Archive

Rudolf Belling

- Rudolf

- Belling

- 26-08-1886

- Berlin (DE)

- 09-06-1972

- Krailling (DE)

- Sculptor

As a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts and Technical University in Istanbul from 1937 until 1966, Rudolf Belling taught his students the technicalities of form, material and proportion.

Word Count: 28

Rudolf Belling during an interview shortly after his arrival in Turkey, 1937. Yedigün, no. 212, vol. 9, March 1937, p. 8 (Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

Rudolf Belling with a student in front of copies of antique sculptures, 1937. Yedigün, no. 212, vol. 9, March 1937, p. 9 (Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

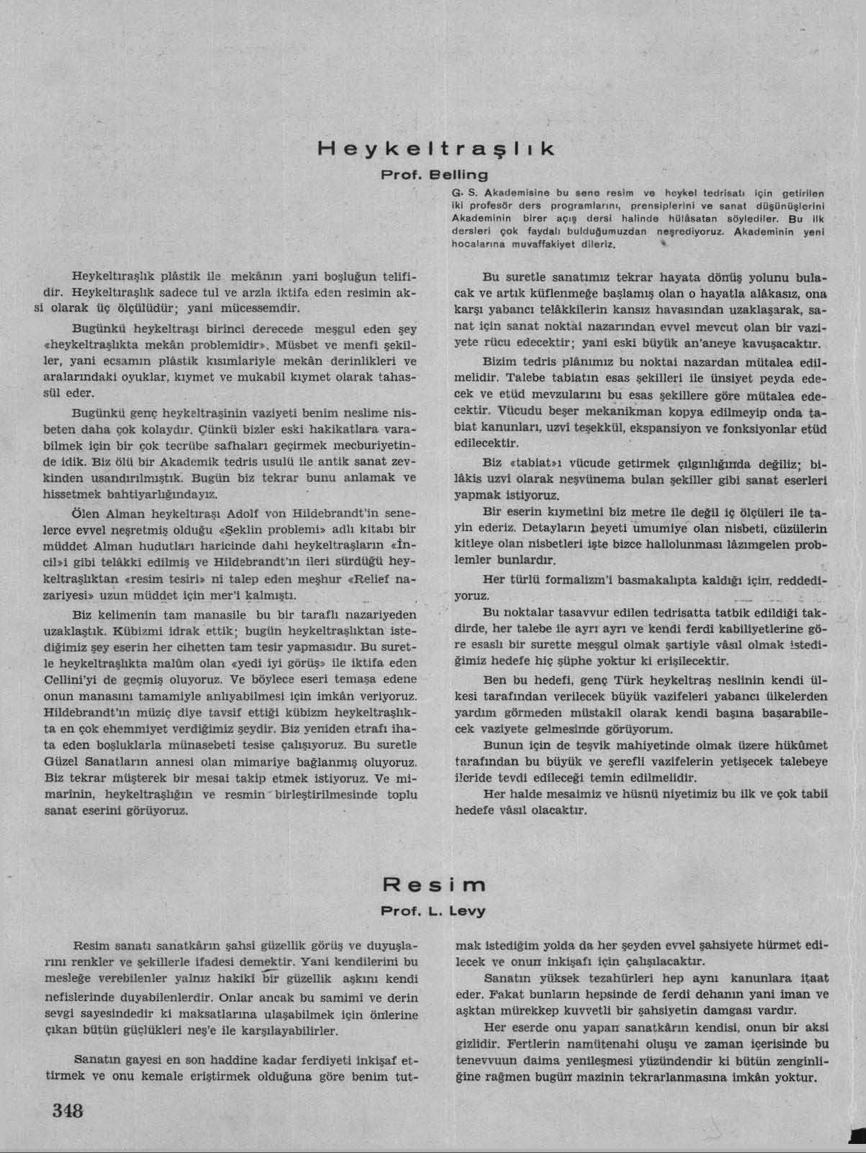

Rudolf Belling. “Heykeltraşlık.” Arkitekt, no. 12, 1936, p. 348 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr). Here, Belling explains his future teaching programme at the Academy of Fine Arts. Below, his likewise newly-appointed colleague, the French artist and professor of painting Léopold Lévy, expresses himself.

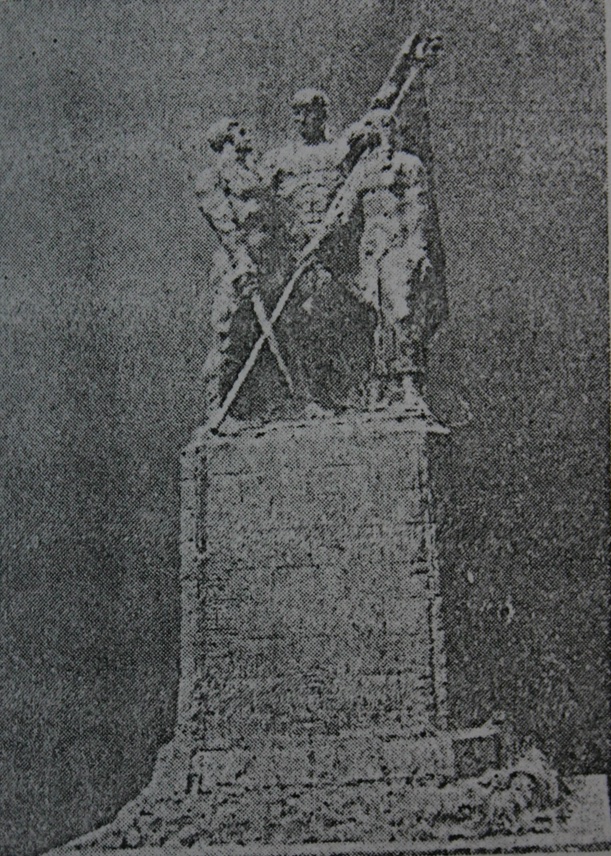

Rudolf Belling, Draft for the monument Atatürk hands over responsibility for the Republic to the youth, Istanbul University, 1938, model, second version, published in the journal Ar, no. 19, 1938, p. 8 (Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

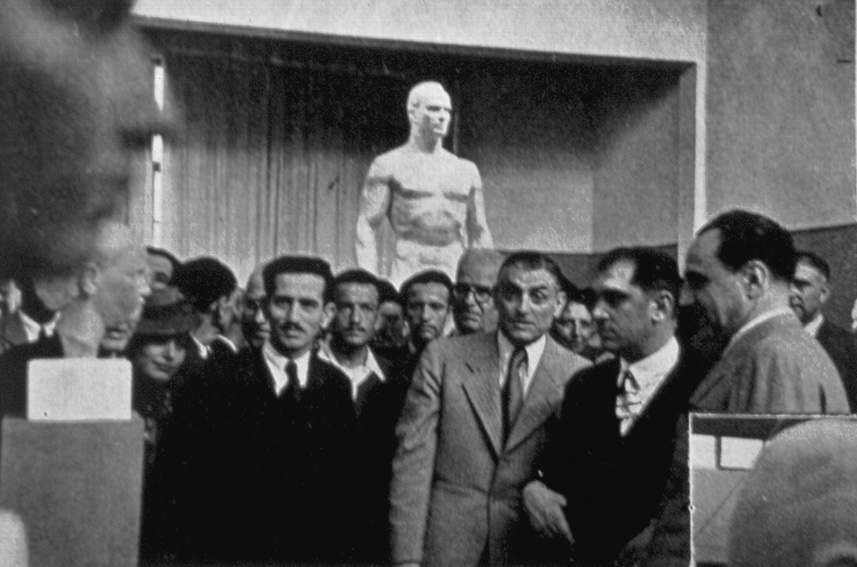

Studio exhibition class of Rudolf Belling at the Academy of Fine Arts, 1940, published in Güzel Sanatlar Dergisi, no. 4, 1942 (Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

Studio exhibition class of Rudolf Belling at the Academy of Fine Arts, 1940: Hüseyin Özkan Anka, Athlet, before 1940, published in Güzel Sanatlar Dergisi, no. 4, 1942 (Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

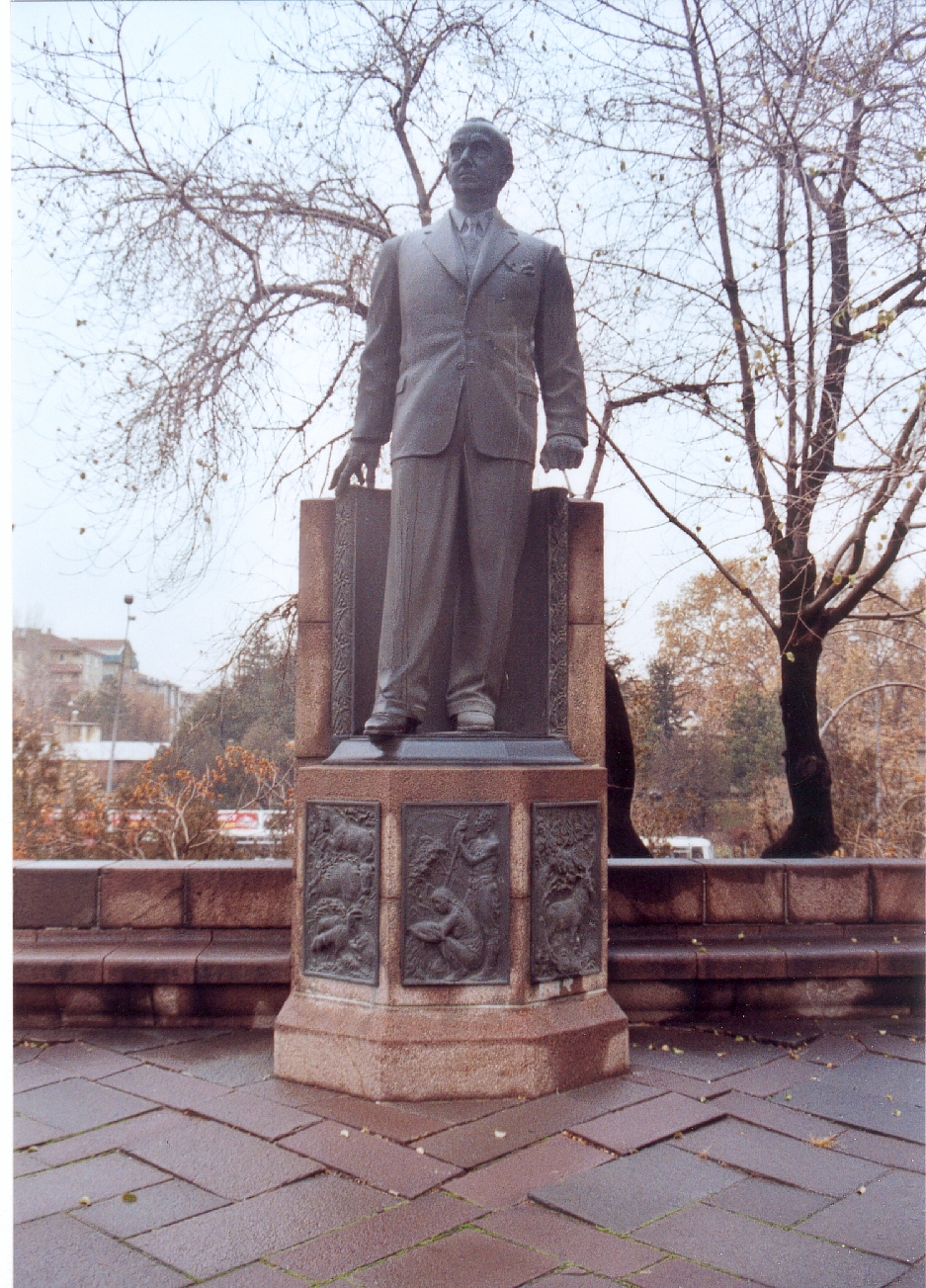

Rudolf Belling, Monument for Ismet Inönü, Courtyard of the Agricultural Faculty of the University of Ankara, 1943/44 (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2004).

Rudolf Belling with students at the Academy of Fine Arts, Istanbul, c. 1945, 1st from left: Hüseyin Gezer, photographer unknown (Rudolf-Belling-Archiv, Krailling).

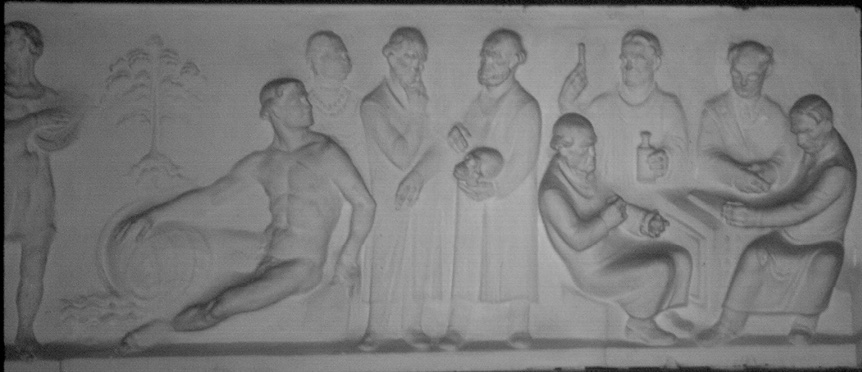

Rudolf Belling, Moulding for the Istanbul University, entrance to conference room of the Faculty of Natural Sciences, 1946, detail (Photo: Dogramaci, 2002).

Rudolf Belling, Skulptur 49 (In Memoriam Dreiklang), 1949, bronze, Collection Elisabeth Weber-Belling, Krailling (Nerdinger 1981).

Rudolf Belling, Segelmotiv, 1959/1962, Bank für Gemeinwirtschaft, Hamburg, Dornbusch/Rolandsbrücke (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2020).

Rudolf Belling, Blütenmotiv (called Schuttblume), 1967/1972, Olympiapark, Munich, (Photo: Burcu Dogramaci, 2019). Belling, Rudolf. “Heykeltraşlık.” Arkitekt, no. 12, 1936, p. 348.

Belling, Rudolf. “Bir heykel sergisi.” Güzel Sanatlar, no. 4, 1942, pp. 24–28.

Berk, Nurullah, and Hüseyin Gezer. 50 yılın Türk Resim ve Heykeli. Iş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 1973.

Berksoy, Funda, “Rudolf Belling and his contribution to Turkish sculpture.” Turcica, no. 35, 2003, pp. 165–212.

Borchhardt, Jürgen. “Bildhauer aus Österreich und Deutschland im Dienste Mustafa Kemal Pasas. Adolf Treberer-Treberspurg in der Türkei mit Anton Hanak, Heinrich Krippel, Josef Thorak und Rudolf Belling.” Adolf Treberer-Treberspurg – Ein Bildhauer zwischen den Zeiten, edited by Martin Treberspurg and Peter Bogner, exh. cat. Künstlerhaus Wien, Vienna, 2011, pp. 114–158.

Çetintaş, Vildan. Belling ve atölyesi (PhD thesis). Hacettepe University, Ankara, 2003.

Dogramaci, Burcu. Kulturtransfer und nationale Identität. Deutschsprachige Architekten, Stadtplaner und Bildhauer in der Türkei nach 1927. Gebr. Mann, 2008.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Die zwiespältige Rezeption eines Bildhauers. Rudolf Belling und seine Plastik ‘Dreiklang’ von 1919.” Das verfemte Meisterwerk. Schicksalswege moderner Kunst im “Dritten Reich” (Schriften der Forschungsreihe “Entartete Kunst”, 4), edited by Uwe Fleckner, Akademie, 2009, pp. 307–335.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Das Atatürk-Mausoleum in Ankara. Paul Bonatz, Rudolf Belling und die Genese eines türkischen Nationaldenkmals.” Im Dienst der Nation. Identitätsstiftungen und Identitätsbrüche in Werken der bildenden Kunst (Mnemosyne. Schriften des Warburg-Kollegs), edited by Matthias Krüger and Isabella Woldt, Akademie, 2011a, pp. 309–324.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Keine Rückkehr nach Berlin. Die Emigranten Martin Wagner und Rudolf Belling in der Nachkriegszeit.” Verfolgt und umstritten! Remigrierte Künstler im Nachkriegsdeutschland, edited by Michael Grisko and Henrike Walter, Peter Lang, 2011b, pp. 197–212.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “‘Gegenständlich und naturfern zugleich’. Von Denkmälern und freien Formen: Rudolf Belling in Istanbul und München.” Rudolf Belling: Skulpturen und Architekturen, edited by Dieter Scholz and Christina Thomson, exh. cat. Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, 2017, pp. 286–303.

Kandemir, Feridun. “Güzel Sanatlar Akademisinde Iki Sanatkârı Ziyaret.” Yedigün, no. 212, 31 March 1937, pp. 8–9.

Nerdinger, Winfried. Rudolf Belling und die Kunstströmungen in Berlin 1918–1923. Mit einem Katalog der plastischen Werke. Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1981.

Schubert, Dirk. Hamburger Wohnquartiere. Ein Stadtführer durch 65 Siedlungen. Dietrich Reimer, 2005, pp. 254–257.

Schumann, Georg, President of the Akademie der Künste, to Rudolf Belling (Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Historical Archive, 8 July 1937).

Word Count: 360

Rudolf-Belling-Archiv, Krailling, http://rudolfbelling.com.

Akademie der Künste, Historical Archive, Berlin.

Word Count: 12

My deep gratitude goes to Elisabeth Weber-Belling, who constantly supported my research.

Word Count: 12

Istanbul, Turkey (1937–1966).

Kristina Apartmanı, Mete Caddesi No. 24, Gümüşsuyu, Istanbul (residence, 1937–c.1953); Bağ Odaları Sokak 3/5, (now Prof. Dr. Tarık Zafer Tunaya Sokak No. 3), Gümüşsuyu, Istanbul (residence, 1953–1966).

- Istanbul

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Rudolf Belling." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5138-9616505, last modified: 18-09-2021.

-

Jules KanzlerPainterPhotographerIstanbul

Kanzler spent part of his life in the Russian Empire as a painter and the other in Turkey as a photographer who “documented” the early years of the Turkish Republic.

Word Count: 30

KenanFashion IllustratorGraphic ArtistIstanbulThe Turkish graphic designer Kenan was a popular artist in the Weimar Republic. He returned to Istanbul in 1943 to take up a position at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Word Count: 29

Gustav OelsnerArchitectCity PlannerIstanbulGustav Oelsner became the founding father of urban planning in Turkey, his country of exile. He was also the author of numerous articles for the architectural journal Arkitekt.

Word Count: 28

Roman BilinskiPainterSculptorCollectorArt restorerIstanbulAt the beginning of the 1920s, a member of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, Roman Bilinski was known as a sculptor. At the end of the 1920s–beginning of the 1930s – as a sculptor, painter and connoisseur of local antiques.

Word Count: 42

Ismet Inönü HeykeliMonumentIstanbulBetween 1941 and 1944 the Berlin sculptor Rudolf Belling worked on the Ismet Inönü Heykeli. The monument was placed in the neighbourhood of Maçka.

Word Count: 24

Park HotelHotelIstanbulPark Hotel in Ayazpaşa- Gümüşsuyu was frequented by newly-arrived emigrants. Rudolf Belling and Paul and Gertrud Hindemith stayed there before moving into more settled accommodation or leaving town.

Word Count: 31

Pera Palace HotelHotelIstanbulThe Pera Palace was the gem of Pera district where people gathered to wine and dine and be entertained, as well as to discuss the issues of the day.

Word Count: 29

ArkitektMagazineIstanbulThe architecture magazine Arkitekt was an important platform for emigrated architects and urban planners such as Bruno Taut, Martin Wagner, Wilhelm Schütte, Ernst Reuter and Gustav Oelsner.

Word Count: 28

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte ApartmentResidenceIstanbulThe exiled architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte lived from 1938 in an apartment in Kabataş, on the European side of Istanbul. The flat has been preserved in numerous photographs, allowing the interior design to be reconstructed. The view of the Bosporus from the balcony was spectacular.

Word Count: 48

Mimarî BilgisiBookIstanbulThe architect Bruno Taut published his textbook Mimarî Bilgisi in 1938, only two years after his emigration to Istanbul, where he was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Word Count: 29

Türk Tarih SergisiExhibitionIstanbulIn 1937, the exiled urban planner Martin Wagner was commissioned to design an exhibition for a congress of the Association for the Study of Turkish History at Dolmabahçe Palace.

Word Count: 29