Archive

Arkitekt

- Magazine

- Arkitekt

- Zeki SayarAbidin MortaşSedad Hakkı Eldem

- 1931

- 1980

Anadolu Han (today Arpacılar Cad. No. 6), Eminönü, Istanbul (editorial office).

- Turkish

- Istanbul (TR)

The architecture magazine Arkitekt was an important platform for emigrated architects and urban planners such as Bruno Taut, Martin Wagner, Wilhelm Schütte, Ernst Reuter and Gustav Oelsner.

Word Count: 28

Arkitekt, no. 9, 1936, cover (Photo: Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

Arkitekt, no. 1–2, 1939, cover (Photo: Archive Burcu Dogramaci).

Arkitekt, no. 10–11, 1936, cover. Issue with the essay “Istanbul havalisinin plânı” by Martin Wagner (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

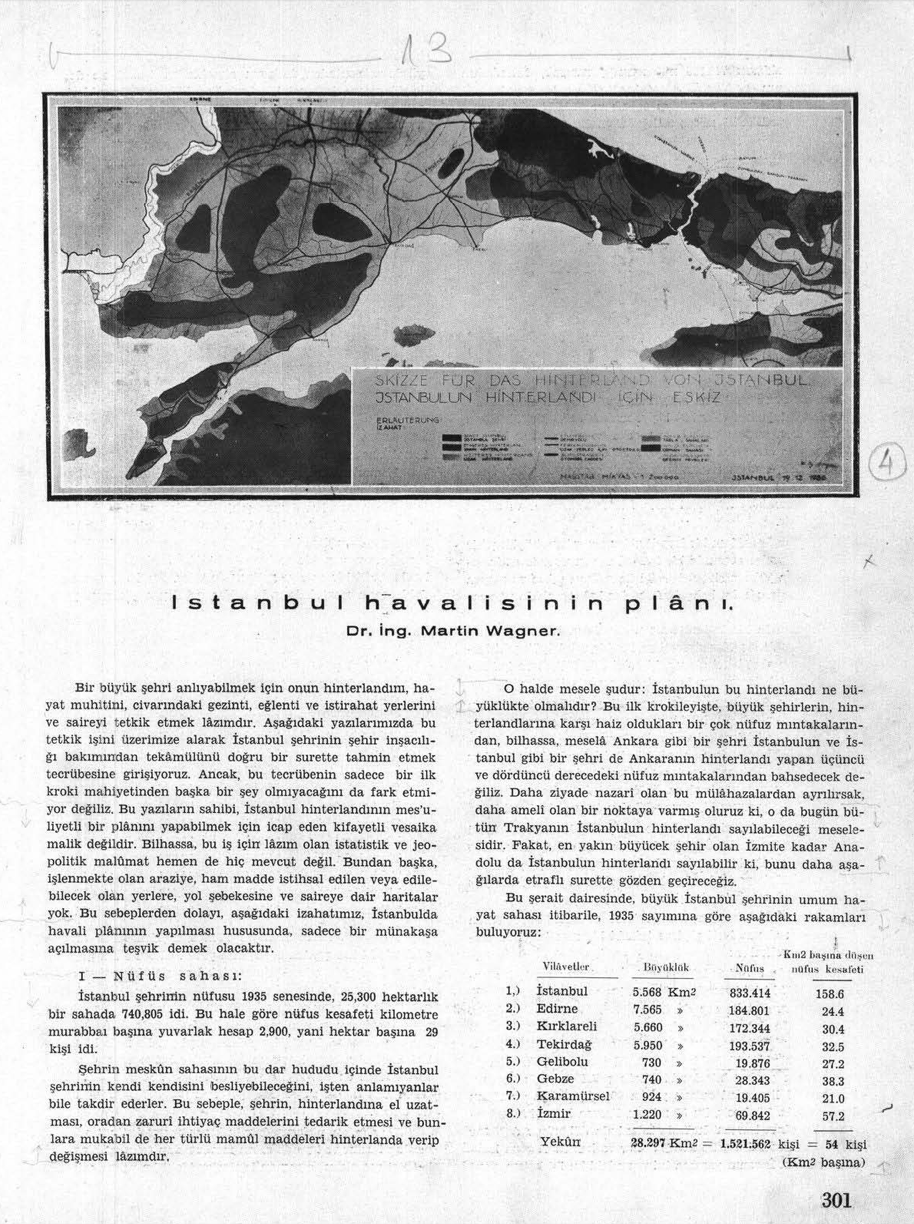

Martin Wagner. “Istanbul havalisinin plânı.” Arkitekt, no. 10–11, 1936, p. 301 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Arkitekt, no. 7, 1938, cover. Issue featuring the essay “Proporsyon” by Bruno Taut (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Bruno Taut. “Proporsiyon.” Translation Adnan Kolatan. Arkitekt, no. 7, 1938, p. 194 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Arkitekt, no. 3–4, 1941, cover. Issue featuring Wilhelm Schütte’s essay “Sefalet Mahalleleri” (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Wilhelm Schütte. “Sefalet Mahalleleri.” [Neighbourhoods of Misery] Translation Adnan Kolatan. Arkitekt, no. 3–4, 1941, p. 78 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Arkitekt, no. 5–6, 1943, cover. Issue with Ernst Reuter’s essay “Kasabalarimiz“ and Wilhelm Schütte’s contribution “Karl Friedrich Schinkel” (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Ernst Reuter. “Kasabalarimiz.“ [Our villages] Translation Adnan Kolatan. Arkitekt, no. 5–6, 1943, p. 121 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Gustav Oelsner. “Şehircilikte Abidevlik.” [Monuments in City planning] Translation Halet Çambel. Arkitekt, no. 11–12, 1945, p. 265. Arkitekt/Mimar, 1931–1980.

Arsebük, Güven, et al., editors. Light on Top of the Black Hill. Studies presented to Halet Çambel = Karatepe’deki Isik. Halet Çambel’e sunulan yazilar. Ege Yayınları, 1998.

Akay, Zafer. “Arkitekt'in 50 Yılı: Evreler, yazarlar, Mimarlar.” Zeki Sayar ve Arkitekt: tasarlamak, örgütlemek, belgelemek, edited by Ali Cengizkan et al., TMMOB Mimarlar Odası, 2015, pp. 149–158.

Cengizkan, Ali, et al, editors. Zeki Sayar’a armağan: Türkiye Mimarlığı ve Eleştiri. TMMOB Mimarlar Odası, 2012.

Cengizkan, Ali, et al., editors. Zeki Sayar ve Arkitekt: tasarlamak, örgütlemek, belgelemek. TMMOB Mimarlar Odası, 2015.

mimar.ist, vol. 12, no. 46, 2012.

Sayar, Zeki. “No title.” Anılarda Mimarlık. Yemyapı, 1995, pp. 100–113.

Word Count: 107

Word Count: 5

I would like to thank Ali Cengizkan, who helped with information. The digital issues of Arkitekt magazine on the Mimarlar Odası website were an important source for this entry.

Word Count: 29

- Istanbul

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Arkitekt." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5140-10801463, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

Rudolf BellingSculptorIstanbul

As a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts and Technical University in Istanbul from 1937 until 1966, Rudolf Belling taught his students the technicalities of form, material and proportion.

Word Count: 28

Gustav OelsnerArchitectCity PlannerIstanbulGustav Oelsner became the founding father of urban planning in Turkey, his country of exile. He was also the author of numerous articles for the architectural journal Arkitekt.

Word Count: 28

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte ApartmentResidenceIstanbulThe exiled architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte lived from 1938 in an apartment in Kabataş, on the European side of Istanbul. The flat has been preserved in numerous photographs, allowing the interior design to be reconstructed. The view of the Bosporus from the balcony was spectacular.

Word Count: 48

Mimarî BilgisiBookIstanbulThe architect Bruno Taut published his textbook Mimarî Bilgisi in 1938, only two years after his emigration to Istanbul, where he was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Word Count: 29

Türk Tarih SergisiExhibitionIstanbulIn 1937, the exiled urban planner Martin Wagner was commissioned to design an exhibition for a congress of the Association for the Study of Turkish History at Dolmabahçe Palace.

Word Count: 29

Mehmet Cemil CemDiplomatCaricaturistIstanbulCemil Cem is remembered as a cartoonist, although he also managed the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul for four years. While director of the academy, he supported Russian-speaking artists.

Word Count: 30

Ragıp Devres VillaBuildingResidenceIstanbulThe house designed by the Swiss-Austrian architect Ernst Egli for the engineer Ragip Devres in Istanbul Bebek left its mark on the Turkish villa landscape.

Word Count: 25

Bruno Taut HouseResidenceIstanbulArchitect Bruno Taut’s house in Ortaköy stands on a hillside with a panoramic view of the Bosporus, located at the point where Asia and Europe are closest to one another.

Word Count: 32