Archive

The Warburg Institute

- The Warburg Institute

- Research Institute

The Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in Hamburg achieved a new presence in London after 1933 under the name The Warburg Institute as a research institution with a library and photo archive.

Word Count: 29

3 Thames House, Millbank, London SW1 (since 1934); Imperial Institute Buildings, South Kensington, London SW7 (since 1937); Woburn Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1 (since 1958).

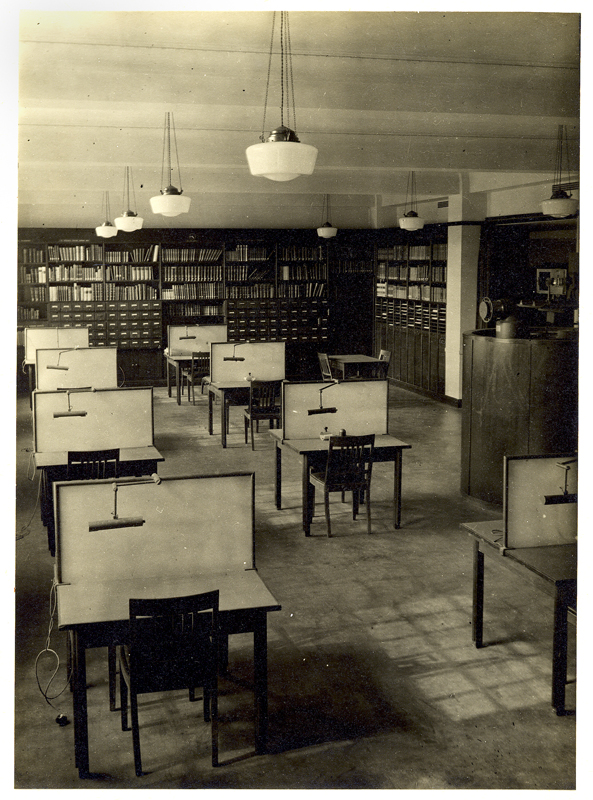

The Warburg Institute, Reading Room, Imperial Institute Building, London, c. 1952 (© The Warburg Institute).

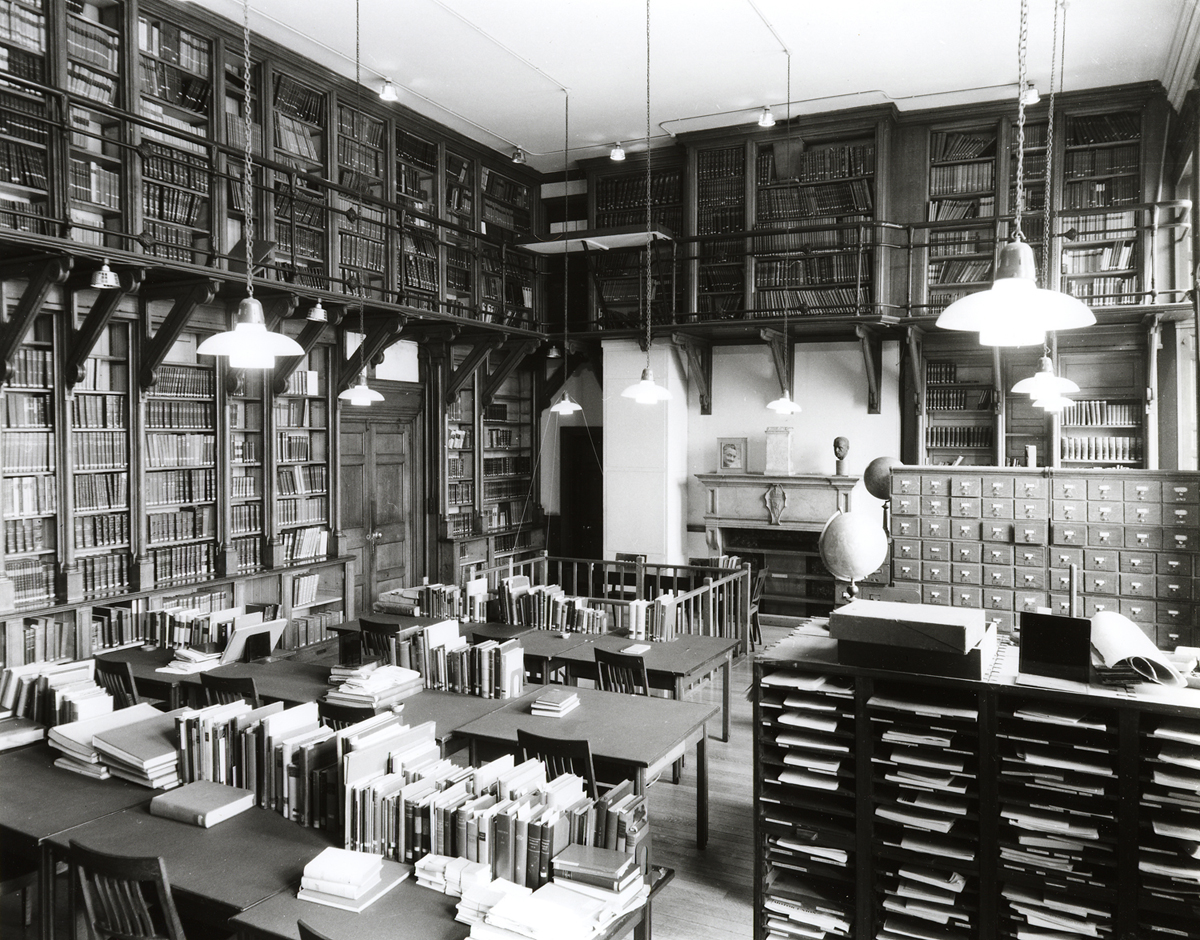

The Warburg Institute, Reading Room, Thames House, London, c. 1934/36 (© The Warburg Institute).

The Warburg Institute, Reading Room, Woburn Square, London, c. 1958 (© The Warburg Institute). Anderson, Joanne W. “Cultural Life and Politics in Wartime London.” Image Journeys. The Warburg Institute and a British Art History (Veröffentlichungen des Zentralinstituts für Kunstgeschichte in München, 49), edited by Joanne Anderson et al., Dietmar Klinger Verlag, 2019, pp. 43–52.

Anderson, Joanne, et al., editors. Image Journeys. The Warburg Institute and a British Art History (Veröffentlichungen des Zentralinstituts für Kunstgeschichte in München, 49). Dietmar Klinger Verlag, 2019.

Anglo, Sydney. “From South Kensington to Bloomsbury and Beyond. The Intellectual Life of the Early Warburg Institute.” The Afterlife of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg. The Emigration and the Early Years of the Warburg Institute in London (Vorträge aus dem Warburg-Haus, 12), edited by Uwe Fleckner and Peter Mack, De Gruyter, 2015, pp. 65–70.

Beiersdorf, Leonie. “‘Wieder Boden unter den Füssen’ – Rosa Schapire in England (1939–1954).” Rosa. Eigenartig grün. Rosa Schapire und die Expressionisten, edited by Sabine Schulze, exh. cat. Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Hamburg, 2009, pp. 250–281.

Fleckner, Uwe, and Peter Mack, editors. The Afterlife of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg. The Emigration and the Early Years of the Warburg Institute in London (Vorträge aus dem Warburg-Haus, 12). De Gruyter, 2015.

Gombrich, Ernst H. Aby Warburg. An Intellectual Biography. Warburg Institute, 1970.

Gramberg, Werner. “In Memoriam Gertrud Bing.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, vol. 11, no. 4, September 1965, pp. 293–295. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27652159. Accessed 11 April 2021.

Hönes, Hans Christian. “‘A very specialized subject’: Art History in Britain.” Insiders Outsiders. Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Visual Culture, edited by Monica Bohm-Duchen, Lund Humphries, 2019, pp. 97–103.

Mann, Nicholas. “Past, present and future.” Porträt aus Büchern. Bibliothek Warburg und Warburg Institute. Hamburg – 1933 – London, edited by Michael Diers, exh. cat. Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky, Hamburg, 1993, pp. 133–143.

Mazzucco, Katia. “1941 English Art and the Mediterranean. A photographic exhibition by the Warburg Institute in London.” Journal of Art Historiography, no. 5, December 2011, https://arthistoriography.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/mazzuccowi-k.pdf. Accessed 22 March 2021.

McEwan, Dorothea. “Exhibitions as Morale Boosters. The Exhibition Programme of the Warburg Institute 1938–1945.” Arts in Exile in Britain 1933–1945. Politics and Cultural Identity (The Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, 6 (2004)), edited by Shulamith Behr and Marian Malet, Rodopi, 2005, pp. 267–300.

McEwan, Dorothea. “Why Historiography? Fritz Saxl’s Thoughts on History and Writing History.” The Afterlife of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg. The Emigration and the Early Years of the Warburg Institute in London (Vorträge aus dem Warburg-Haus, 12), edited by Uwe Fleckner and Peter Mack, De Gruyter, 2015, pp. 97–115.

Müller, Johannes von. “‘under the most difficult circumstances’. Exhibitions at the Warburg Institute, 1933–45.” Image Journeys. The Warburg Institute and a British Art History (Veröffentlichungen des Zentralinstituts für Kunstgeschichte in München, 49), edited by Joanne Anderson et al., Dietmar Klinger Verlag, 2019, pp. 29–42.

Schapire, Rosa. Letter to Fritz Saxl (Archive of The Warburg Institute, London, 22 January 1939).

Treml, Martin, and Sigrid Weigel. “Einleitung.” Aby Warburg. Werke in einem Band. Auf der Grundlage der Manuskripte und Handexemplare, edited by Martin Treml et al., Suhrkamp, 2010, pp. 9–27.

Warburg, Eric M. “The Transfer of the Warburg Institute to England.” The Warburg Institute Annual Report 1952–1953, n.d. [1953], pp. 13–16.

Wuttke, Dieter. “Die Emigration der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Bibliothek Warburg und die Anfänge des Universitätsfaches Kunstgeschichte in Großbritannien.” Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien 1933–1945, exh. cat. Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 1986, pp. 209–215.

Word Count: 545

The Warburg Institute, London.

Word Count: 4

My deepest thanks go to Claudia Wedepohl (Warburg Institute) for giving me permission to reproduce the images of the Warburg Institute, London.

Word Count: 22

- 1934

Gertrud Bing, Ernst H. Gombrich, Fritz Saxl, Rudolf Wittkower.

- London

- Burcu Dogramaci. "The Warburg Institute." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5145-11267218, last modified: 12-05-2021.

-

Rosa SchapireArt HistorianLondon

The art historian Rosa Schapire, a supporter of Expressionist art, contributed to the presence of Expressionist art in England with loans and donations from her art collections rescued to London.

Word Count: 30

Herbert ReadArt HistorianArt CriticPoetLondonThe British art historian Herbert Read established himself as a central figure in the London artistic scene in the 1930s and was one of the outstanding supporters of exiled artists.

Word Count: 30

Focus on Architecture and SculptureBookLondonFocus on Architecture and Sculpture by émigré photographer Helmut Gernsheim brought together his work and experience as a photographer for the National Buildings Record (NBR).

Word Count: 25

The Story of ArtBookLondonThe Story of Art by the émigré art historian Ernst H. Gombrich was published in 1950 with Phaidon Press. The book is a comprehensive and accessible introduction to visual culture.

Word Count: 29

Die ZeitungNewspaperLondonFrom 1941 to 1945, the émigré German-language newspaper Die Zeitung was published in London, reporting on the war on the continent and on the situation in Germany.

Word Count: 25

My Life, My StageBookLondonMy Life, My Stage is the autobiography of costume and set designer Ernest Stern, looking back on his career with director Max Reinhardt, his escape to London and his internment.

Word Count: 30

Visual Pleasures from Everyday ThingsBookletLondonVisual Pleasures from Everyday Things is a booklet written in 1946 by the emigrated architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner with the aim of aesthetic education and teacher training.

Word Count: 26

Allies inside GermanyExhibitionLondonOn 3 July 1942, the Allies inside Germany exhibition, organised by the Free German League of Culture, opened in London in an empty shop at 149 Regent Street.

Word Count: 25

Roland, Browse & DelbancoGalleryArt DealerLondonÉmigré art historians and art dealers, Henry Roland and Gustav Delbanco, along with Lillian Browse, opened their Mayfair gallery, Roland, Browse & Delbanco, in 1945.

Word Count: 24