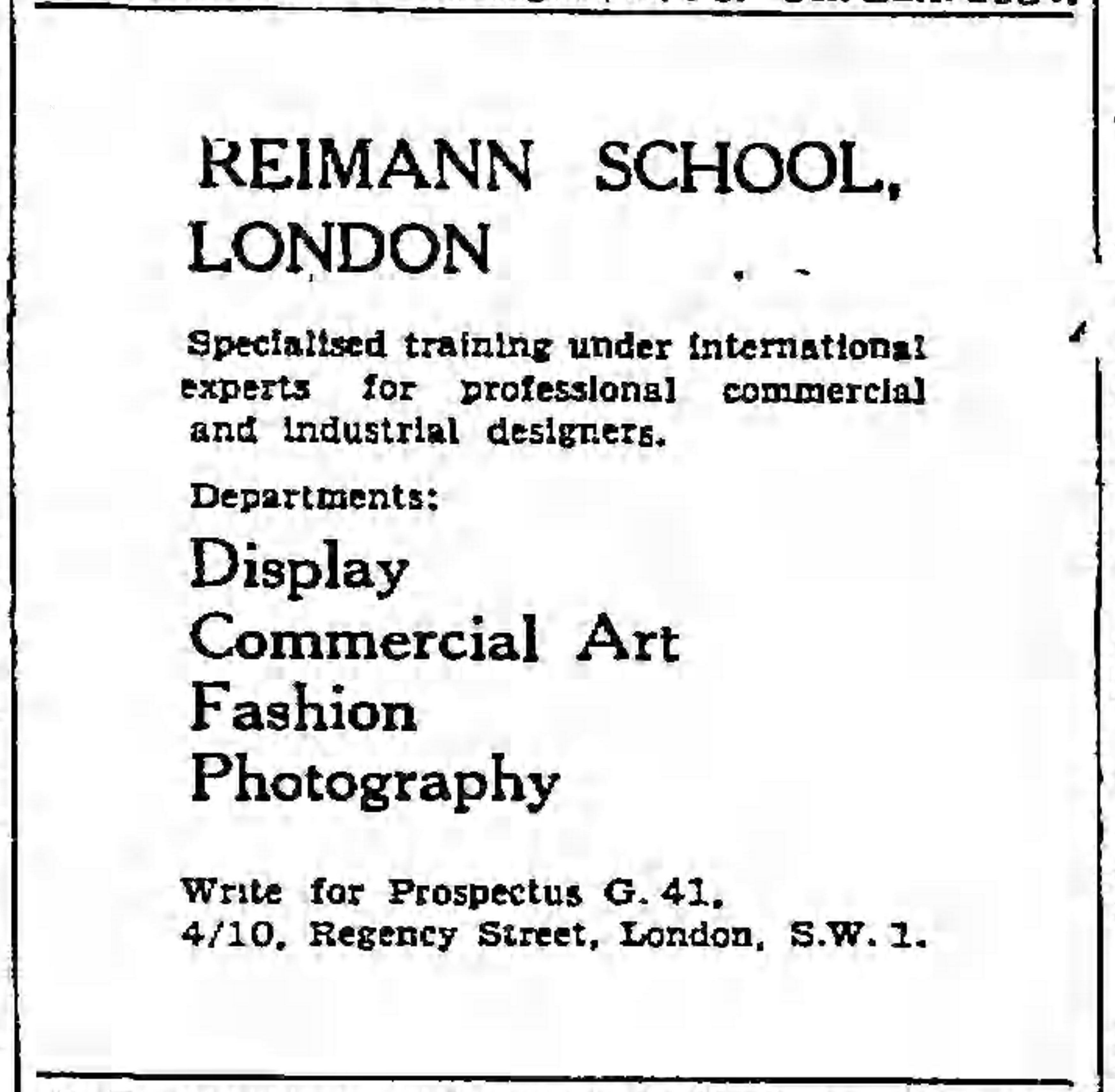

Advertisement for Reimann School, London in The Manchester Guardian, 24 February 1938, p. 1 (Photo: Private Archive).

Private Wire. “New School for Commercial Art.” The Manchester Guardian, 13 January 1937, p. 10 (Photo: Private Archive).

Anonymous. “Canadians in Art World in Britain.” The Province, 28 January 1939, p. 45 (Photo: Private Archive). Article mentioning the diploma of a young Canadian student. Anonymous. “Commercial and Industrial Art: The Reimann School at Work.” The Times, 17 November 1937.

Anonymous. “Canadians in Art World in Britain.” The Province, 28 January 1939, p. 45.

Breakell, Sue, and Lesley Whitworth. “Émigré Designers in the University of Brighton Design Archives.” Journal of Design History, vol. 28, no. 1, 2015, pp. 83–97, doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/ept006.

Games, Naomi. “Dorrit Dekk obituary.” The Guardian, 7 January 2015, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jan/07/dorrit-dekk. Accessed 8 March 2021.

Horwell, Veronica. “Alex Kroll.” The Guardian, 2 July 2008, www.theguardian.com/media/2008/jul/02/pressandpublishing. Accessed 8 March 2021.

Lodge, Bernard. “Natasha Kroll.” The Guardian, 7 April 2004, www.theguardian.com/media/2004/apr/07/broadcasting.guardianobituaries. Accessed 8 March 2021.

Private Wire. “Unexpected Lead from Berlin.” The Manchester Guardian, 20 November 1936, p. 10.

Private Wire. “New School for Commercial Art.” The Manchester Guardian, 13 January 1937, p. 10.

Reimann, Albert. Die Reimann-Schule in Berlin (Schriften zur Berliner Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte, 8). Hessling, 1966.

Shapira, Elana, editor. Designing Transformation. Jews and Cultural Identity in Central European Modernism. Bloomsbury, 2021.

Suga, Yasuko. “Modernism, Commercialism and Display Design in Britain: The Reimann School and Studios of Industrial and Commercial Art.” Journal of Design History, vol. 19, no. 2, 2006, pp. 137–154, doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epl008.

Suga, Yasuko. The Reimann School. A Design Diaspora. Artmonsky Arts, 2013.

Wickenheiser, Swantje. Die Reimann-Schule in Berlin und London (1902–1943). Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Mode- und Textilentwurf (dissertation). Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, 1993.

Wickenheiser, Swantje. Die Reimann-Schule in Berlin und London 1902–1943: Ein jüdisches Unternehmen zur Kunst- und Designausbildung internationaler Prägung bis zur Vernichtung durch das Hitlerregime. Shaker Media, 2009.

Word Count: 238

HA Rothholz Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives.

Word Count: 8

My deepest thanks go to Lesley Whitworth from University of Brighton Design Archives for providing me with images of the Reimann School leaflet.

Word Count: 23

- 1937

- 1941

Austin Cooper, Doritt Dekk, Alex Kroll, Natasha Kroll, Hans Loew, Walter Nurnberg, Hans Reimann, Hildegard Reimann, Manfred Reiss, Hans Arnold Rothholz, Alex Strasser, Else Taterka.

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Reimann School, London." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5145-11260553, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

László Moholy-NagyPhotographerGraphic DesignerPainterSculptorLondon

László Moholy-Nagy emigrated to London in 1935, where he worked in close contact with the local avantgarde and was commissioned for window display decoration, photo books, advertising and film work.

Word Count: 30

Lighting for Photography. Means and MethodsPhoto guideBookLondonLighting for Photography from 1940 by the émigré photographer Walter Nurnberg was one of a number of successful photo guides produced by Andor Kraszna-Krausz’s Focal Press publishing house.

Word Count: 28

Rolf TietgensPhotographerEditorWriterNew YorkRolf Tietgens was a German émigré photographer who arrived in New York in 1938. Although, in the course of his photographic career, his artistic and surrealist images were published and shown at exhibitions, his work, today, is very little known.

Word Count: 39