Archive

Russkiy v Konstantinopole/Le Russe à Constantinople

- Guide-book

- Russkiy v Konstantinopole/Le Russe à Constantinople

Word Count: 6

- Русский в Константинополе

- 1921

- 1921

Hardcover, dark-red. 44 pages.

Tipografiya “PRESSA”, Asmalı Mescit 35 (now presumably 23), Pera/Beyoğlu, Istanbul.

- Russian

- Istanbul (TR)

The guide-book was created for Russian-speaking refugees who had to leave their country and settle in Constantinople.

Word Count: 17

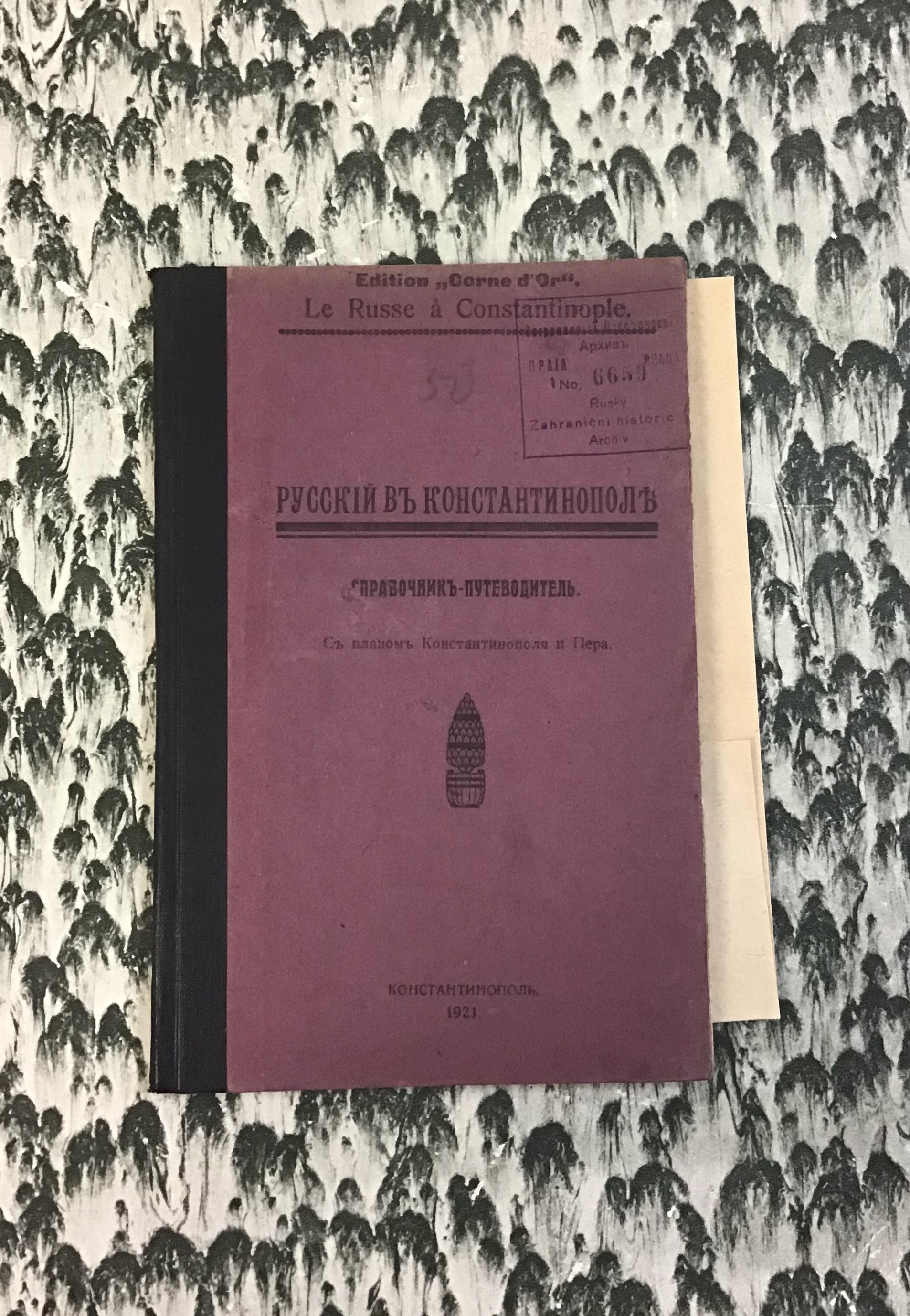

Russkiy v Konstantinopole / Le Russe à Constantinople, 1921, cover (Slavonic Library/Slovanská knihovna, Prague).

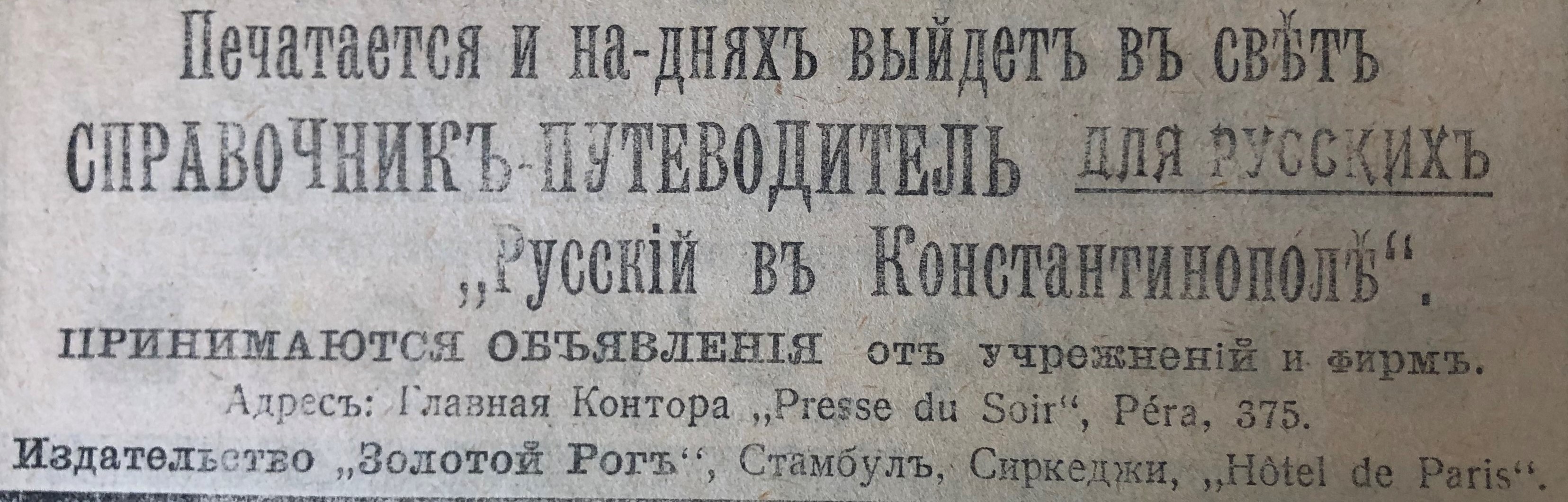

Announcement concerning the publication of the guide-book in the Russian newspaper Presse du Soir, 1921, n.p. (Slavonic Library/Slovanská knihovna, Prague).

Russkiy v Konstantinopole / Le Russe à Constantinople, 1921, cover (Slavonic Library/Slovanská knihovna, Prague).

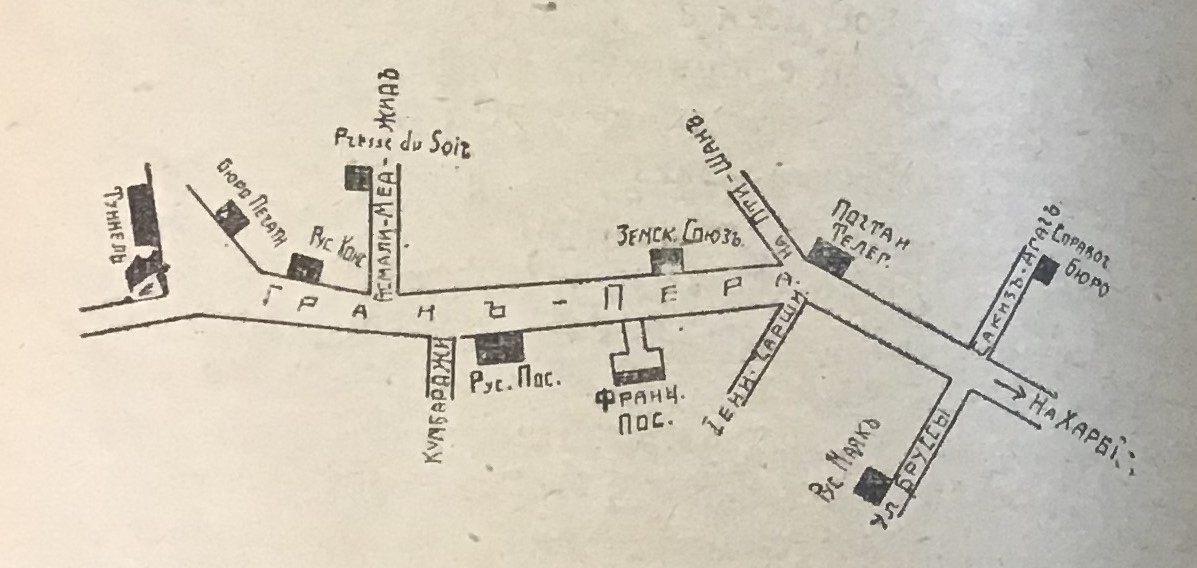

Layout of the Grand Rue de Péra (Istiklal Street) from the guide-book, 1921 (Slavonic Library/Slovanská knihovna, Prague).

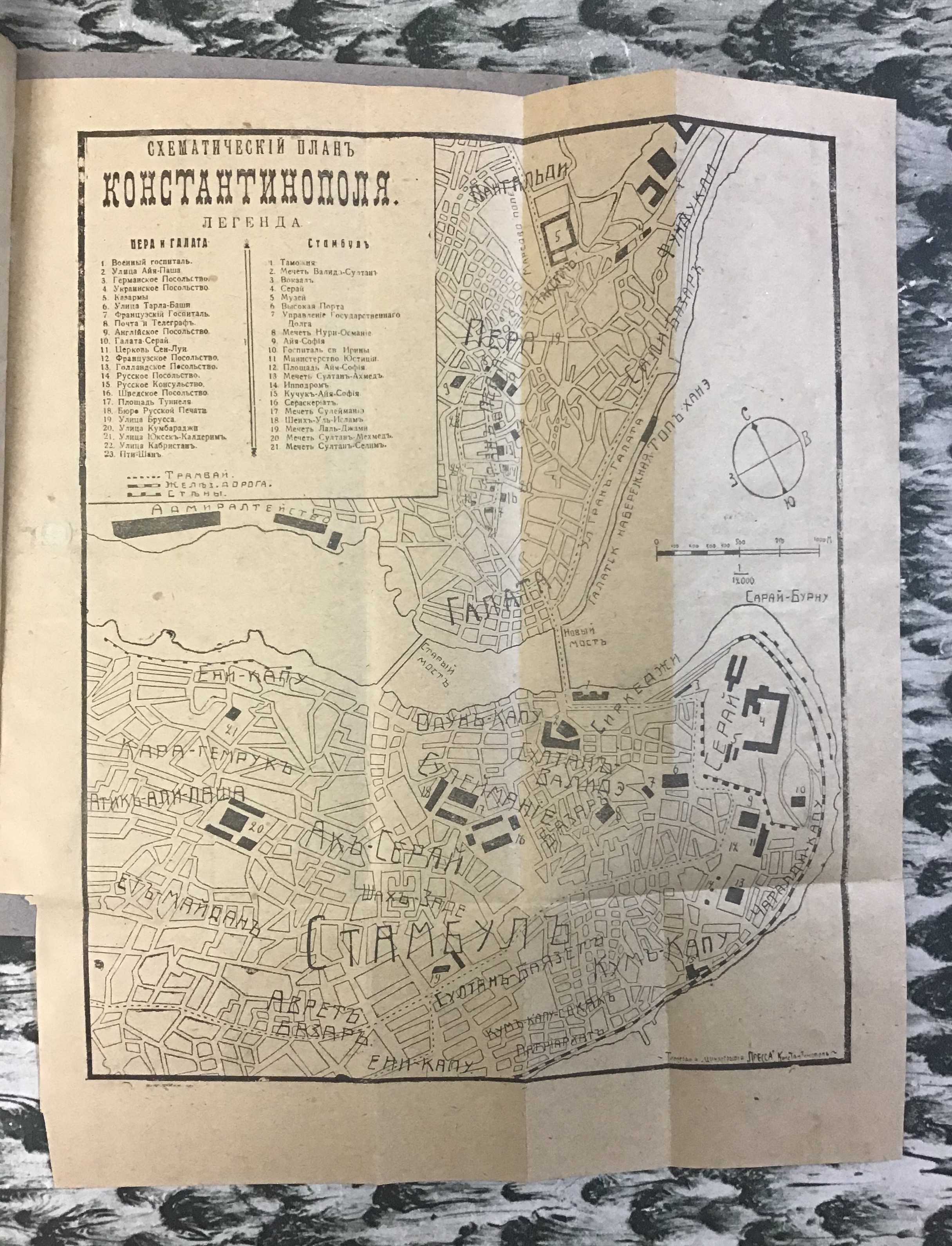

Schematic plan of Constantinople for ‘Russian’ refugees in the guide-book Russkiy v Konstantinopole/Le Russe à Constantinople, 1921 (Slavonic Library/Slovanská knihovna, Prague).

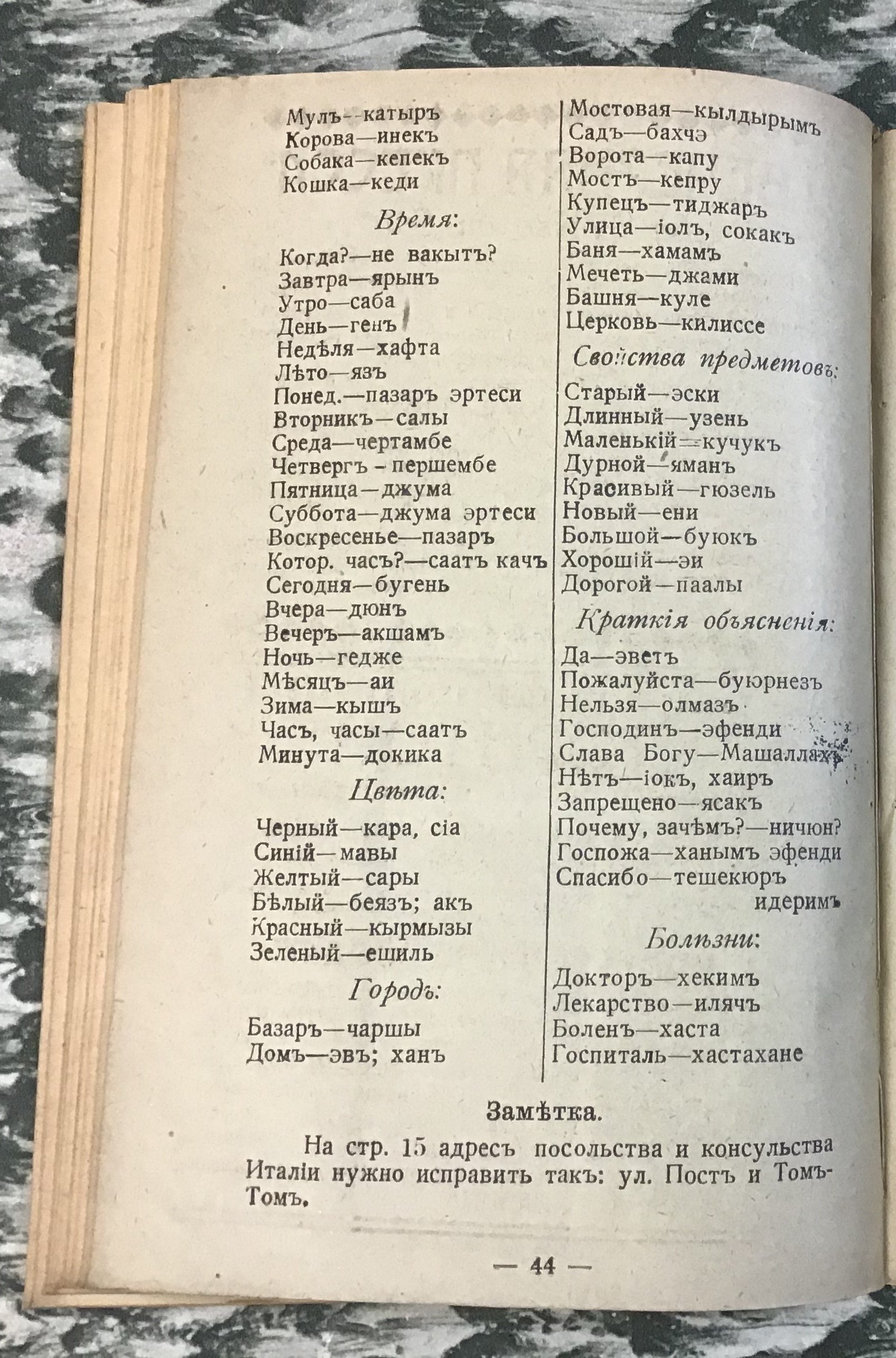

Most common words in Turkish for ‘Russian’ refugees from the guide-book, 1921 (Slavonic Library/Slovanská knihovna, Prague). Anonymous. Russkiy v Konstantinopole. Le Russe à Constantinople. Konstantinopl’: Tipografiya “Pressa”, 1921.

Word Count: 10

Slavonic Library (Slovanská knihovna) in Prague.

Word Count: 6

I would like to thank the representatives of the Slavonic Library (Slovanská knihovna) in Prague for helping me tremendously during my work at the library.

Word Count: 25

- Pera Palace Hotel

- Istanbul

- Ekaterina Aygün. "Russkiy v Konstantinopole/Le Russe à Constantinople." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5140-11876457, last modified: 14-09-2021.

-

Leon TrotskyPoliticianIstanbul

Banished by Stalin, the revolutionary politician Leon Trotsky and his entourage arrived in Istanbul in 1929. He settled on Büyükada, one of the Princes’ Islands in the Sea of Marmara.

Word Count: 31

Alexis GritchenkoPainterArt HistorianIstanbulDuring the two years of his life that he spent in Istanbul, Alexis Gritchenko produced more paintings dedicated to the city than many artists produce in an entire lifetime.

Word Count: 29

Dimitri IsmailovitchPainterArt HistorianIstanbulIn Istanbul, Ismailovitch became one of the leaders of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, organised three solo exhibitions, and made contribution to the study of Byzantine art.

Word Count: 29

Vladimir KadulinPainterCaricaturistIstanbulWhen it comes to Russian émigré caricaturists in Istanbul, Vladimir Kadulin who worked under the pseudonym Nayadin for the almanac Zarnitsy is the first to come to mind.

Word Count: 28

Lydia NikanorovaPainterIstanbulIn Istanbul, Nikanorova worked at copying the mosaics and frescoes of the Kariye Mosque, and met her future husband, Georges Artemoff, also an émigré artist from the former Russian Empire.

Word Count: 30

First Russian émigré artists in Istanbul exhibitionExhibitionIstanbulThe first Russian-speaking émigré artists in Istanbul exhibition was a one-day event but its success led to the formation of the Union and paved the way for other exhibitions.

Word Count: 29

Union of Russian Painters in ConstantinopleAssociationIstanbulThe Union existed for less than two years but in that short space of time a tremendous amount of work was done by its members, refugees from the Russian Empire.

Word Count: 30

Pera Palace HotelHotelIstanbulThe Pera Palace was the gem of Pera district where people gathered to wine and dine and be entertained, as well as to discuss the issues of the day.

Word Count: 29

RejansCafé / RestaurantIstanbulRejans (now 1924 Istanbul) restaurant, at the end of the Olivya Passageway is one of Beyoğlu’s landmarks. A relic of 1920s “Russian Istanbul”, where the original atmosphere has been preserved.

Word Count: 31