Archive

Bruno Taut House

- Residence

- Bruno Taut House

Word Count: 3

- Bruno Taut evi

- Bruno Taut

- 1938

Emin Vafi Korusu, Ortaköy, Istanbul (residence).

- İstanbul (TR)

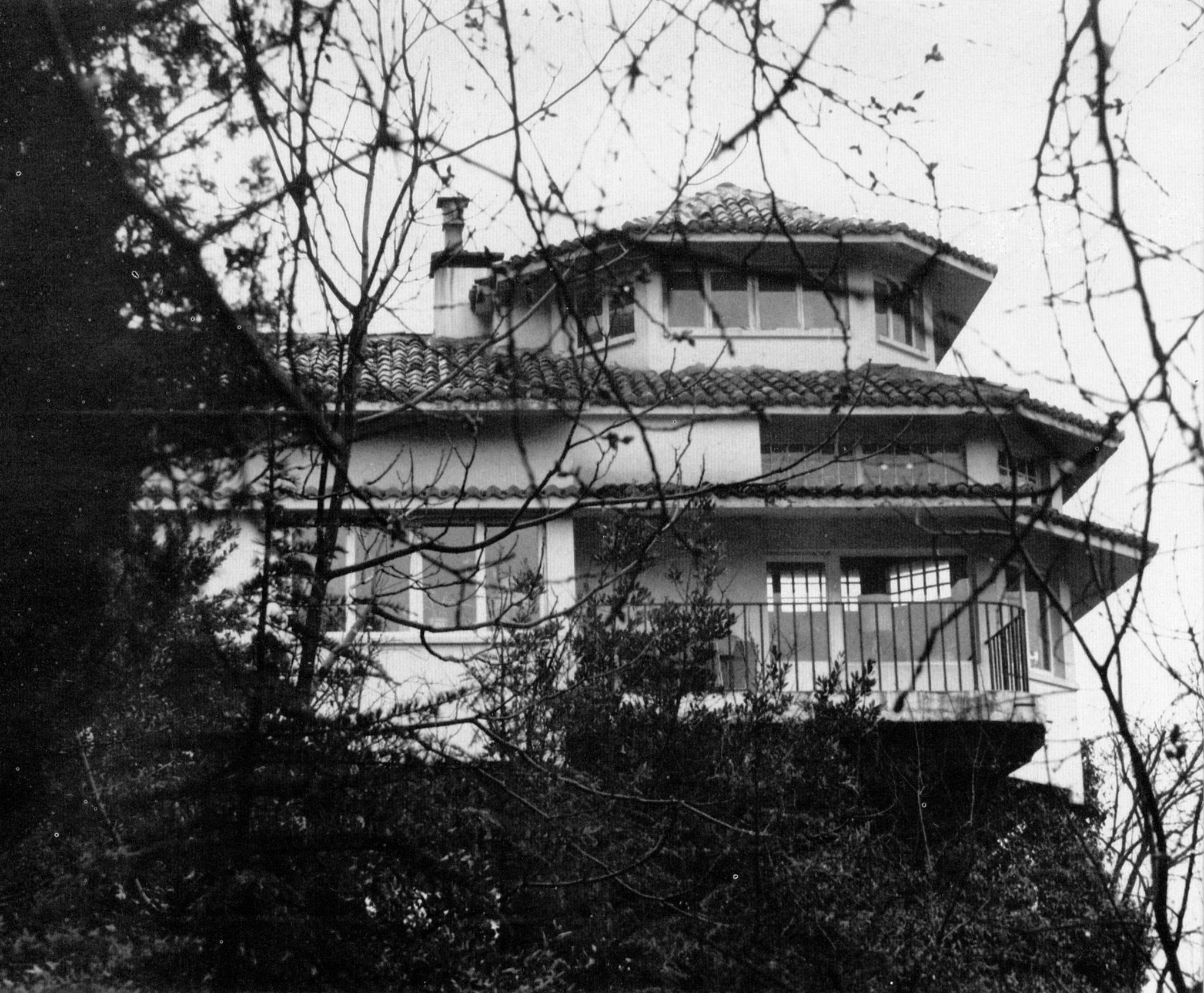

Architect Bruno Taut’s house in Ortaköy stands on a hillside with a panoramic view of the Bosporus, located at the point where Asia and Europe are closest to one another.

Word Count: 32

Yapı, No. 13, 1975, cover with Bruno Taut House at the Bosporus, photo: Bülent Özer (Private Archive).

Bruno Taut House, Istanbul Ortaköy, Emin Vafi Korusu, 1937/38 (Junghanns 1983, ill. 331).

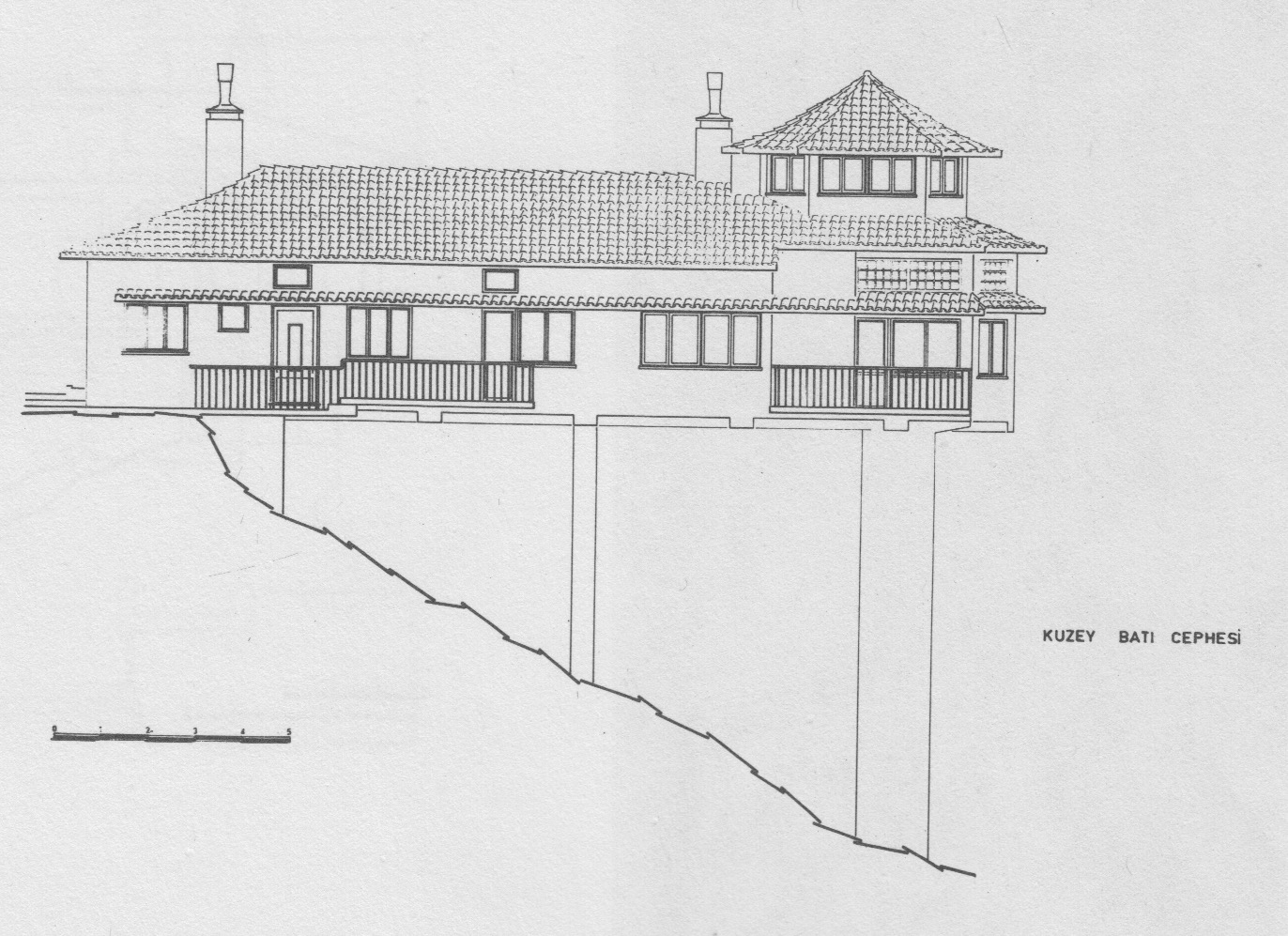

Bruno Taut House, Istanbul Ortaköy, 1937/38, view from northwest, drawing by Tulay Gündüz und Mesut Işcan, 1967 (Yapı, No. 13, 1975).

Erica Wittich-Taut, Bruno Taut (l.) and the architect Şinasi Lugal at Taut’s exhibition, opened up at the Academy of Fine Arts, Istanbul, June 1938 (Archive Manfred Speidel). Akcan, Esra. Architecture in Translation. Germany, Turkey, & the Modern House. Duke University Press, 2012.

Aslanoğlu, Inci. “Bruno Tauts Wirken als Lehrer und Architekt in der Türkei.” Bruno Taut: 1880–1938, exh. cat. Akademie der Künste, Berlin 1980, pp. 143–150.

Dogramaci, Burcu. Kulturtransfer und nationale Identität. Deutschsprachige Architekten, Stadtplaner und Bildhauer in der Türkei nach 1927. Gebr. Mann, 2008.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Home, Heimat, foreign land. Bruno Taut’s villa on the Bosporus and the architect’s house in emigration.” A Home of One’s Own. Emigrierte Architekten und ihre Häuser. 1920–1960 / Émigré Architects and their Houses. 1920–1960, edited by Burcu Dogramaci and Andreas Schätzke, Edition Axel Menges, 2019, pp. 93–107.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Arrival City Istanbul: Flight, Modernity and Metropolis at the Bosporus. With an Excursus on the Island Exile of Leon Trotsky.” Arrival Cities. Migrating Artists and New Metropolitan Topographies in the 20th Century, edited by Burcu Dogramaci et al., Leuven University Press, 2020, pp. 205–225.

Jaeger, Roland. “Bau und Buch: Ein ‘Wohnhaus’ von Bruno Taut.” Bruno Taut: Ein Wohnhaus (1927). Gebr. Mann, 1995, pp. 119–147.

Junghanns, Kurt. Bruno Taut, 1880–1938. Henschel, 1983.

Nerdinger, Winfried, et al., editors. Bruno Taut 1880–1938. Architekt zwischen Tradition und Avantgarde. DVA, 2001.

Nicolai, Bernd. Moderne und Exil. Deutschsprachige Architekten in der Türkei 1925–1955. Verlag für Bauwesen, 1998.

Taut, Bruno. Das japanische Haus und sein Leben / Houses and People of Japan (1937). Gebr. Mann, 1997.

Zöller-Stock, Bettina. Bruno Taut. Die Innenraumentwürfe des Berliner Architekten. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1993.

Word Count: 228

Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Baukunstarchiv, Bruno Taut Papers.

Word Count: 9

My deepest thanks go to Manfred Speidel, who gave me permission to reproduce a photograph from his collection.

Word Count: 18

- Istanbul

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Bruno Taut House." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5140-8103249, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

ArkitektMagazineIstanbul

The architecture magazine Arkitekt was an important platform for emigrated architects and urban planners such as Bruno Taut, Martin Wagner, Wilhelm Schütte, Ernst Reuter and Gustav Oelsner.

Word Count: 28

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte ApartmentResidenceIstanbulThe exiled architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte lived from 1938 in an apartment in Kabataş, on the European side of Istanbul. The flat has been preserved in numerous photographs, allowing the interior design to be reconstructed. The view of the Bosporus from the balcony was spectacular.

Word Count: 48

Mimarî BilgisiBookIstanbulThe architect Bruno Taut published his textbook Mimarî Bilgisi in 1938, only two years after his emigration to Istanbul, where he was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Word Count: 29

Festive architecture for the 15th anniversary of the Turkish RepublicTemporary street architectureIstanbulOne of the first commissions of the architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte, who emigrated to Istanbul in 1938, was a street architecture for the anniversary of the Turkish Republic.

Word Count: 31