Archive

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte Apartment

- Residence

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte Apartment

Word Count: 8

- Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky ve Wilhelm Schütte apartmanı

- 1938

- 1944

Cili Apartman (Cili Kira evi), Izzet Paşa Sokak No. 28, Gümüşsuyu/Kabataş (now Hacı Izzet Paşa Sokak No. 18, Beyoğlu), Istanbul (residence).

- Istanbul (TR)

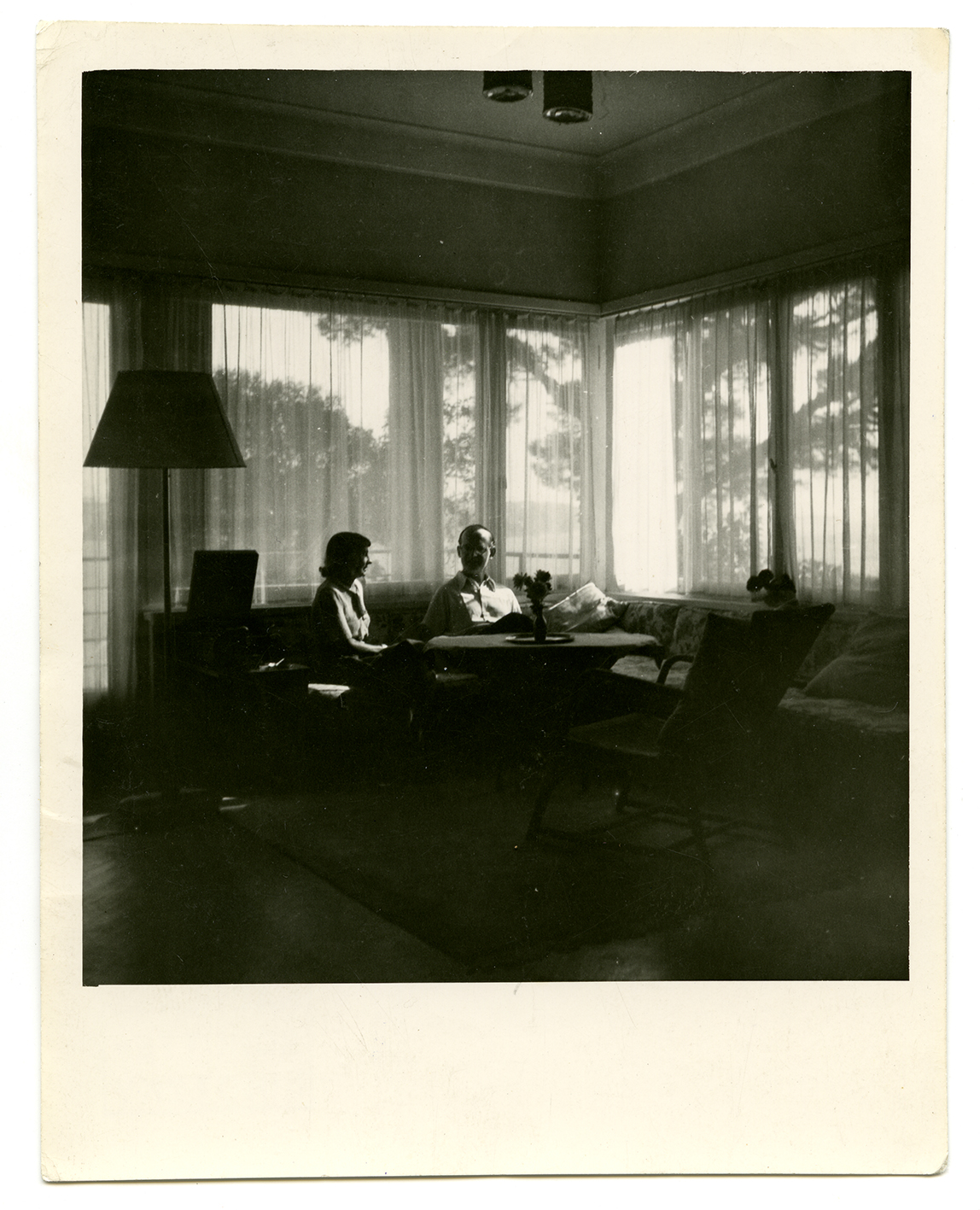

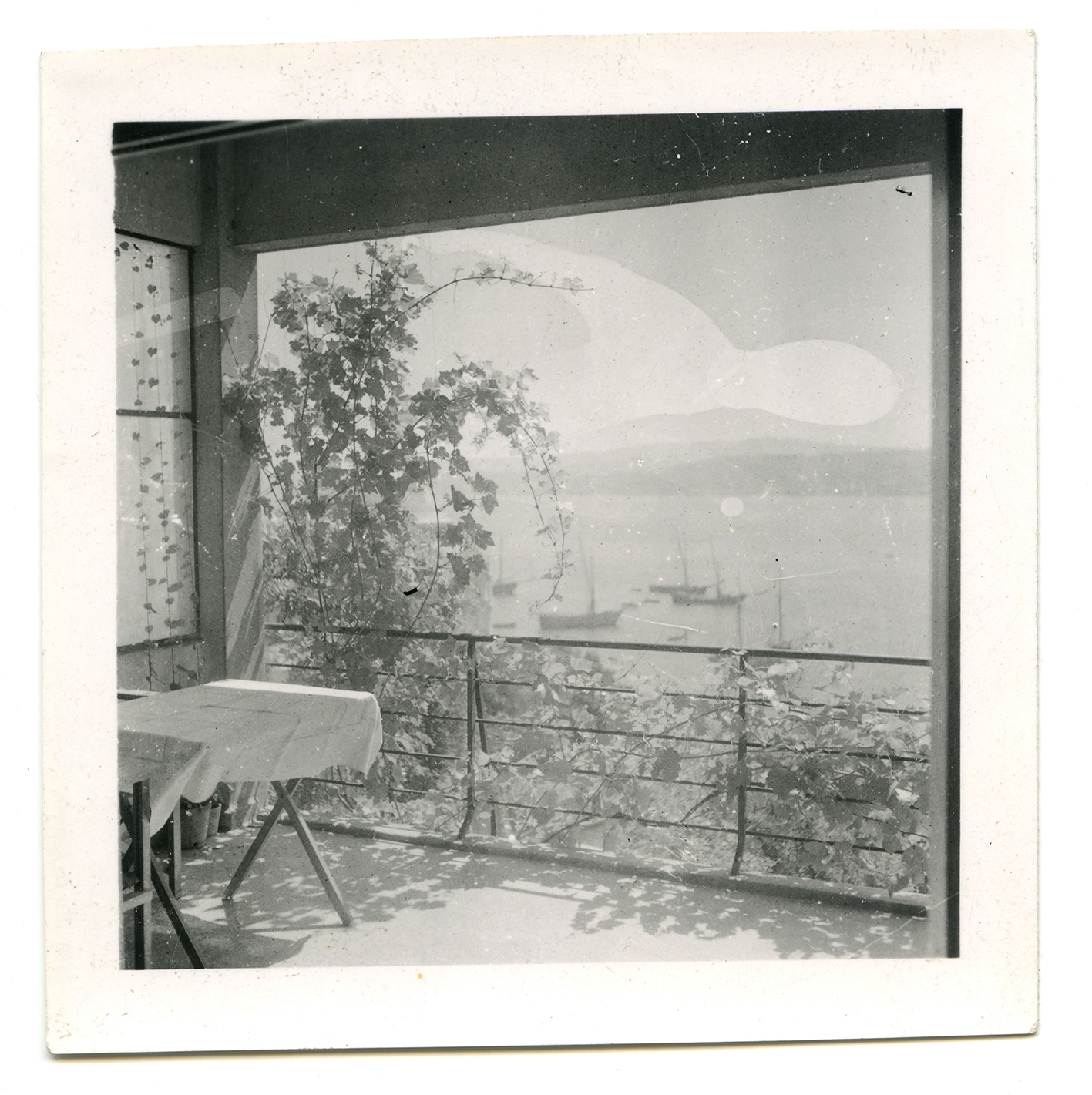

The exiled architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte lived from 1938 in an apartment in Kabataş, on the European side of Istanbul. The flat has been preserved in numerous photographs, allowing the interior design to be reconstructed. The view of the Bosporus from the balcony was spectacular.

Word Count: 48

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte on the balcony of their apartment, Cili Apartman House, Izzet Paşa Sokak No. 28, Kabataş, c. 1938, detail (ÖGFA, Archive Wilhelm Schütte).

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte on the balcony of their apartment, Cili Apartman House, Izzet Paşa Sokak No. 28, Kabataş, c. 1938 (ÖGFA, Archive Wilhelm Schütte).

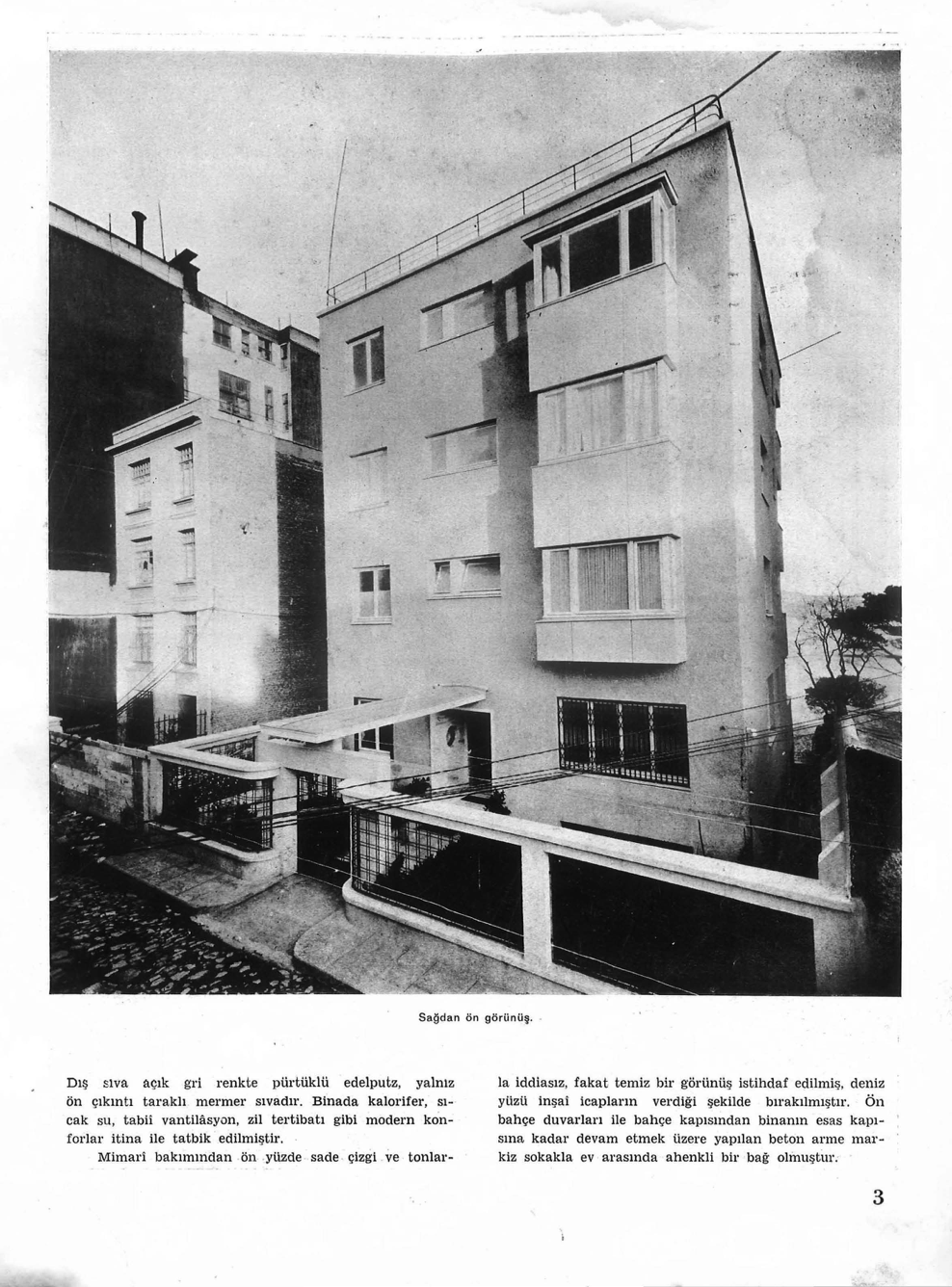

Anonymous. “‘Cili’ kira evi. Taksim. Mimar Zeki Sayâr.” Arkitekt, no. 1, 1936, p. 1: View from the street (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

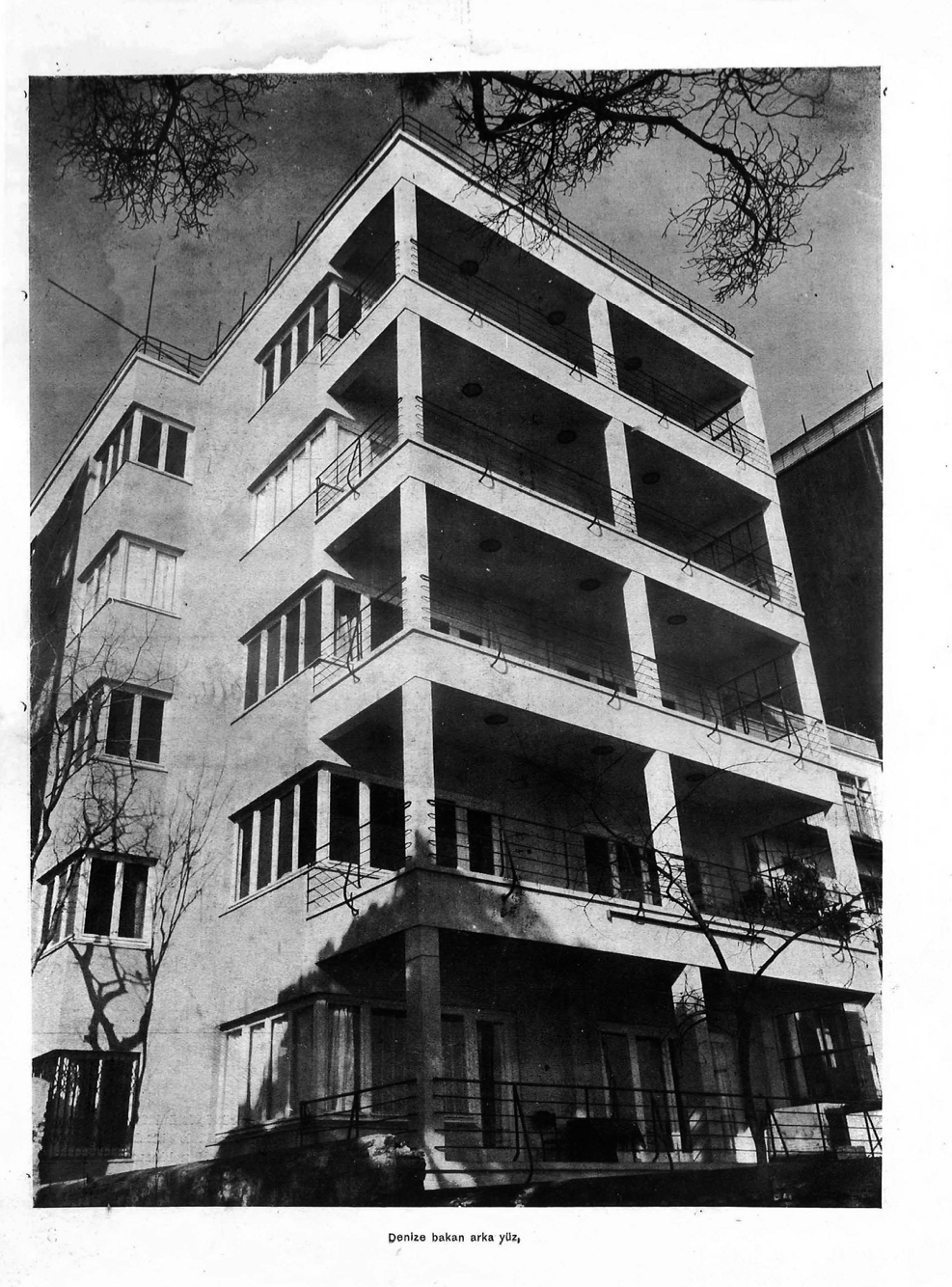

Anonymous. “‘Cili’ kira evi. Taksim. Mimar Zeki Sayâr.” Arkitekt, no. 1, 1936, p. 4: View from the street of the rear of the building, which overlooked the sea (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

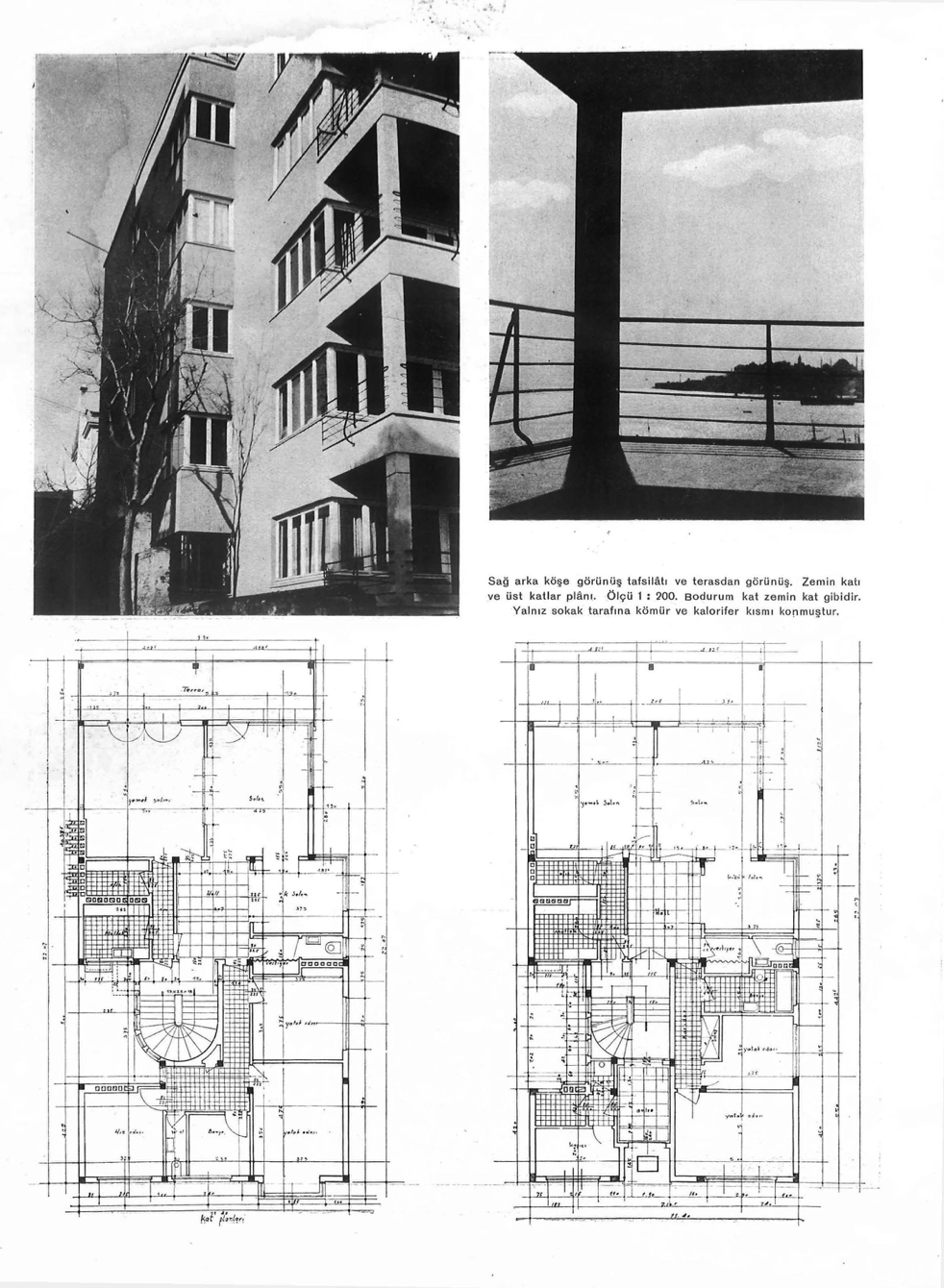

Anonymous. “‘Cili’ kira evi. Taksim. Mimar Zeki Sayâr.” Arkitekt, no. 1, 1936, p. 6 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Contemporary view of Cili Apartman House, Izzet Paşa Sokak No. 28, Kabataş, now Hacı Izzet Paşa Sokak No. 18, Beyoğlu (Photo: Thomas Flierl, 2019).

Entrance to Cili Apartman House, Izzet Paşa Sokak No. 28, Kabataş, now Hacı Izzet Paşa Sokak No. 18, Beyoğlu (Photo: Thomas Flierl, 2019).

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte in their living room, 1939, photographer unknown, 11,2 x 8,7 cm (University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive, Inv.Nr. F/151).

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and/or Wilhelm Schütte, Apartment in Istanbul, view from the balcony, c. 1939–1943, 7 x 7 cm (University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive, Inv.Nr. F/152).

Apartment in Istanbul, worktable, c. 1943, 6 x 6 cm (University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive, Inv.Nr. F/142). Wilhelm Schütte's workplace with the typewriter on which he wrote his essays for the journal Arkitekt. The photograph may have been taken by Schütte.

Apartment in Istanbul, dining area, c. 1943, 6 x 6 cm (University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive, Inv.Nr. F/147). The three prints on the wall refer to trips taken by the architects to Japan and China in the 1930s.The photograph may have been taken by Wilhelm Schütte.

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte (standing, 2nd left) in front of the school in Karapürsek, September 1938, photographer unknown (ÖGFA, Archive Wilhelm Schütte). Soon after their arrival, the two architects visited village schools in the wider vicinity of Ankara and Istanbul.

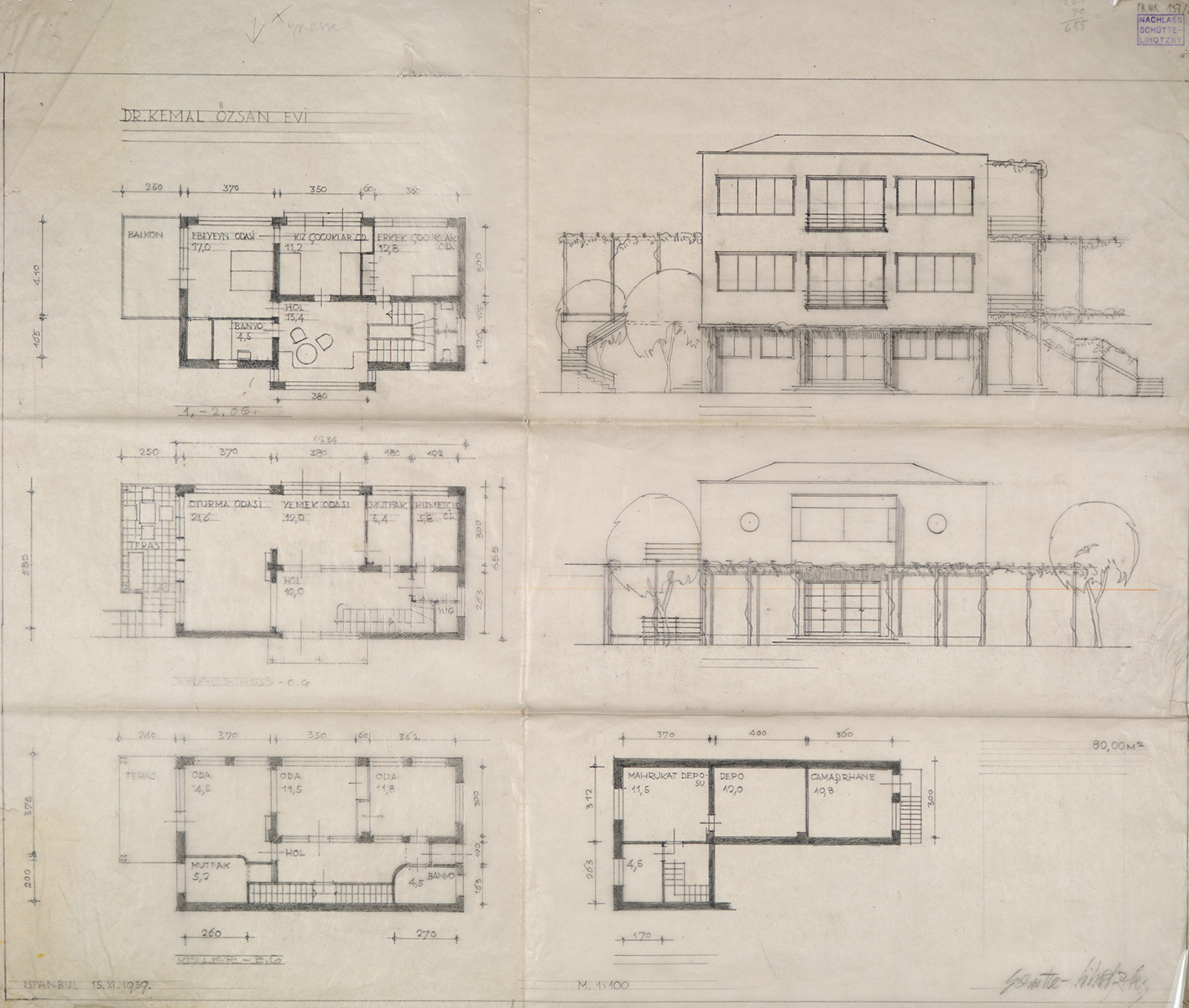

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Dr Kemal Özsan House, 1939, 51 x 43 cm (University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive, Inv.Nr. 137/2. Reproduction: Robert Newald; © Luzie Lahtinen-Stransky). The drawing shows floor plans and views of the facades. The house should have been built in Istanbul but was never realised.

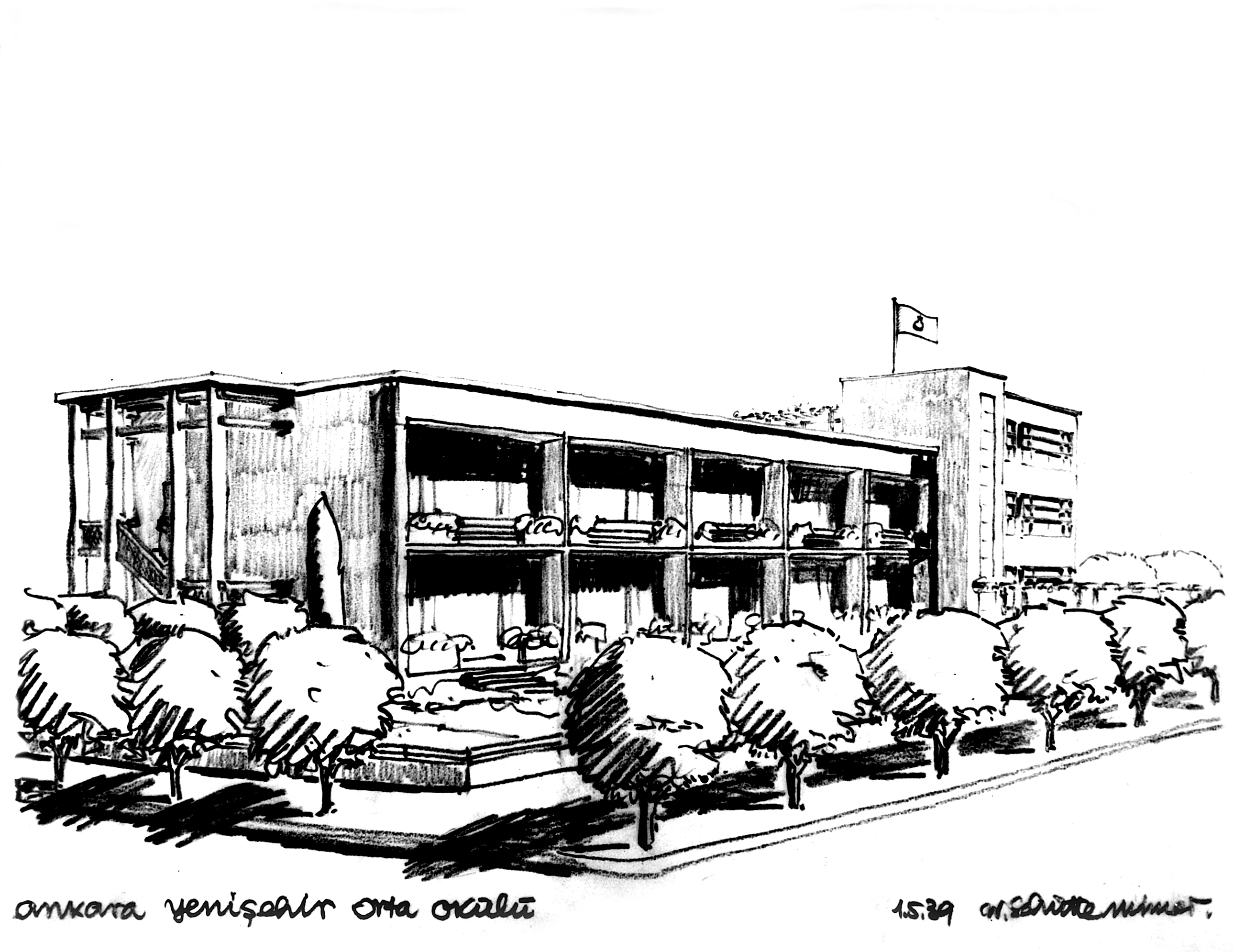

Wilhelm Schütte, Ankara Yenişehir Orta Okulu [Secondary School in Ankara Yenişehir), 1.5.1939 (ÖGFA, Archive Wilhelm Schütte).

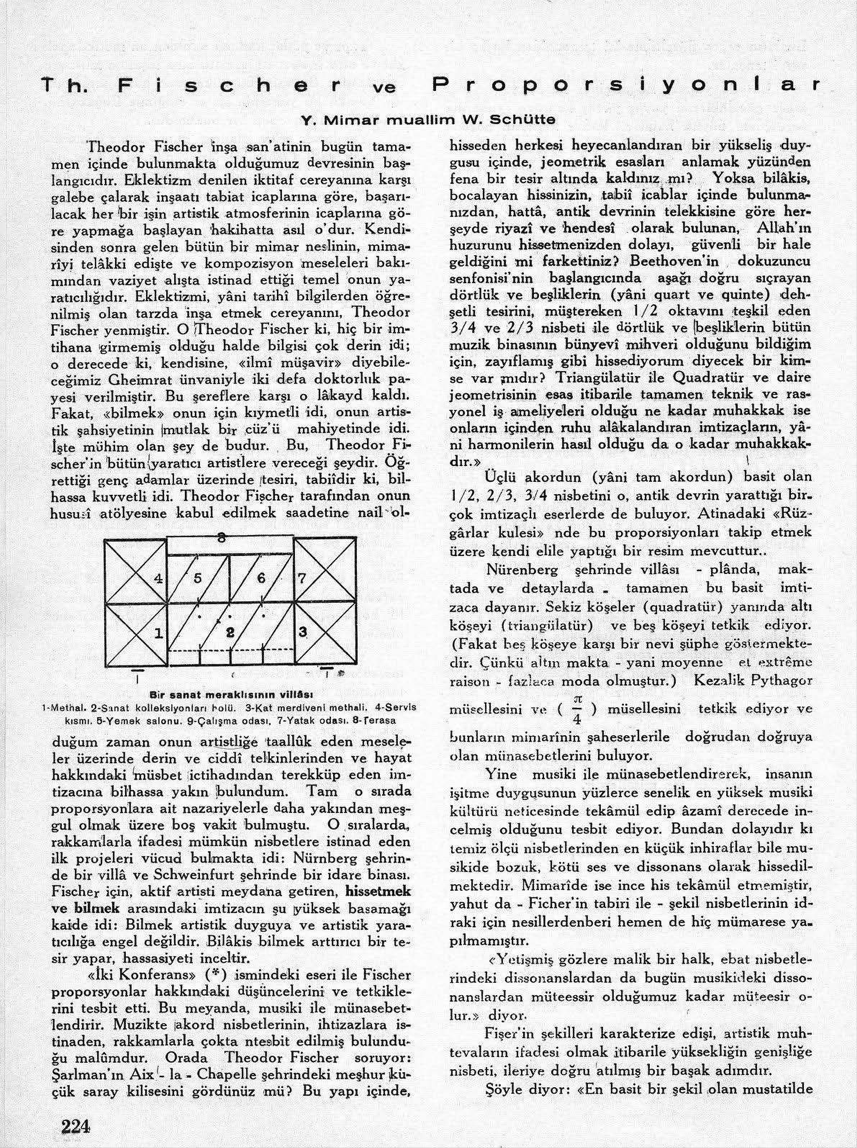

Wilhelm Schütte. “Th. Fischer ve Proporsiyonlar.” [Theodor Fischer and the proportions] Arkitekt, no. 9–10, 1940, p. 224 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

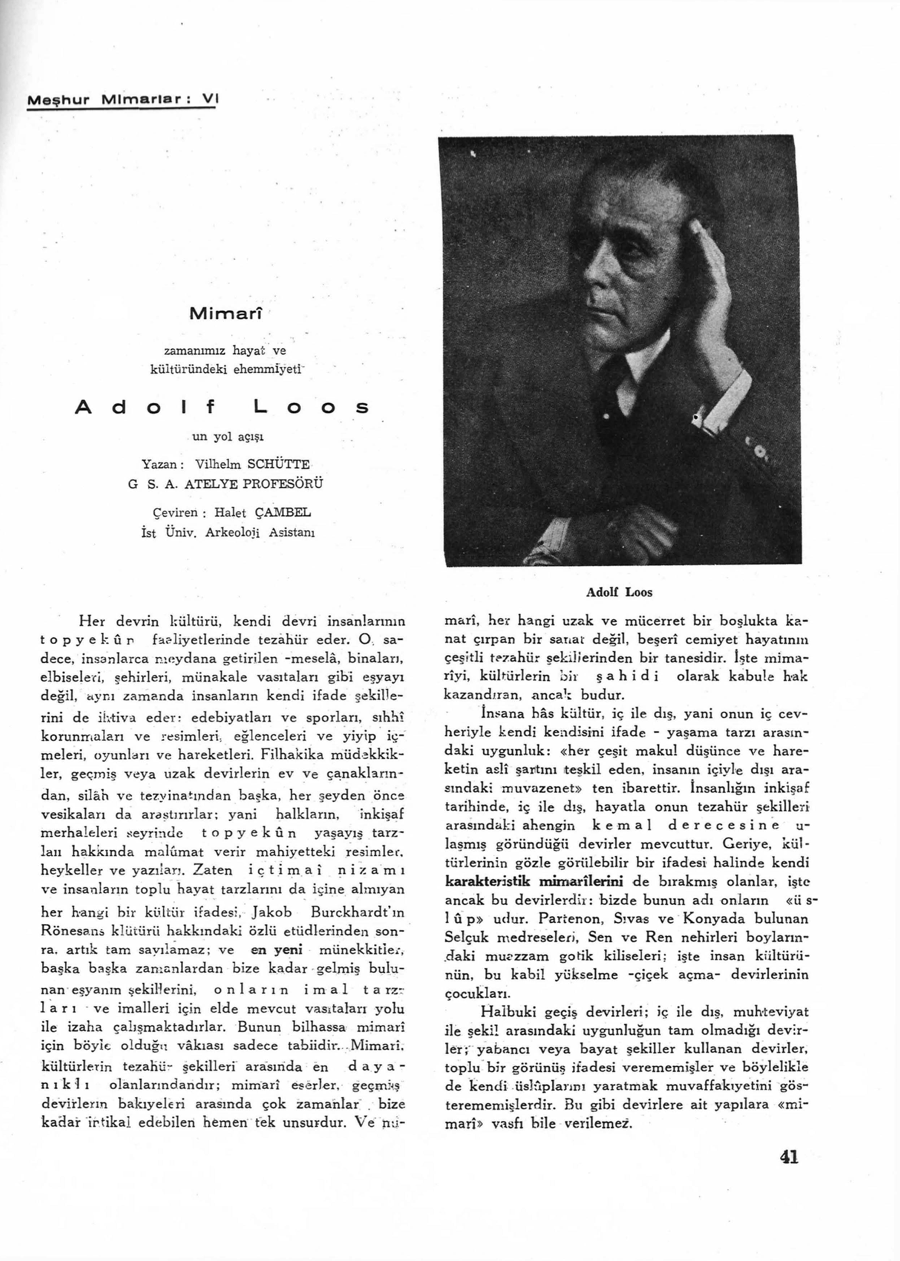

Wilhelm Schütte. “Adolf Loos.” Translation Halet Çambel. Arkitekt, no. 1–2, 1941, p. 41 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

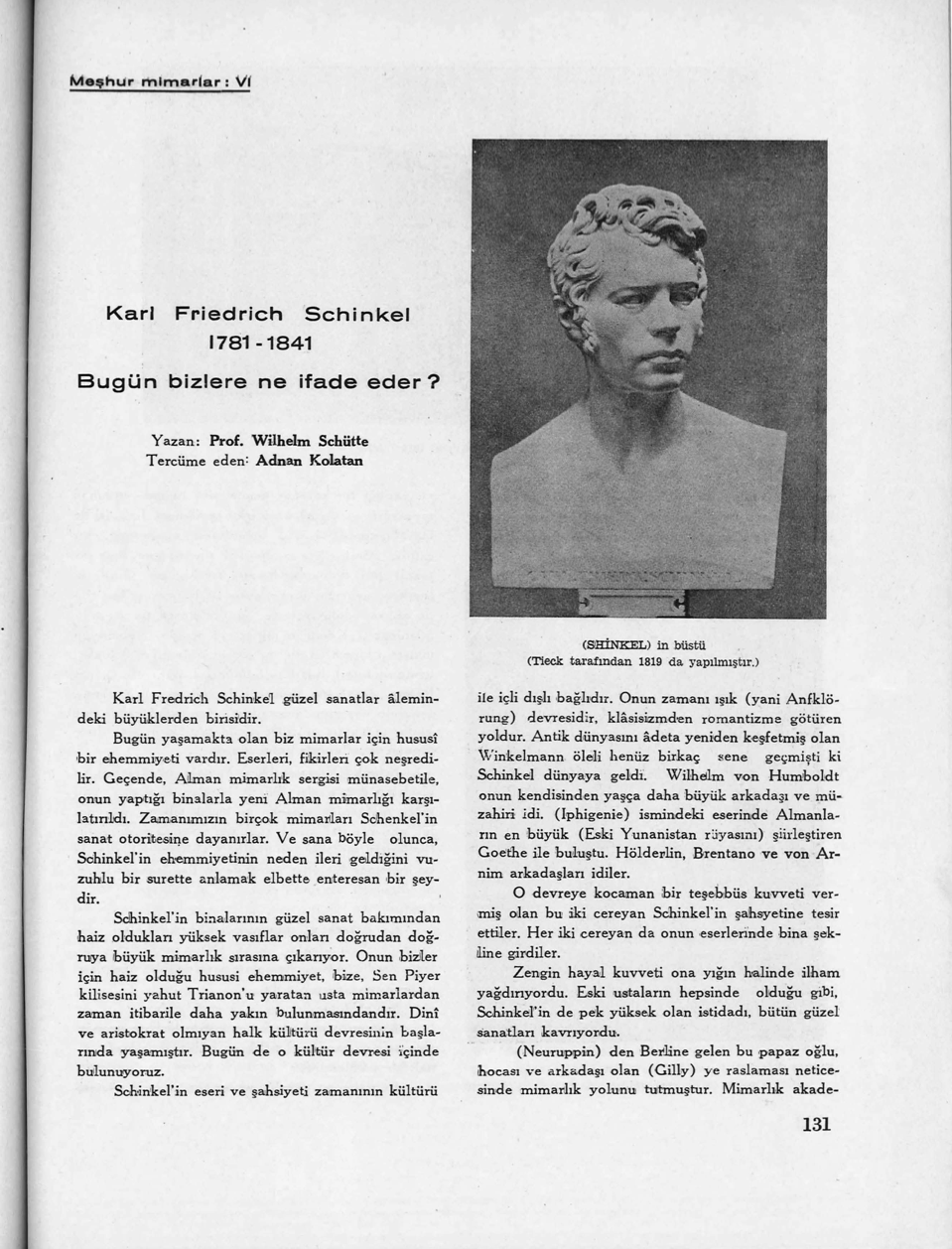

Wilhelm Schütte. “Karl Friedrich Schinkel 1781–1841. Bugün bizlere ne ifade eder?.” [Karl Friedrich Schinkel 1781–1841. What does he tell us today?] Translation: Adnan Kolatan. Arkitekt, no. 5–6, 1943, p. 131 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

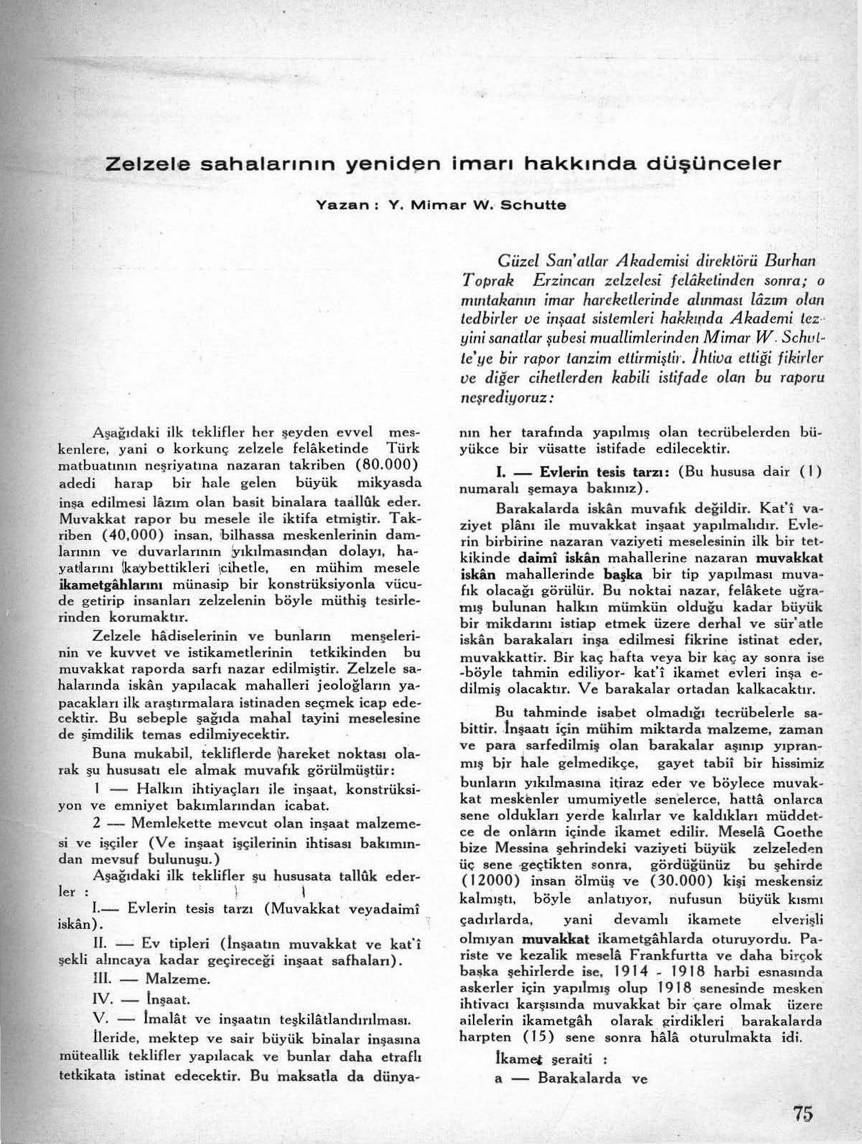

Wilhelm Schütte. “Zelzele sahalarının yeniden imari hakkında düşünceler.” [Thoughts on reconstruction in earthquake zones] Arkitekt, no. 3–4, 1940, p. 75 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

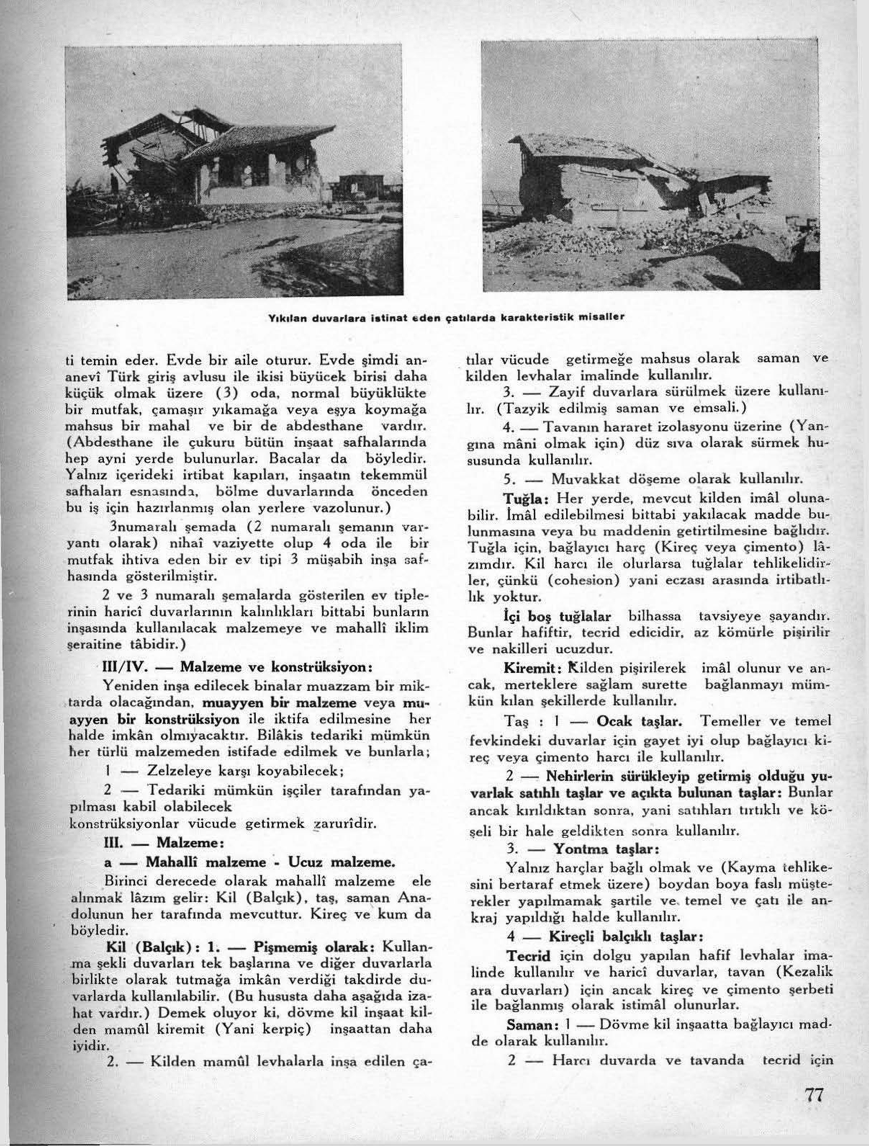

Wilhelm Schütte. “Zelzele sahalarının yeniden imari hakkında düşünceler.” [Thoughts on reconstruction in earthquake zones] Arkitekt, no. 3–4, 1940, p. 77 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr).

Wilhelm Schütte. “Yer Depremleri Hakkında Yeni Araştırmalar.” [New findings about earthquakes] Arkitekt, no. 9–10, 1943, p. 211 (http://dergi.mo.org.tr). Anhegger, Robert. Report about my journey to Yozgat, 1945. Ernst Reuter Papers (Landesarchiv Berlin, 1945), Rep. 200–21, Acc. 1180, Nr. 48.

Anonymous. “‘Cili’ kira evi. Taksim. Mimar Zeki Sayâr.” Arkitekt, no. 1, 1936, pp. 1–8.

Baum, David. “Wilhelm Schütte als Vermittler und Architekt im Nachkriegs-Wien (1947– 1968).” Wilhelm Schütte. Architekt. Frankfurt, Moskau, Istanbul, Wien, edited by ÖGFA – Österreichische Gesellschaft für Architektur, Ute Waditschatka, Park Books, 2019, pp. 64–91.

Baum, David. “Wilhelm Schütte – im Schatten Lihotzkys?.” Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Architektur. Politik. Geschlecht. Neue Perspektiven auf Leben und Werk (Edition Angewandte), edited by Marcel Bois and Bernadette Reinhold, Birkhäuser, 2019, pp. 208–223.

Demir, Ataman. Arşivdeki belgeler ışığında Güzel Sanatlar Akademisi’nde Yabancı hocalar. Philipp Ginther’den (1929) – (1958) Kurt Erdmann’a kadar. Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi, 2008.

Diez, Ernst. Letter to Beryl Diez. Ernst Diez Papers (Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel, 3 December 1943).

Dogramaci, Burcu. Kulturtransfer und nationale Identität. Deutschsprachige Architekten, Stadtplaner und Bildhauer in der Türkei nach 1927. Gebr. Mann, 2008.

Dogramaci, Burcu. Fotografieren und Forschen. Wissenschaftliche Expeditionen mit der Kamera im türkischen Exil nach 1933. Jonas, 2013.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Architekt, Lehrer, Autor: Wilhelm Schütte in der Türkei (1938–1946).” Wilhelm Schütte. Architekt. Frankfurt, Moskau, Istanbul, Wien, edited by ÖGFA – Österreichische Gesellschaft für Architektur, Ute Waditschatka, Park Books, 2019, pp. 48–63.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Intermezzo in Istanbul. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzkys Projekte im türkischen Exil.” Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Architektur. Politik. Geschlecht. Neue Perspektiven auf Leben und Werk (Edition Angewandte), edited by Marcel Bois and Bernadette Reinhold, Birkhäuser, 2019, pp. 126–139.

Flierl, Thomas. “Margarete Schütte-Lihotzkys sowjetische Jahre (1930–1937).” Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Architektur. Politik. Geschlecht. Neue Perspektiven auf Leben und Werk (Edition Angewandte), edited by Marcel Bois and Bernadette Reinhold, Birkhäuser, 2019, pp. 100–125.

Flierl, Thomas. “Wilhelm Schütte als Schulbauexperte in der Sowjetunion (1930–1937).” Wilhelm Schütte. Architekt. Frankfurt, Moskau, Istanbul, Wien, edited by ÖGFA – Österreichische Gesellschaft für Architektur, Ute Waditschatka, Park Books, 2019, pp. 24–47.

Flierl, Thomas. “Mit einem Karton voller Briefe auf Zeitreise.” Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte. “Mach den Weg um Prinkipo, meine Gedanken werden Dich dabei begleiten!” Der Gefängnis-Briefwechsel 1941–1945, edited by Thomas Flierl, Lukas Verlag, 2021, pp. 409–576.

.Nicolai, Bernd. Moderne und Exil. Deutschsprachige Architekten in der Türkei 1925–1955. Verlag für Bauwesen, 1998.

Noever, Peter, editor. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Soziale Architektur. Zeitzeugin eines Jahrhunderts (2nd ed.). Böhlau, 1996.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Zelzele sahalarının yeniden imari hakkında düşünceler.” Arkitekt, no. 3–4, 1940a, pp. 75–87.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Büyük şehirlerin inkişaf meseleleri.” Arkitekt, no. 9–10, 1940b, pp. 211–213.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Th. Fischer ve Proporsiyonlar.” Arkitekt, no. 9–10, 1940c, pp. 224–225.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Adolf Loos.” Arkitekt, no. 1–2, 1941a, pp. 41–45.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Sefalet mahalleleri.” Arkitekt, no. 3–4, 1941b, pp. 78–87.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Karl Friedrich Schinkel 1781–1841. Bugün bizlere ne ifade eder?.” Arkitekt, no. 5–6, 1943a, pp. 131–135.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Yer Depremleri Hakkında Yeni Araştırmalar.” Arkitekt, no. 9–10, 1943b, pp. 211–215.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Mimar Yetiştirimi.” Arkitekt, no. 11–12, 1943c, pp. 258–260.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Bugünkü kültür ve ikametgâh.” Arkitekt, no. 1–2, 1944, pp. 28–31 and no. 3–4, 1944, pp. 66–70.

Schütte, Wilhelm. “Entwicklung erdbebenfester Bauweisen.” Seismische Arbeiten (Veröffentlichungen des Zentralinstituts für Erdbebenforschung in Jena, no. 51), Akademie Verlag, 1949, pp. 99–129.

Schütte, Wilhem. “Erziehung zum Architekten.” Der Aufbau. Monatsschrift für den Wiederaufbau, vol. 8, no. 10, 1953, pp. 507–509.

Schütte-Lihotzky, Margarete. Yeni köy okulları bina tipleri üzerinde bir deneme. Schütte-Lihotzky Papers (unpublished manuscript, Ankara, 1939, University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive).

Schütte-Lihotzky, Margarete. “Wie mein Kopf gerettet wurde.” Die Zwanziger Jahre des Deutschen Werkbunds (Werkbund Archiv, 10), edited by Deutscher Werkbund and Werkbund-Archiv, Anabas, 1982, pp. 313–316.

Schütte-Lihotzky, Margarete. Erinnerungen aus dem Widerstand 1938–1945, edited by Chup Friemert, Konkret Literatur Verlag, 1985.

Schütte-Lihotzky, Margarete, and Wilhelm Schütte. “Mach den Weg um Prinkipo, meine Gedanken werden Dich dabei begleiten!” Der Gefängnis-Briefwechsel 1941–1945, edited by Thomas Flierl, Lukas Verlag, 2021.

Word Count: 612

ÖGFA – Österreichische Gesellschaft für Architektur, Vienna, Archive Wilhelm Schütte.

University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive, Estate Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky.

Word Count: 23

My deepest thanks go to Daniel Baum and Thomas Flierl, who helped with information, and to the ÖGFA – Österreichische Gesellschaft für Architektur, Vienna, to the

University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive and to Luzie Lahtinen-Stransky, who gave me permission for reproduction. The digital copies of Arkitekt magazine published by Mimarlar Odası were of great value for this entry.Word Count: 60

- Istanbul

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte Apartment." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5140-10969688, last modified: 18-09-2021.

-

Rudolf BellingSculptorIstanbul

As a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts and Technical University in Istanbul from 1937 until 1966, Rudolf Belling taught his students the technicalities of form, material and proportion.

Word Count: 28

ArkitektMagazineIstanbulThe architecture magazine Arkitekt was an important platform for emigrated architects and urban planners such as Bruno Taut, Martin Wagner, Wilhelm Schütte, Ernst Reuter and Gustav Oelsner.

Word Count: 28

Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze kadarBookIstanbulThe Viennese Ernst Diez lived in Turkey from 1943 to 1950. His textbook Türk Sanatı (1946) stirred a debate on Turkish art and its relations to Byzantine and Armenian art.

Word Count: 28

Festive architecture for the 15th anniversary of the Turkish RepublicTemporary street architectureIstanbulOne of the first commissions of the architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte, who emigrated to Istanbul in 1938, was a street architecture for the anniversary of the Turkish Republic.

Word Count: 31

Bruno Taut HouseResidenceIstanbulArchitect Bruno Taut’s house in Ortaköy stands on a hillside with a panoramic view of the Bosporus, located at the point where Asia and Europe are closest to one another.

Word Count: 32

Mimarî BilgisiBookIstanbulThe architect Bruno Taut published his textbook Mimarî Bilgisi in 1938, only two years after his emigration to Istanbul, where he was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Word Count: 29

Jules KanzlerPainterPhotographerIstanbulKanzler spent part of his life in the Russian Empire as a painter and the other in Turkey as a photographer who “documented” the early years of the Turkish Republic.

Word Count: 30