Archive

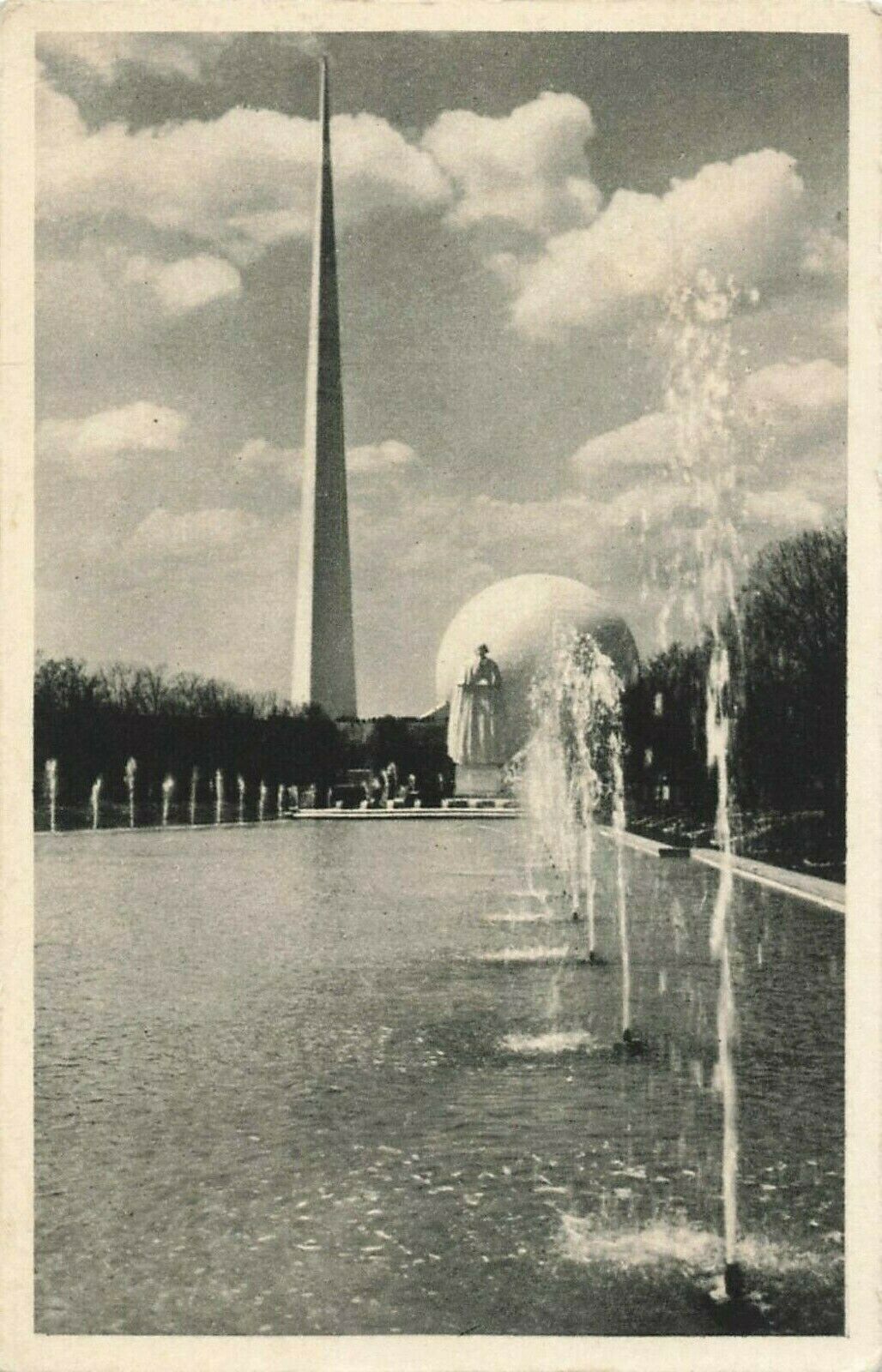

New York World's Fair postcard View of the Constitution Mall looking toward statue of George Washington and Trylon and Perisphere

- Postcard

New York World's Fair postcard View of the Constitution Mall looking toward statue of George Washington and Trylon and Perisphere

Word Count: 20

- Ernest Nash

- 1939

- 1939

paper

World's Fair areal, Flushing Meadows Park, Queens, New York City.

- English

- New York City (US)

Shortly after the arrival in New York in 1939, photographs by the German émigré Ernest Nash were used and reproduced for postcards of the New York’s World’s Fair.

Word Count: 29

New York World's Fair postcard View of the Constitution Mall looking toward statue of George Washington and Trylon and Perisphere, photograph by Ernest Nash, East and West Publishing Company, 1939 (Private Archive Helene Roth).

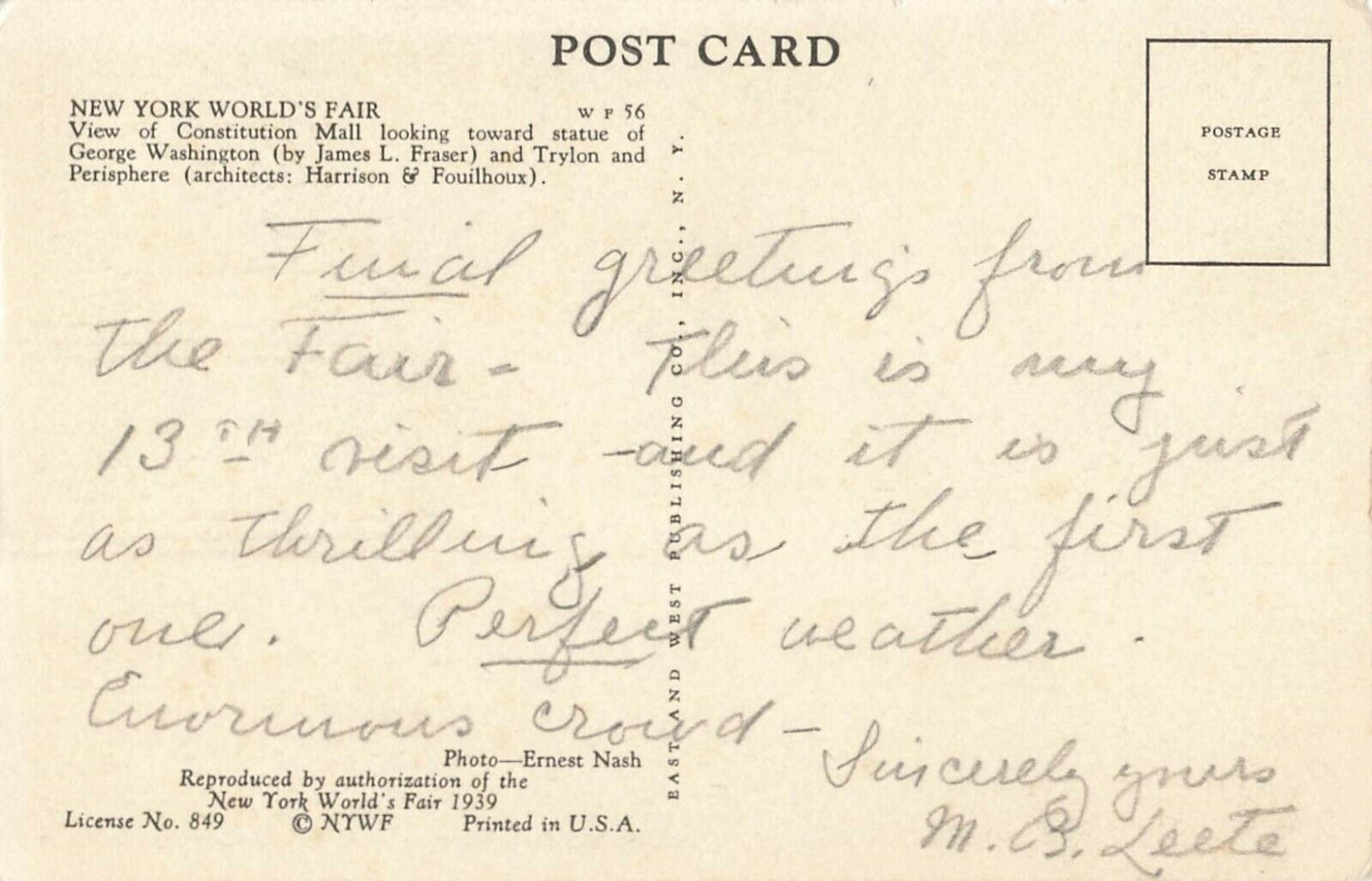

Backside of New York World's Fair postcard View of the Constitution Mall looking toward statue of George Washington and Trylon and Perisphere, photograph by Ernest Nash, East and West Publishing Company, 1939 (Private Archive Helene Roth).

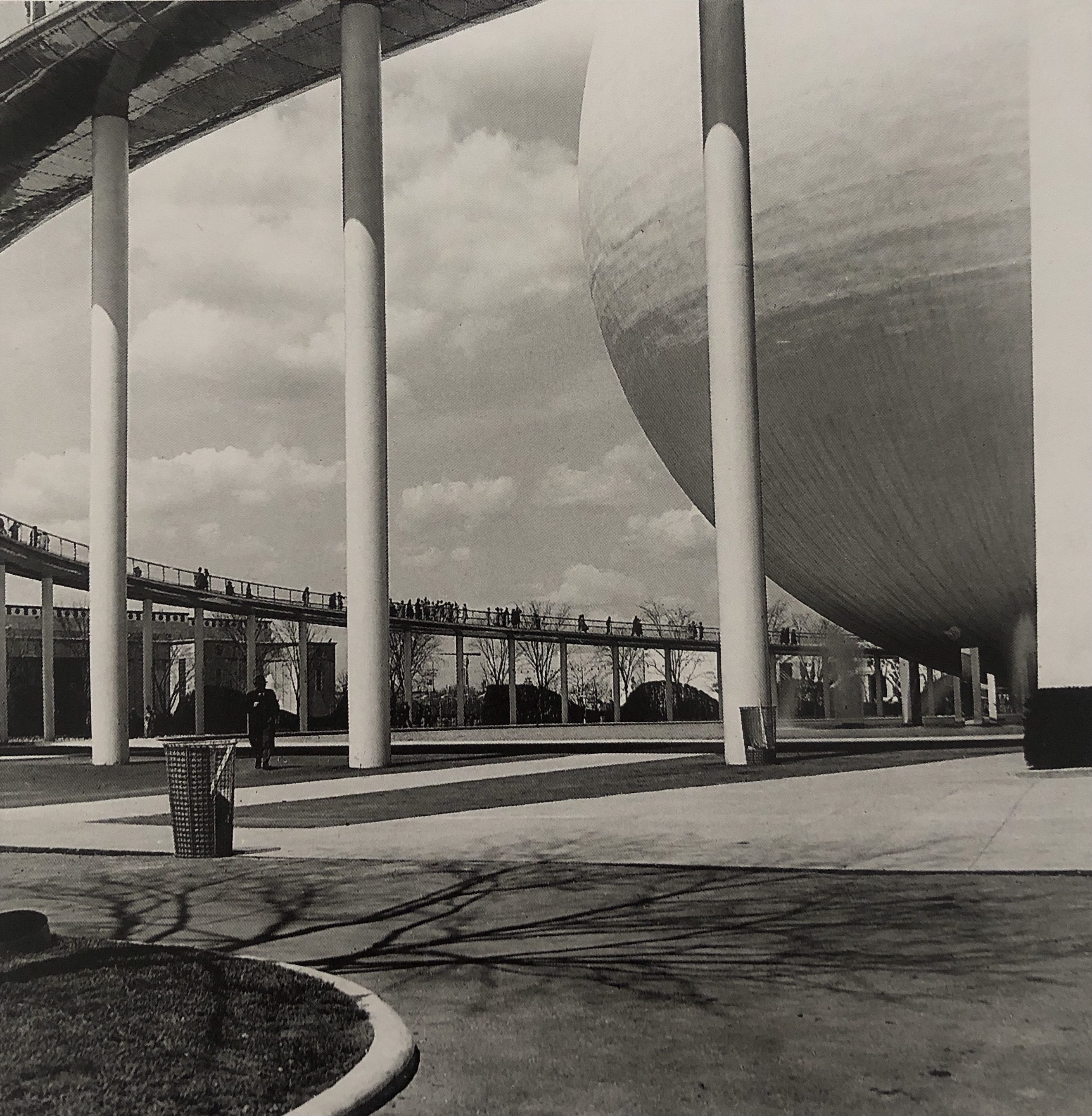

Ernest Nash, New York World’s Fair 1939, Perisphere (© Bildarchiv Ernest Nash, Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main).

Ernest Nash, New York, World’s Fair 1939, Constitution Mall, Trylon and Perisphere (© Bildarchiv Ernest Nash, Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main).

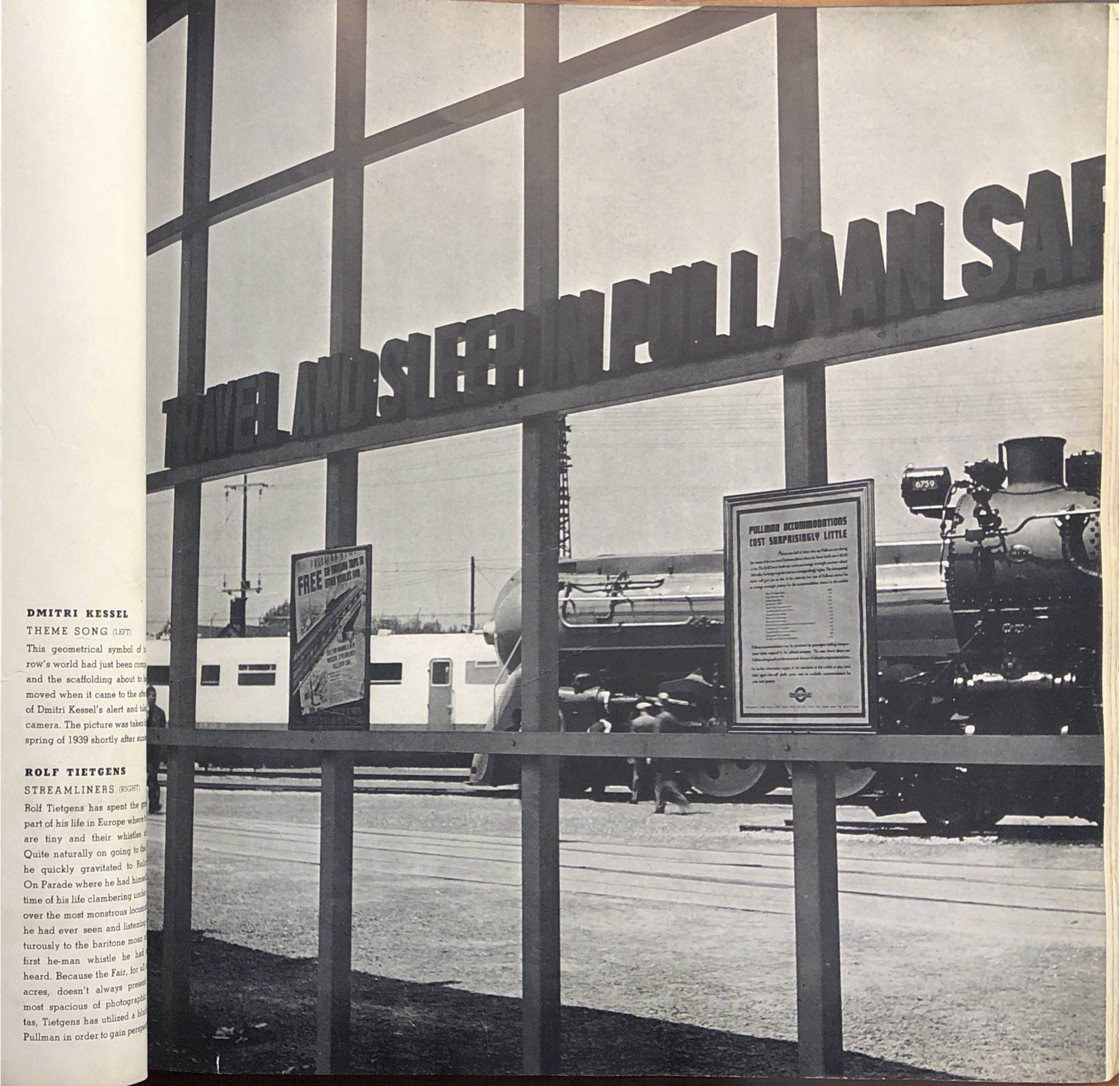

Photo by Rolf Tietgens of Streamliners at the World’s Fair published in the World's Fair special issue of U.S. Camera, August 1939, p. 45 (Photo: Helene Roth).

Photo by Rolf Tietgens of the Communication Mall at the World’s Fair 1939 published in the World's Fair special issue of U.S. Camera, August 1939, p. 38 (Photo: Helene Roth).

Photo of the Aquacade swim show by Walter Sanders for Black Star, reproduced in Life, 3 July 1939, p. 60 (Estate Walter Sanders, Photo: Helene Roth).

“Life goes to The Futurama.” Image of the General Motors Show by Walter Sanders in Life, 5 June 1939, p. 79 (Estate Walter Sanders, Photo: Helene Roth).

Photograph of Amazonian birds by Carola Gregor for the brochure Pavilhão do Brasil. Feira Mundial de Nova York de 1939, p. 13 (Photo: Helene Roth).

Photograph of Amazonian birds by Carola Gregor for the brochure Pavilhão do Brasil. Feira Mundial de Nova York de 1939, pp. 11–12 (Photo: Helene Roth).

Demolition of the World’s Fair by Ruth Bernhard. Reprint of the reportage “Where the World of Tomorrow Is But the Ghost of Yesterday.” The Highway Traveler, vol. 13, no. 2, April-May 1941, pp. 14–15 (© Ruth Bernhard Archive, Special Collection Princeton University © Trustees of Princeton University).

Today’s area of the World’s Fair, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park with the Unisphere (where the Trylon and Perisphere stood) (Photo: Helene Roth, 2019). Alföldi, Maria R., and Margarita C. Lahusen, editors. Ernest Nash – Ernst Nathan: 1898–1974. Photographie Potsdam, Rom, New York, Rom. Nicolai, 2000.

Appelbaum, Stanley. The New York World's Fair 1939/40 in 155 photographs by Richard Wurts and others. Dover Publications, 1977.

Commire, Anne, editor. Something about the Author, vol. 4. Gale Research, 1973.

Corley, Pauline. “Heralding New Books.” The Miami Herald, 12 March 1939, p. 62.

Cotter, Bill. The 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair. Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Federal Writers Project. New York Panorama. A Companion to the WPA Guide to New York City. Pantheon Books, 1938.

Official Guide Book of the New York World's Fair. Expositions Publications, Inc., 1939.

Pavilhão do Brasil. Feira Mundial de Nova York de 1939, edited by Brazil’s Representation to the New York World’s Fair 1939, exh. cat. New York World’s Fair, New York, 1939.

Works Progress Administration. The WPA guide to New York City: The Federal Writers' Project guide to 1930s New York. A comprehensive guide to the five boroughs of the Metropolis - Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, and Richmond. Random House, 1939.

Word Count: 166

New York World's Fair 1939–1940 records, New York Public Library, New York.

Postcard Collection, New Historical Society, New York.

Word Count: 18

World's Fair areal, Flushing Meadows, Queens, New York.

- New York

- Helene Roth. "New York World's Fair postcard View of the Constitution Mall looking toward statue of George Washington and Trylon and Perisphere." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2948/object/5140-11798374, last modified: 23-08-2021.

-

Ernest NashPhotographerArchaeologistLawyerNew York

Ernest Nash was a German born photographer, who pursued his photographic as well as an archeologic interest in Roman architecture after his emigration to New York in 1939. Besides this research interest, he also worked as a portrait photographer and publisher.

Word Count: 40

Ruth StaudingerPhotographerCinematographerArt dealerNew YorkVery few and only fragmentary details can be found on the German émigré photographer Ruth Staudinger, who emigrated in the mid-1930s to New York City. Her nomadic life was also characterisedd by several changes of name along the way.

Word Count: 40

Walter SandersPhotographerNew YorkWalter Sanders was a German émigré photographer. In 1938 he arrived in New York, where he worked from 1939 until the end of his life for the Black Star agency and, from 1944, for Life magazine.

Word Count: 33

Andreas FeiningerPhotographerWriterEditorNew YorkAndreas Feininger, was a German émigré photographer who arrived in New York with his wife Wysse Feininger in 1939. He started a lifelong career exploring the city's streets, working as a photojournalist and writing a large number of photography manuals.

Word Count: 39

Ruth BernhardPhotographerNew YorkRuth Bernhard was a German émigré photographer who lived in New York from the 1920s to the 1940s. Beside her series on female nudes, her place in the photography network, as well as in the New York queer scene, is unknown and understudied.

Word Count: 43

Rolf TietgensPhotographerEditorWriterNew YorkRolf Tietgens was a German émigré photographer who arrived in New York in 1938. Although, in the course of his photographic career, his artistic and surrealist images were published and shown at exhibitions, his work, today, is very little known.

Word Count: 39

Lilo HessPhotographerNew YorkThe German émigré Lilo Hess was an animal photographer working for the Museum for Natural History and the Bronx Zoo, as well being a freelance photographer and publisher of children's books.

Word Count: 31

Carola GregorPhotographerSculptorNew YorkThe German émigré photographer Carola Gregor was an animal and child photographer and published some of her work in magazines and books. Today her work and life are almost forgotten.

Word Count: 30

Black Star AgencyPhoto AgencyNew YorkThe German émigrés Kurt S(z)afranski, Ern(e)st Mayer and Kurt Kornfeld founded Black Star in 1936. The photo agency established was a well-run networking institution in New York.

Word Count: 31