Archive

Nikolai Kluge

- Nikolai

- Kluge

Николай Карлович Клуге, Nicholas Kluge, Kliougé

- 09-05-1869

- Odessa (UA)

- 01-10-1947

- Istanbul (TR)

- PainterPhotographerArt restorerArchaeologistCopyist

As a non-regular employee at the Russian Archaeological Institute of Constantinople before the Russian Revolution, Nikolai Kluge was perhaps the émigré artist most familiar with Istanbul.

Word Count: 26

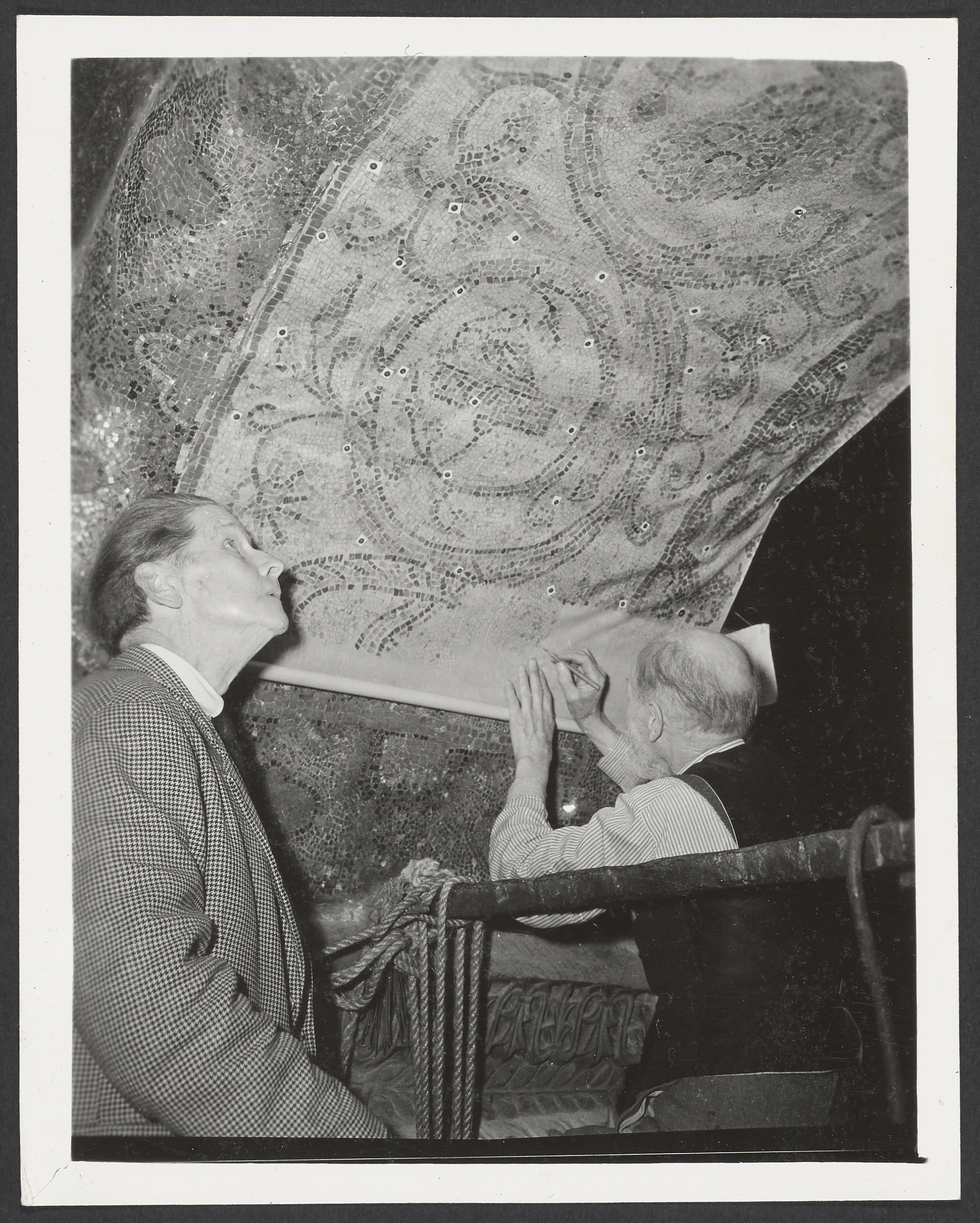

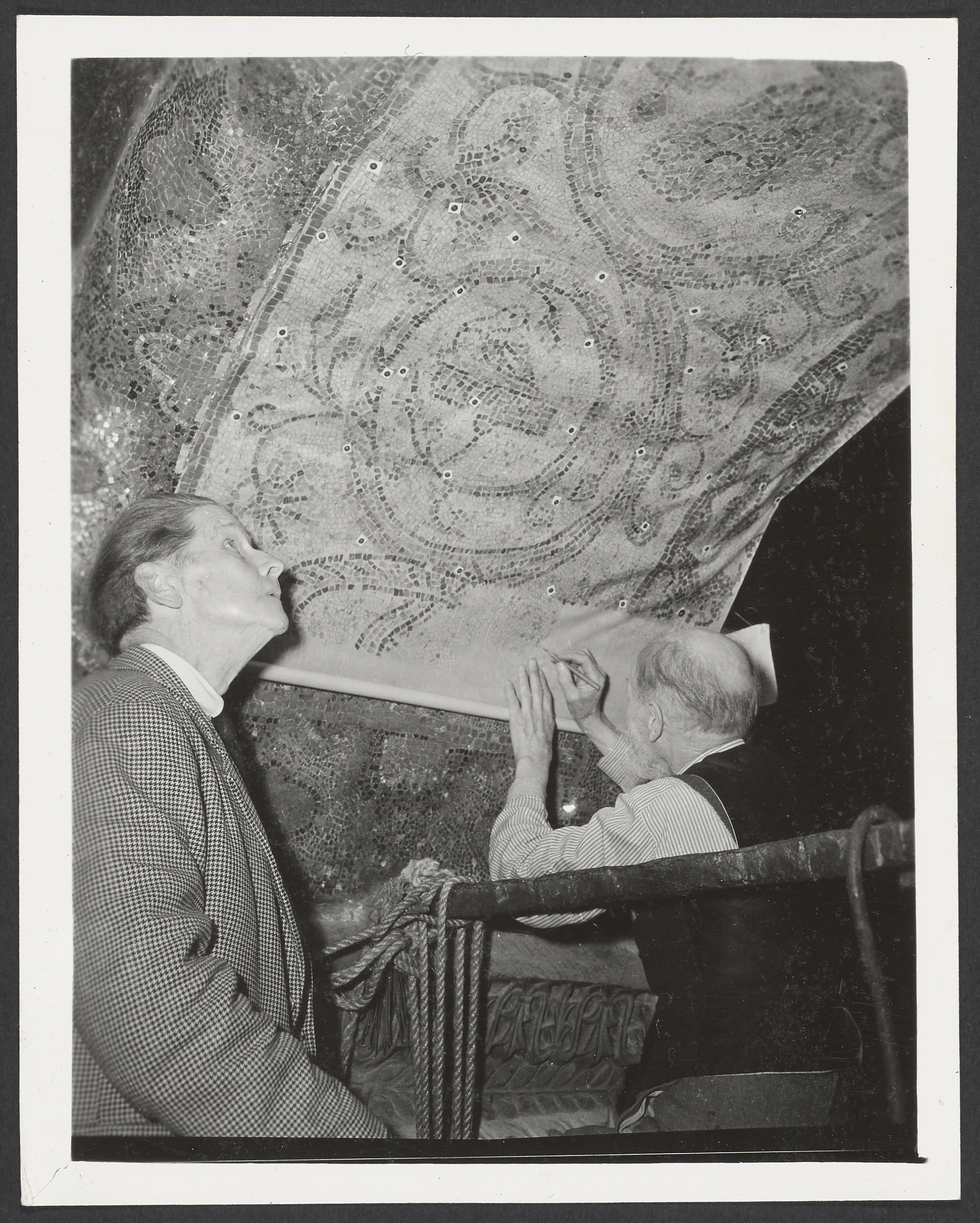

Nikolai Kluge (right) and Thomas Whittemore (left) at Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 1944. Fonds Thomas Whittemore – Institut byzantin, Subgroup 01–Series 08 (© Bibliothèque byzantine, Collège de France).

Nikolai Kluge (right) and Thomas Whittemore (left) at Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 1944. Fonds Thomas Whittemore – Institut byzantin, Subgroup 01–Series 08 (© Bibliothèque byzantine, Collège de France).

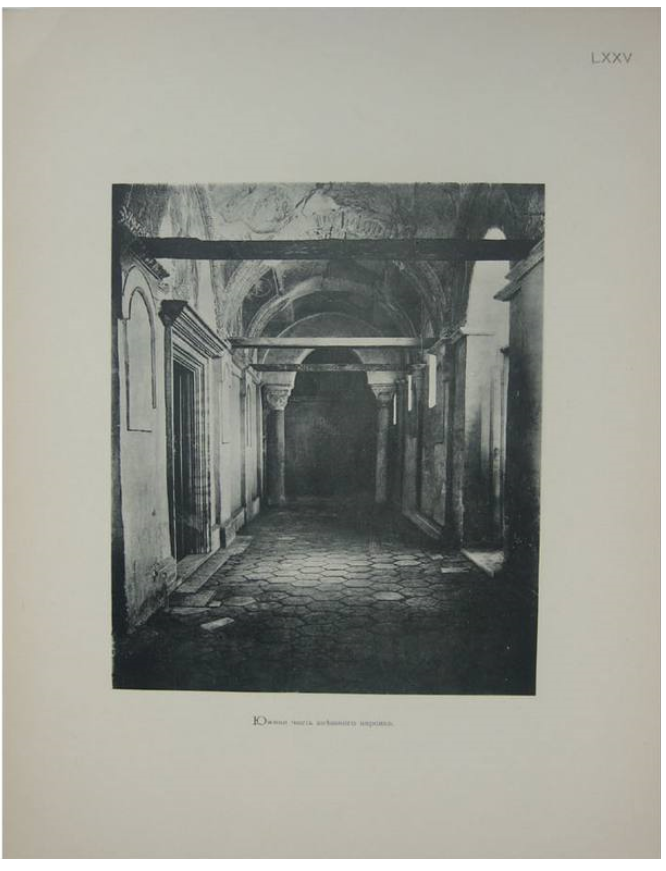

Photo by Nikolai Kluge (The title page of the publication Kariye Camii. Album for the XI volume of Izvestia of the Russian Archaeological Institute in Constantinople, Munich, 1906). Anonymous. “Lektsiya N.M. Kluge.” Presse du Soir, 8 December 1922, p. 3.

Anonymous. “Russkaya yolka na Proti.” Vecherniaia Gazeta, 16 January 1925, n.p.

Anonymous. “Nekrolog.” Russkiye Novosti (Paris), 10 October 1947, n.p.

Iodko, Olga. “Nikolai Karlovich Kluge (1869–1947) kopiist i restavrator vizantiyskih pamyatnikov.” Nemtsy v Sankt-Peterburge: Biograficheskiy aspekt XVIII–XX vv., no. X: Kunstkamera RAN, 2016, pp. 197–222. lib.kunstkamera.ru, http://lib.kunstkamera.ru/files/lib/978-5-88431-320-0/978-5-88431-320-0_13.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2020.

Levitskiy, Valeriy. “Kariye Camii.” Zarnitsy, 17 July 1921, p. 12.

Vzdornov, Gerol’d. “Russkiye hudojniki i vizantiyskaya starina v Konstantinopole.” Tvorchestvo, no. 2, 1992, pp. 30–32.

Word Count: 91

Slavonic Library (Slovanská knihovna) in Prague.

Bibliothèque byzantine, Collège de France, Paris.

Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Arşiv ve Dokümantasyon Merkezi, Istanbul.

Word Count: 25

I am grateful to Olga Iodko for her valuable comments and help. My deep gratitude also goes to Cengiz Kırlı and Mina Çakmak for making possible my work at the Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Arşiv ve Dokümantasyon Merkezi.

Word Count: 41

Istanbul, Ottoman Empire/Turkey (1920–1947).

Russian Archaeological Institute, Sakız Ağacı Street 11 (now Atıf Yılmaz Cd. 11), Hüseyinağa, Beyoğlu, Istanbul (place of work).

- Istanbul

- Ekaterina Aygün. "Nikolai Kluge." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5138-10437885, last modified: 14-09-2021.

-

Alexis GritchenkoPainterArt HistorianIstanbul

During the two years of his life that he spent in Istanbul, Alexis Gritchenko produced more paintings dedicated to the city than many artists produce in an entire lifetime.

Word Count: 29

Georges ArtemoffPainterSculptorIstanbulIt is difficult to say to what extent Istanbul was a fateful impact on Artemoff in terms of his artwork, but there he met his future wife, artist Lydia Nikanorova.

Word Count: 30

Lydia NikanorovaPainterIstanbulIn Istanbul, Nikanorova worked at copying the mosaics and frescoes of the Kariye Mosque, and met her future husband, Georges Artemoff, also an émigré artist from the former Russian Empire.

Word Count: 30

Roman BilinskiPainterSculptorCollectorArt restorerIstanbulAt the beginning of the 1920s, a member of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, Roman Bilinski was known as a sculptor. At the end of the 1920s–beginning of the 1930s – as a sculptor, painter and connoisseur of local antiques.

Word Count: 42