Archive

Dimitri Ismailovitch

- Dimitri

- Ismailovitch

Дмитрий Васильевич Измайлович, Дмитро Васильович Ізмайлович, Dmitriy Ismailovitch, Dimitri Ismaelovitch, Dimitri İzmailovitsch, Dimitri Izmaïlowitch, Dimitri İsmailoviç

- 11-04-1890

- Sataniv (UA)

- 15-10-1976

- Rio de Janeiro (BR)

- PainterArt Historian

In Istanbul, Ismailovitch became one of the leaders of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, organised three solo exhibitions, and made contribution to the study of Byzantine art.

Word Count: 29

Dimitri Ismailovitch with his bust created by Polish sculptor Roman Bilinski, Istanbul, Summer 1922. Source: Scrapbook “To Mr. and Mrs. Stearns from Russian Painters”, p. 8 (Stearns Family Papers. Archives & Special Collections. The College of the Holy Cross).

Dimitri Ismailovitch, 1907, Sumy Cadet Corps (with permission from https://www.ria1914.info/).

Dimitri Ismailovitch with his bust created by Polish sculptor Roman Bilinski, Istanbul, Summer 1922. Source: Scrapbook “To Mr. and Mrs. Stearns from Russian Painters”, p. 8 (Stearns Family Papers. Archives & Special Collections. The College of the Holy Cross).

Reproduction of the Kariye Mosque’s mosaic. In the foreground is its author, Dimitri Ismailovitch (Russkiye na Bosfore. Les Russes sur le Bosphore Almanac, 1928, n.p.).

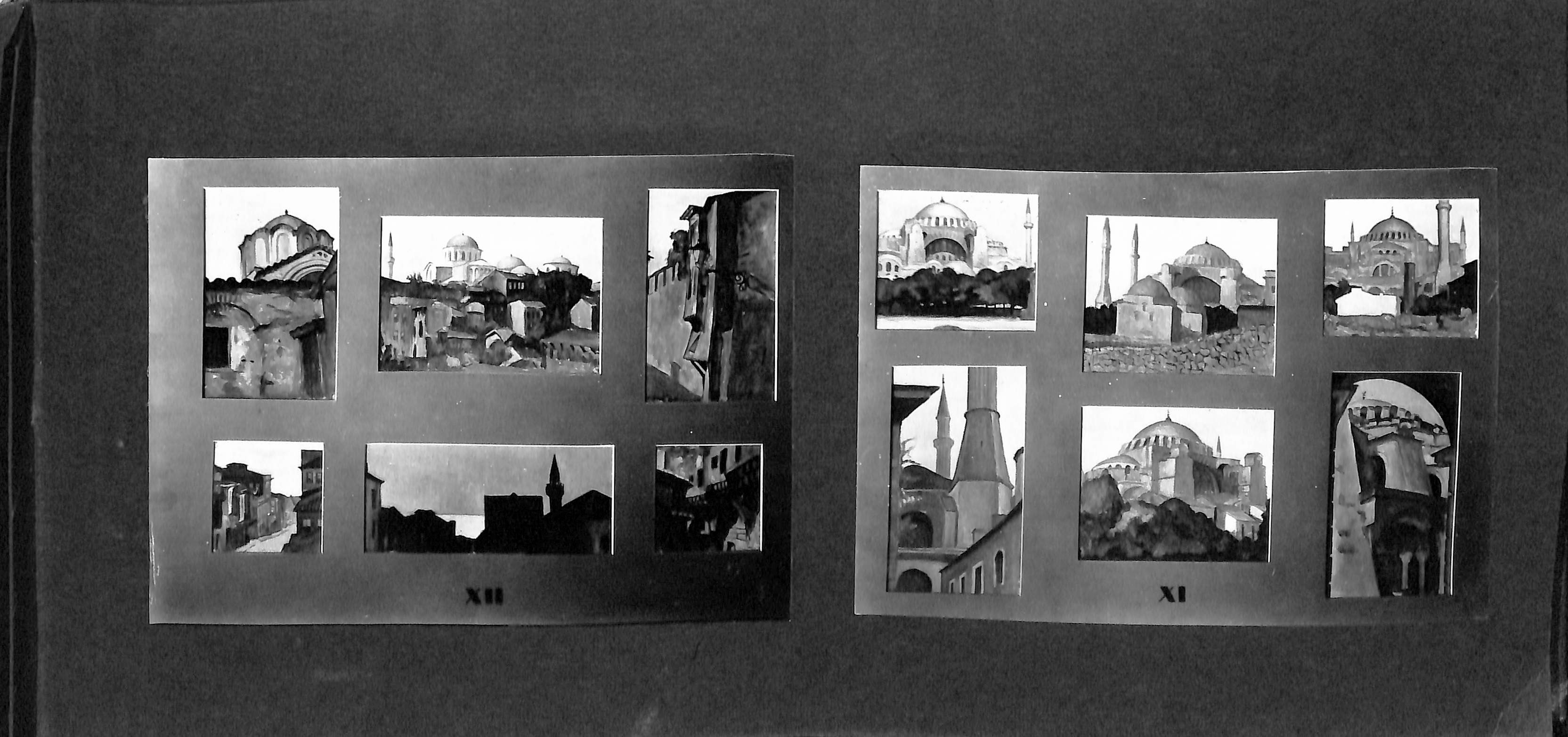

Photographs of the artworks by Dimitri Ismailovitch, 1923. Source: Album “To Mr. and Mrs. Stearns from D. Ismailovitch”, XII–XI, p. 11 (Stearns Family Papers. Archives & Special Collections. The College of the Holy Cross).

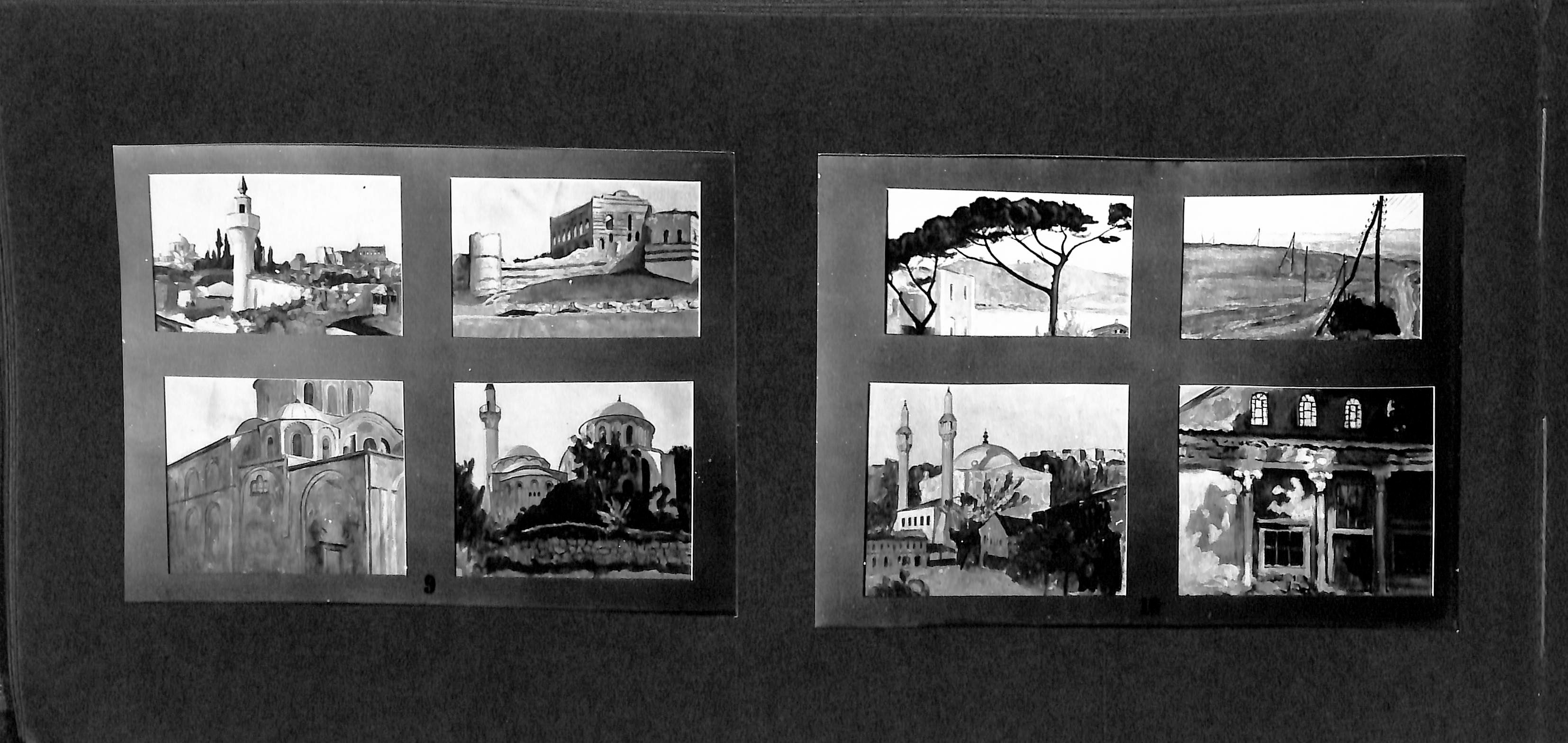

Photographs of the artworks by Dimitri Ismailovitch, 1924. Source: Album “To Mr. and Mrs. Stearns from D. Ismailovitch”, 9–10, p. 24 (Stearns Family Papers. Archives & Special Collections. The College of the Holy Cross).

Photographs of the artworks by Dimitri Ismailovitch. Source: Album “To Mr. and Mrs. Stearns from D. Ismailovitch”, p. 36 (Stearns Family Papers. Archives & Special Collections. The College of the Holy Cross).

Front cover of the 1948 Dimitri İsmailovitch exhibition catalogue (© Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux).

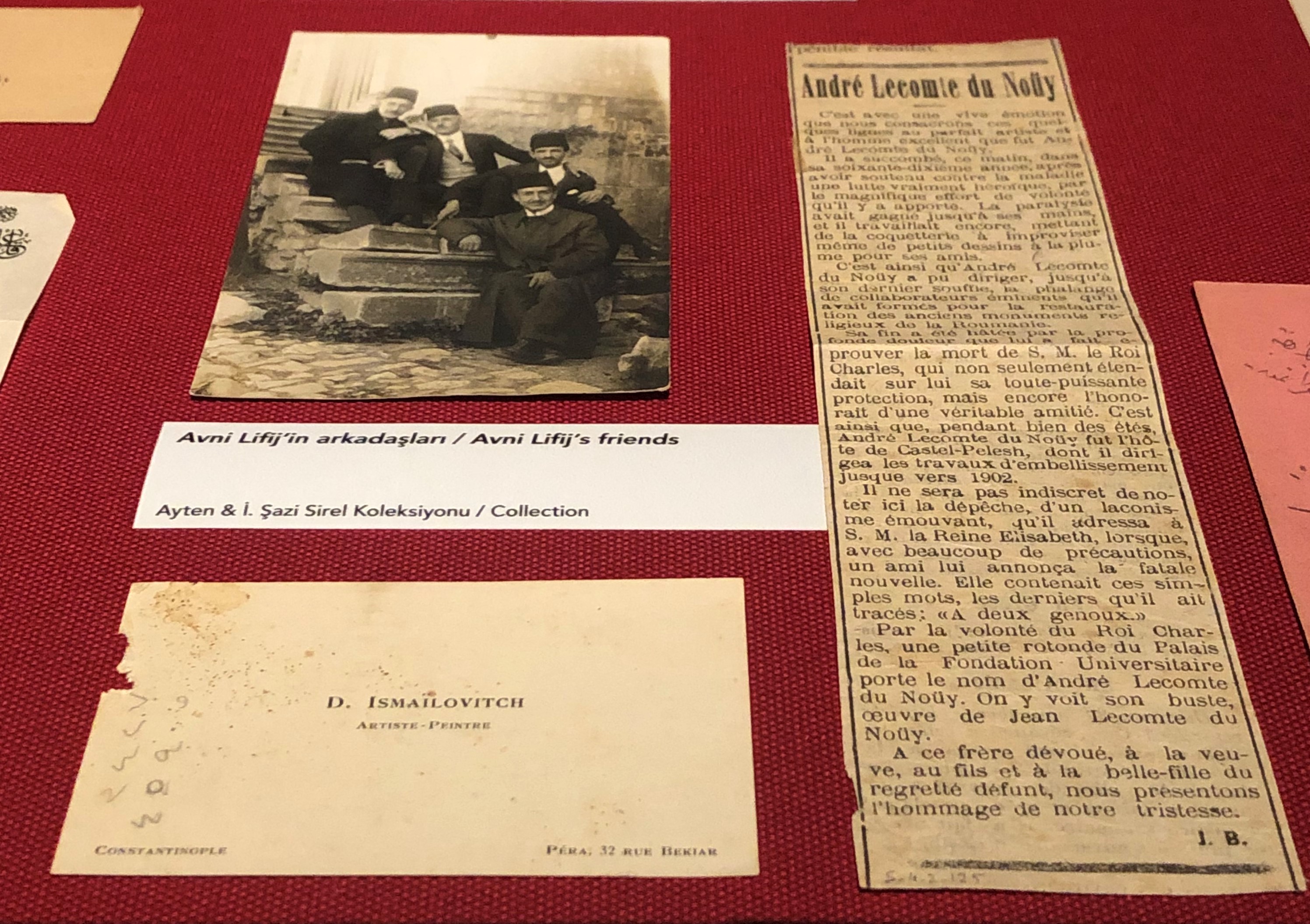

Ekaterina Aygün chanced upon Dimitri Ismailovitch's visiting card at the Avni Lifij exhibition in Istanbul. This is further evidence of contact between Ismailovitch and Turkish painters (Photo: Ekaterina Aygün, 2019).

The Piyale Pasha Mosque (was designed by Mimar Sinan and rebuilt in the mid. of the 19th century) was depicted by Dimitri İsmailovitch and Alexis Gritchenko in 1920 (Photo: Ekaterina Aygün, 2021). Anonymous. “Hudojestvennaya Vystavka.” Presse du Soir, 19 November 1921, p. 4.

Anonymous. “Vystavka Kartin Ismailovitcha.” Presse du Soir, 21 November 1921, p. 4.

Anonymous. “Vystavka Soyuza Russkih Hudojnikov.” Presse du Soir, 19 June 1922, n.p.

Anonymous. “Otkrytiye Vizantiyskoy Freski.” Presse du Soir, 2 November 1922, p. 3.

Bournakine, Anatoliy, editor. Russkiye na Bosfore. Les Russes sur le Bosphore. Imp. L. Babok & fils, 1928.

Cardoso, Rafael. Modernity in black and white: art and image, race and identity in Brazil, 1890-1945. Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Gritchenko, Alexis. İstanbul’da İki Yıl 1919–1921 – Bir Ressamın Günlüğü. Translated by Ali Berktay, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2020.

Hisamutdinov, A. “Russkiye v Brazilii.” Latinskaya America, no. 9, 2005, n.p., http://www.ilaran.ru/?n=122. Accessed 12 August 2020.

Leykind, Oleg, et al. Hudojniki Russkogo Zarubej’ya (1). Izd.dom “Mir”, 2019, p. 576.

Pereleshin, V. “Zamechatel’niy Russkiy Hudojnik.” Russkaya Mysl' (Paris), 18 November 1976, n.p.

Podzemskaia, N. “À propos des copies de la peinture byzantine à Istanbul: les artistes émigrés et l’Institut byzantin d’Amérique.” Histoire de l’art, no. 44, 1999, pp. 123–140.

Vzdornov, Gerol’d. “Russkiye hudojniki i vizantiyskaya starina v Konstantinopole.” Tvorchestvo, no. 2, 1992, pp. 30–32.

Word Count: 173

Private Archive of Dimitri Ismailovitch that belongs to Eduardo Mendes Cavalcanti (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil).

Archives & Special Collections, The College of the Holy Cross (Worcester, Massachusetts).

Istanbul Çelik Gülersoy Library.

Slavonic Library (Slovanská knihovna) in Prague.

Word Count: 38

I wish to express my most sincere gratitude to Eduardo Mendes Cavalcanti for his valuable assistance. I am also very grateful to the representatives of the Archives & Special Collections at the College of the Holy Cross (Worcester, Massachusetts) for their enormous help. Finally I would like to thank Rafael Cardoso without whose support this entry would not have been the way it is now.

Word Count: 65

Istanbul, Ottoman Empire/Turkey (1919–1927); Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (1927–1976).

Bursa Street 40 (now Sadri Alışık 40), Beyoğlu, Istanbul (studio); Küçük Yazıcı 4 (now presumably Tarlabaşı Blv. 79), Hüseyinağa, Beyoğlu, Istanbul (studio); Bekiar sokak 32 (now presumably Bekar sokak 32a), Beyoğlu, İstanbul (residence); R.O.S., Telgraf Street 15 (now presumably Tel Sokak 19), Beyoğlu (solo exhibition); Robert College (now Boğaziçi University), Bebek, Istanbul (solo exhibition).

- Istanbul

- Ekaterina Aygün. "Dimitri Ismailovitch." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5138-10436644, last modified: 22-09-2021.

-

Alexis GritchenkoPainterArt HistorianIstanbul

During the two years of his life that he spent in Istanbul, Alexis Gritchenko produced more paintings dedicated to the city than many artists produce in an entire lifetime.

Word Count: 29

Iraida BarrySculptorIstanbulAfter the Russian Revolution of 1917, Barry settled in Istanbul, where she lived until her death. She is remembered as one of the first female sculptors of the Turkish Republic.

Word Count: 29

Nikolai SaretzkiPainterGraphic ArtistIllustratorArt CriticCollectorScene DesignerIstanbulSaretzki took a rather long exile route: from the Russian Empire he fled to Istanbul, from Istanbul to Berlin, from Berlin to Prague, and from Prague to Cormeilles-en-Parisis near Paris.

Word Count: 30

Traugott FuchsPhilologistRomanistPoetPainterIstanbulTraugott Fuchs was a multi-talented philologist, painter and poet who lived in Istanbul from 1934 until the end of his life in 1997.

Word Count: 21

Foster Waterman StearnsLibrarianDiplomatCollectorPoliticianIstanbulFoster W. Stearns not only actively supported Russian-speaking émigré artists in Istanbul but also assembled a collection of their works which has survived to this day.

Word Count: 26

Nikolai SaraphanoffPainterIllustratorIstanbulThe artist is known for his numerous works with views of Istanbul, the design of the famous almanac’s cover, and the creation of decorative panels. Alas, his artistic activities were interrupted by his imprisonment.

Word Count: 35

Roman BilinskiPainterSculptorCollectorArt restorerIstanbulAt the beginning of the 1920s, a member of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, Roman Bilinski was known as a sculptor. At the end of the 1920s–beginning of the 1930s – as a sculptor, painter and connoisseur of local antiques.

Word Count: 42

Les Russes sur le BosphoreAlmanacIstanbulThe almanac Les Russes sur le Bosphore is a joint work of Russian-speaking émigrés in Istanbul who were faced with the challenge of leaving the country or becoming naturalised.

Word Count: 30

Russkiy v Konstantinopole/Le Russe à ConstantinopleGuide-bookIstanbulThe guide-book was created for Russian-speaking refugees who had to leave their country and settle in Constantinople.

Word Count: 17

First Russian émigré artists in Istanbul exhibitionExhibitionIstanbulThe first Russian-speaking émigré artists in Istanbul exhibition was a one-day event but its success led to the formation of the Union and paved the way for other exhibitions.

Word Count: 29

Exhibition of Russian émigré artists at Taksim Military BarracksExhibitionIstanbulThe exhibition of Russian-speaking émigré artists at Taksim Military Barracks was the first major exhibition organised by the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople.

Word Count: 24

Union of Russian Painters in ConstantinopleAssociationIstanbulThe Union existed for less than two years but in that short space of time a tremendous amount of work was done by its members, refugees from the Russian Empire.

Word Count: 30

Konstantinopol’skiy Kommercheskiy KlubClubIstanbulKKK was probably the most popular Russian club in Beyoğlu district between 1924 and 1926. Not only Russian émigrés but also local residents could enjoy its constantly updated entertainment programme.

Word Count: 30