Archive

Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze kadar

- Book

- Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze kadar

Word Count: 12

- (Turkish Art. From the Beginning until Today)

- 1946

Üniversite Matbaası Komandit Şti., Tünelbaşı (now Tünel Meydanı), Beyoğlu, Istanbul (publishing house).

- Turkish

- Istanbul (TR)

The Viennese Ernst Diez lived in Turkey from 1943 to 1950. His textbook Türk Sanatı (1946) stirred a debate on Turkish art and its relations to Byzantine and Armenian art.

Word Count: 28

Ernst Diez. Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze Kadar. Univ. Matbaası, 1946, p. 49.

Ernst Diez. Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze Kadar. Univ. Matbaası, 1946 (University of Hamburg, Library of the Asien-Afrika-Institut).

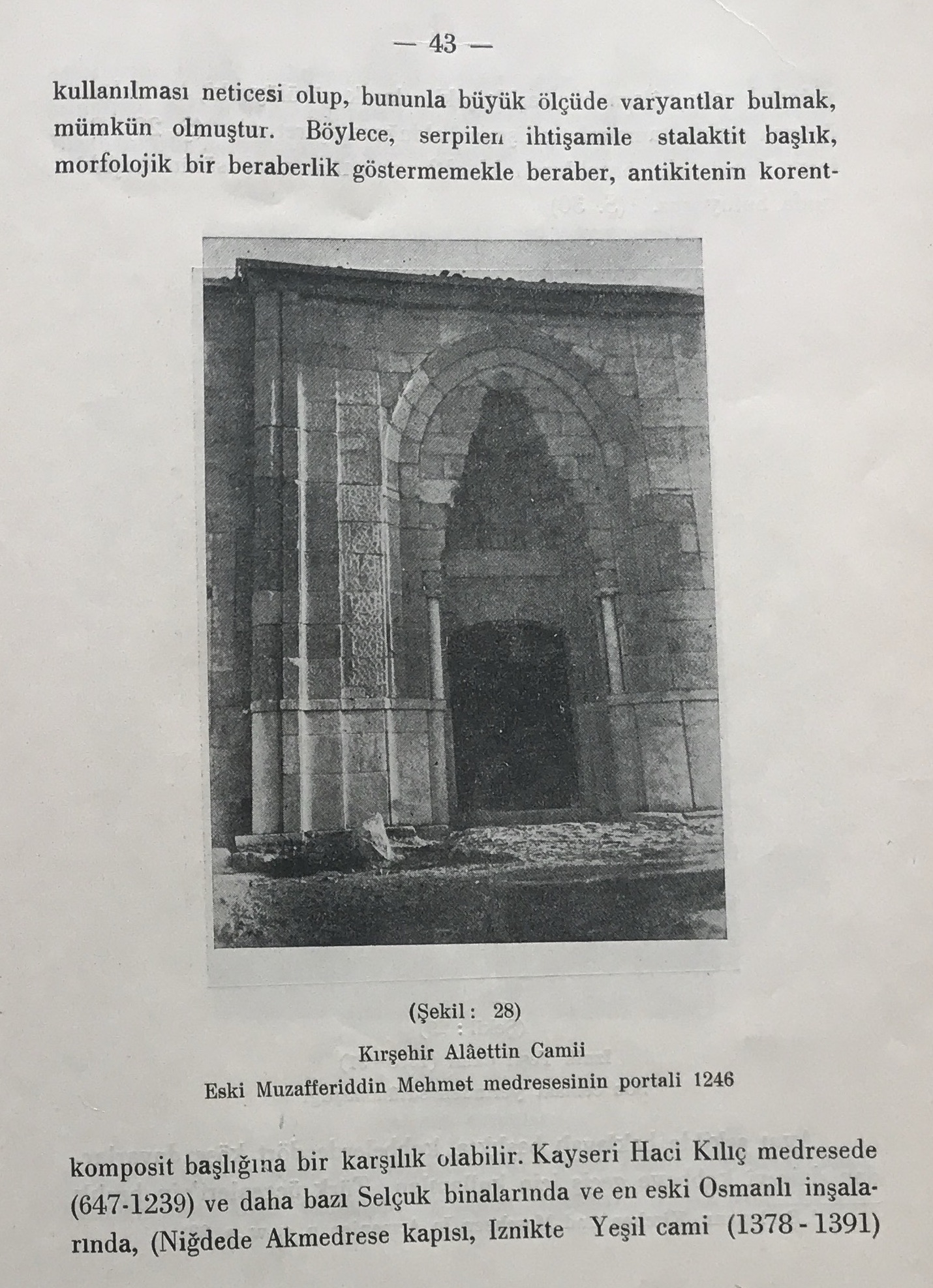

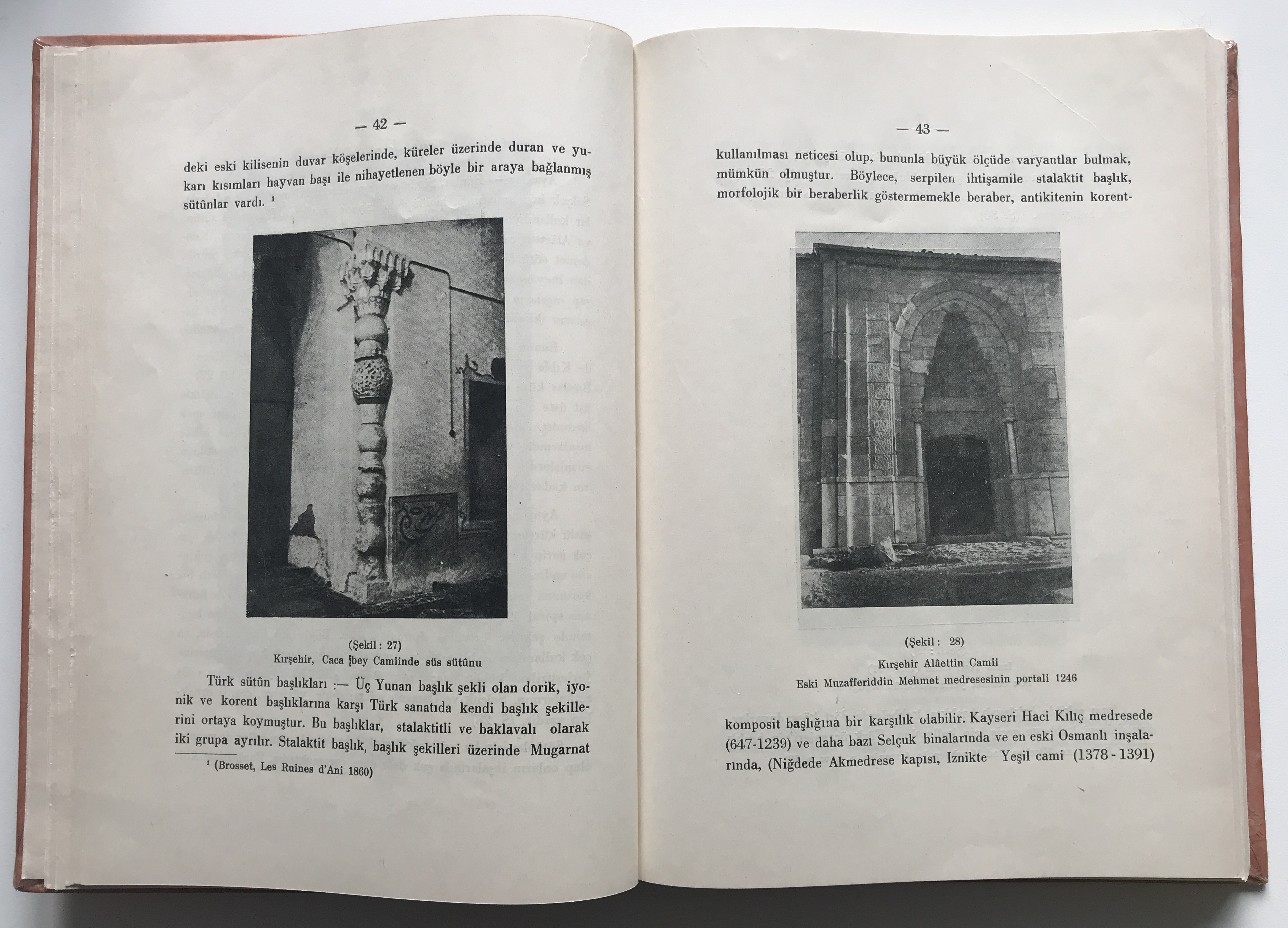

Ernst Diez. Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze Kadar. Univ. Matbaası, 1946, pp. 42–43. Diez illustrated his book with photographs from his internment in Kırşehir (University of Hamburg, Library of the Asien-Afrika-Institut).

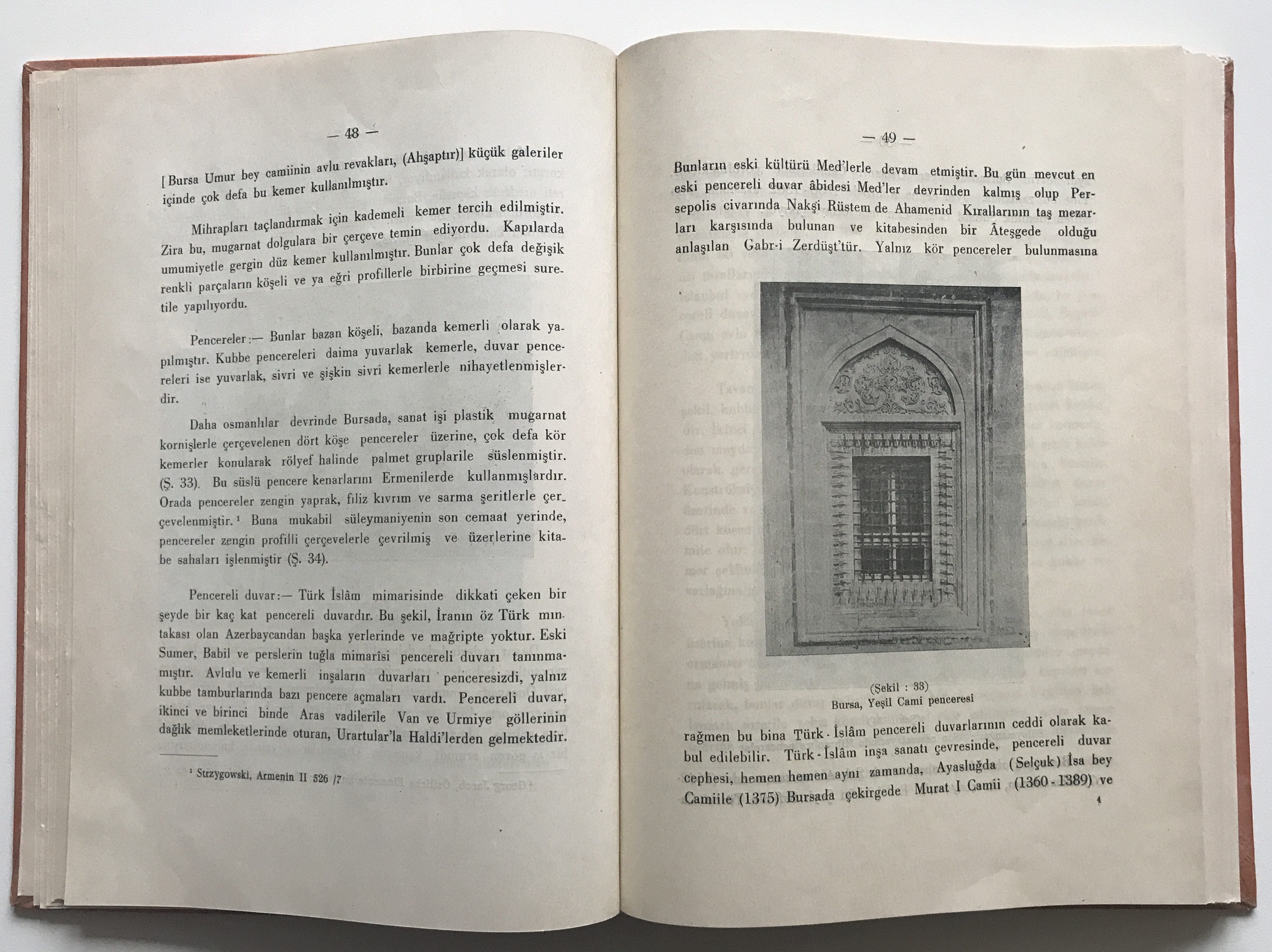

Ernst Diez. Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze Kadar. Univ. Matbaası, 1946, pp. 48–49. Diez mentions Yeşil Cami (Green mosque) in Bursa and emphasises the impact of Armenian architecture (University of Hamburg, Library of the Asien-Afrika-Institut).

Ernst Diez. Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze Kadar. Univ. Matbaası, 1946, pp. 84–85. Double page with Diez’s photograph of Melik Gazi Türbe in Kırşehir (University of Hamburg, Library of the Asien-Afrika-Institut).

Ernst Diez. Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze Kadar, Istanbul: Univ. Matbaası, 1946, pp. 172–173. Double page with photographs of Şehzade and Yeni Valide mosques in Istanbul. (University of Hamburg, Library of the Asien-Afrika-Institut).

Ernst Diez. Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze Kadar. Univ. Matbaası, 1946, pp. 176–177. Comparison between Ayasofya (Hagia Sophia) and Süleymaniye mosque. (University of Hamburg, Library of the Asien-Afrika-Institut).

Ernst Diez, Turkey, around 1946 (Aslanapa 1993).

Ernst Diez and Oktay Aslanapa (right beside him) on a student excursion to the Prince's Islands in Istanbul, 23 April 1950 (Estate of Oktay Aslanapa, Istanbul). Aslanapa, Oktay, editor. Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte Asiens. In Memoriam Ernst Diez. Istanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakultesi Yayınları, 1963.

Aslanapa, Oktay. Türkiye’de Avusturyalı Sanat Tarihçileri ve Sanatkârlar. Eren Yayıncılık, 1993.

Çetintaş, Sedat. “Türk Sanatı’ kitabının çeşitli hataları.” Mimarlık, no. 2, 1948, pp. 20–21.

Diez, Ernst. Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze Kadar. Universite Matbaası, 1946.

Diez, Ernst. “Endosmosen.” Felsefe Arkivi, vol. 2, no. 1, 1947, pp. 221–238.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Kunstgeschichte in Istanbul. Die Begründung der Disziplin durch den Wiener Kunsthistoriker Ernst Diez.” Kunstgeschichte im „Dritten Reich“. Theorien, Methoden, Praktiken (Schriften zur modernen Kunsthistoriographie, 1), edited by Ruth Heftrig et al., Akademie, 2008, pp. 114–133.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Josef Strzygowski, Ernst Diez et la construction d’une histoire nationale de l’art turc.” Austriaca. Cahiers universitaires d’information sur l’Autriche, no. 74: Vienne, porta Orientis, edited by Dieter Hornig et al., Mont-Saint-Aignan Cedex, 2013, pp. 158–172.

Ellinger, Ekkehard. Deutsche Orientalistik zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933–1945. Deux-Mondes-Verlag, 2006.

Eyice, Semavi. “I.Ü. Edebiyat Fakültesi sanat tarihi kürsüsü’nün kurucusu Prof. Dr. Ernst Diez (1878–1961).” Sanat Tarihi Yıllığı, XIV: 50. Kuruluş Yıldönümü Özel Sayısı, 1997, pp. 3–15.

Mülayim, Selçuk. “Sanat Tarihinin Attilası Josef Strzygowski.” Sanat Tarihi Araştirmaları Dergisi, no. 8, 1989, pp. 65–69.

Nureddin, Vâla [Vâ-Nû]. “Gelelim yerli profesörlere.” Akşam (Istanbul), 8 April 1949, n.p.

Öz, Tahsin. “Türk Sanatı kitabı dolayısıyle.” Vatan (Istanbul), 22 January 1947, n.p.

Word Count: 233

Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel, Ernst Diez Papers.

Word Count: 7

This entry is dedicated to the memory of Oktay Aslanalpa (1914–2013), who shared his knowledge of Ernst Diez with me and provided me with materials from his collection. My thanks go to Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel, for giving me access to the Ernst Diez Papers.

Word Count: 44

- Istanbul

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Türk Sanatı. Başlangıcından Günümüze kadar." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5140-10990269, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

Traugott FuchsPhilologistRomanistPoetPainterIstanbul

Traugott Fuchs was a multi-talented philologist, painter and poet who lived in Istanbul from 1934 until the end of his life in 1997.

Word Count: 21

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte ApartmentResidenceIstanbulThe exiled architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte lived from 1938 in an apartment in Kabataş, on the European side of Istanbul. The flat has been preserved in numerous photographs, allowing the interior design to be reconstructed. The view of the Bosporus from the balcony was spectacular.

Word Count: 48

Vladimir KadulinPainterCaricaturistIstanbulWhen it comes to Russian émigré caricaturists in Istanbul, Vladimir Kadulin who worked under the pseudonym Nayadin for the almanac Zarnitsy is the first to come to mind.

Word Count: 28