Archive

Türk Tarih Sergisi

- Türk Tarih Sergisi

Word Count: 4

(Turkish History Exhibition)

- Exhibition

- 1937

In 1937, the exiled urban planner Martin Wagner was commissioned to design an exhibition for a congress of the Association for the Study of Turkish History at Dolmabahçe Palace.

Word Count: 29

Martin Wagner, view of main exhibition room at the Türk Tarih Sergisi [Turkish History Exhibition], Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937 (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937). The different epochs of Turkish history from prehistoric times through the Ottomans to the Turkish Republic are described using a variety of objects and panels.

Martin Wagner during work on the Türk Tarih Sergisi [Turkish History Exhibition] at the Dolmabahçe Palace, 1937. Photographer unknown (Wagner, Bernard 1985, 46).

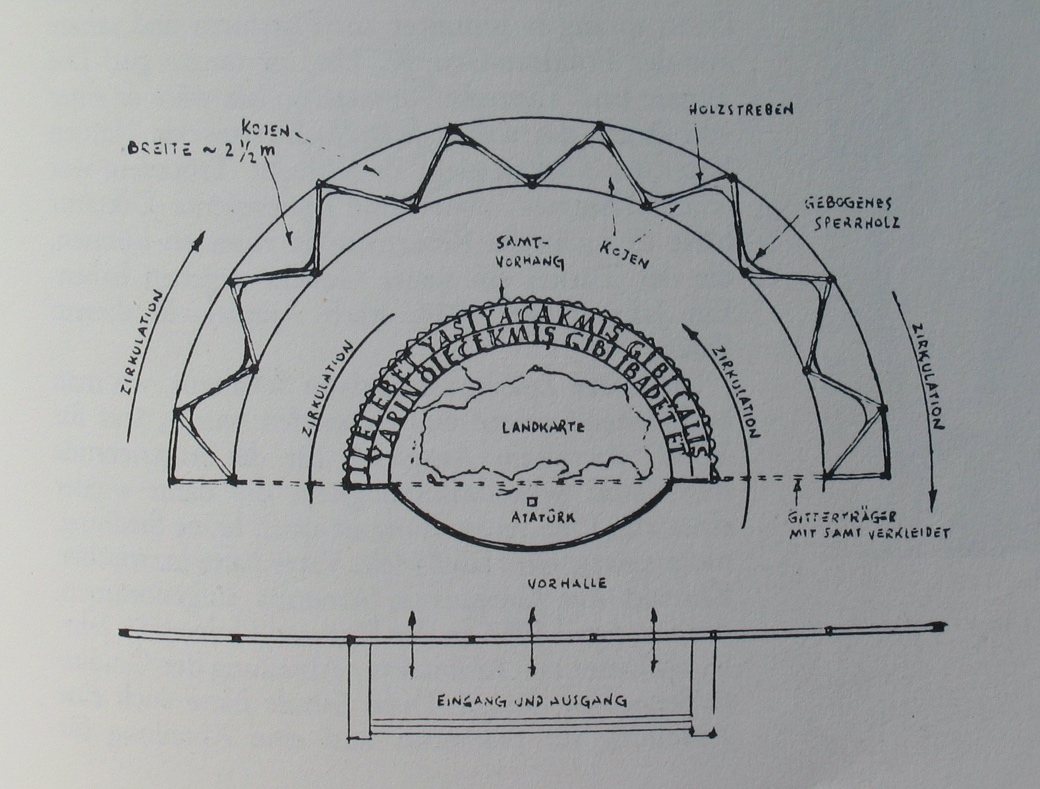

Martin Wagner, exhibition design, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937 (Wagner, Bernard 1985, 45). Here Wagner has made a sketch of the exhibition foyer, which he planned as an accessible semicircle.

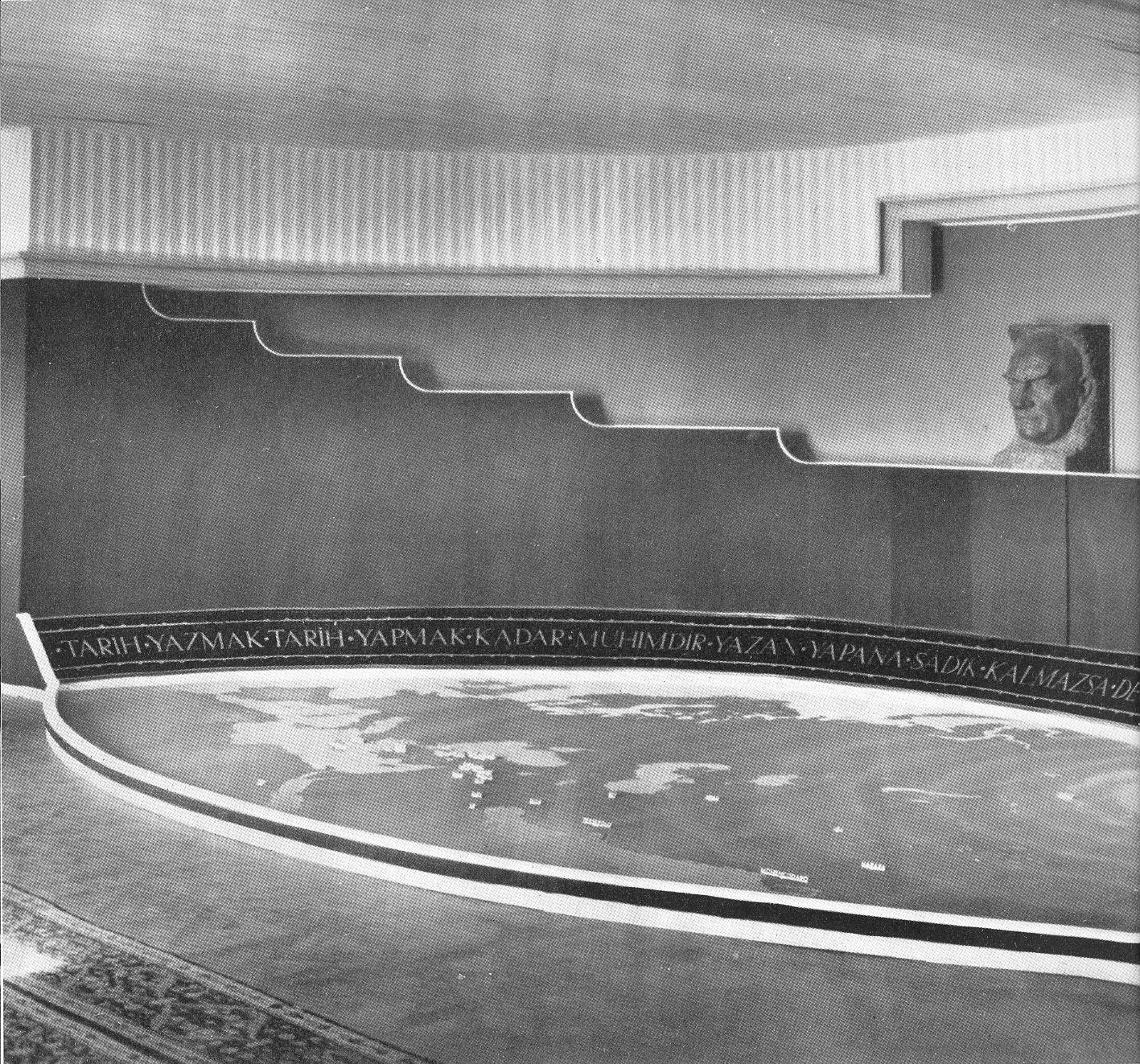

Martin Wagner, exhibition design, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Foyer (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937).

Martin Wagner, view of main exhibition room at the Türk Tarih Sergisi [Turkish History Exhibition], Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937 (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937). The different epochs of Turkish history from prehistoric times through the Ottomans to the Turkish Republic are described using a variety of objects and panels.

Martin Wagner, exhibition architecture, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Historical part: tomb, from Alaca Höyük (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937).

Martin Wagner, exhibition architecture, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Historical part: 16th century door (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937).

Martin Wagner, exhibition architecture, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Contemporary part (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937).

Martin Wagner, exhibition architecture, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Contemporary part: agriculture (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937). Agriculture is visualised by a large three-dimensional ear of grain placed in front of a farmer drawn in silhouette.

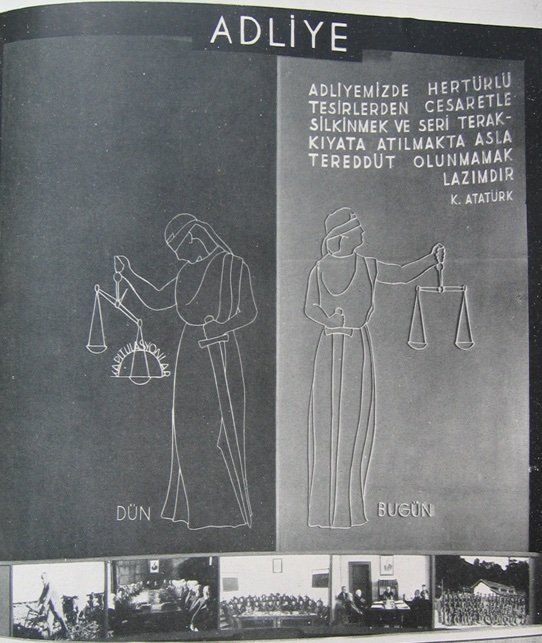

Martin Wagner, exhibition architecture, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Contemporary part: justice (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937). Wagner characterised the successes of Kemalist justice and the new legal system by personifying justice.

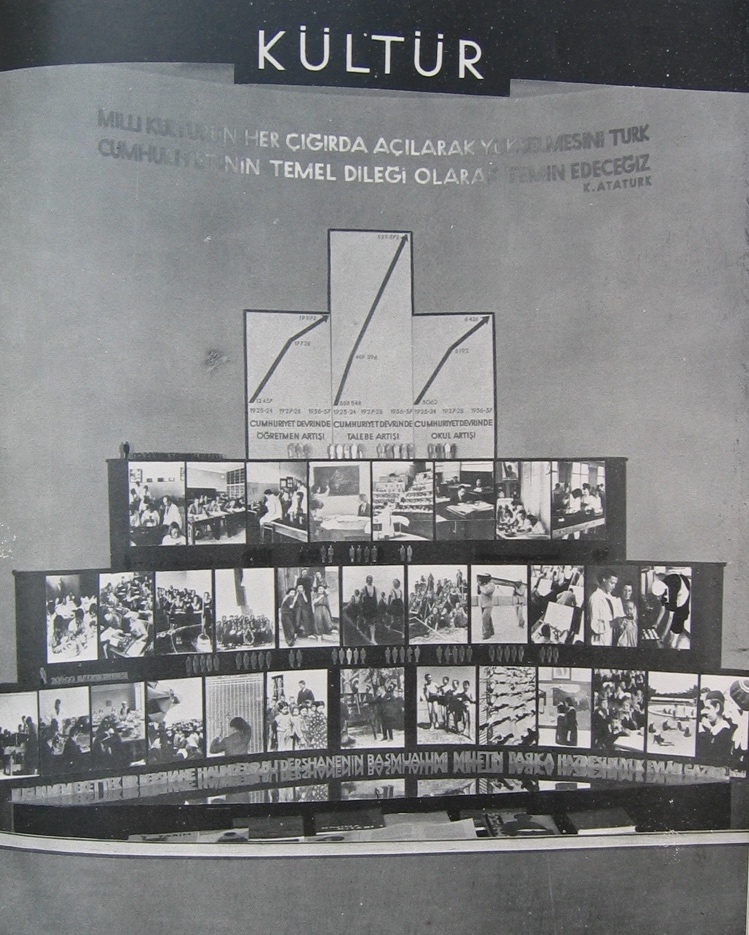

Martin Wagner, exhibition architecture, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Contemporary part: culture (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937).

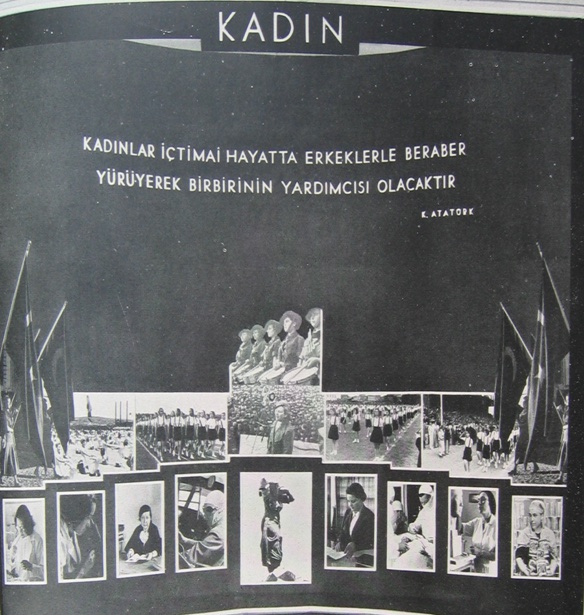

Martin Wagner, exhibition architecture, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Contemporary part: woman (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937).

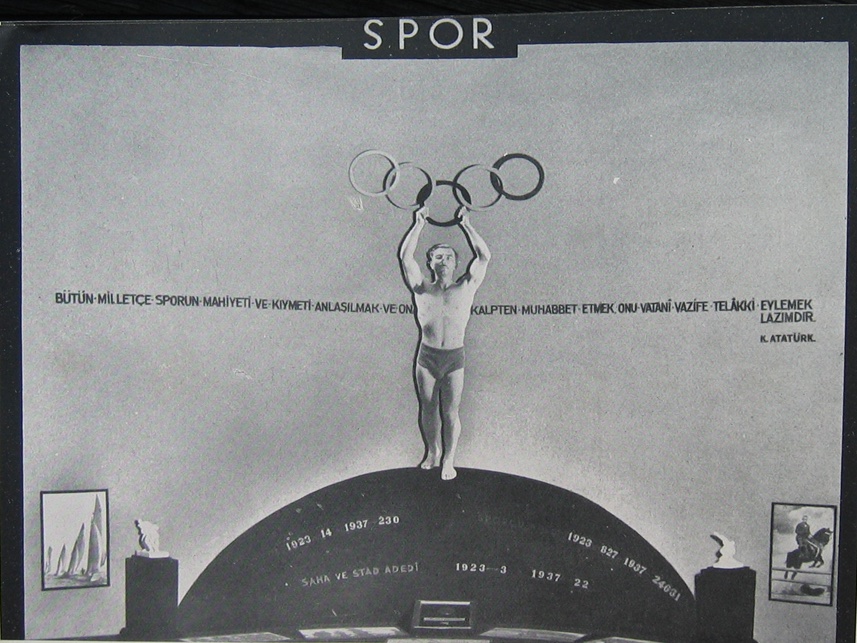

Martin Wagner, exhibition architecture, Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul, 1937. Contemporary part: sport (La Turquie Kemaliste 1937). The category “sport”, showing an athlete holding up the Olympic rings, paid homage to the new body awareness. Turkey participated in the Olympic Games for the first time in 1936. Bittel, Kurt. “Abteilung Istanbul.” Beiträge zur Geschichte des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 1929 bis 1979, Part 1. Phillip von Zabern, 1979, pp. 65–91.

Çoker, Amiral Fehri, editor. Türk Tarih Kurumu. Kuruluş Amacı ve Çalışmaları (Türk Tarih Kurumu yayınları, 48). Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1983.

Cumhuriyet. Resimli almanak 1937–38. Istanbul Cumhuriyet Matbaası, 1938.

Dogramaci, Burcu. Kulturtransfer und nationale Identität. Deutschsprachige Architekten, Stadtplaner und Bildhauer in der Türkei nach 1927. Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2008.

Egli, Ernst. “Zwischen Heimat und Fremde, einst und dereinst. Erinnerungen.” (unpublished manuscript, Zurich, 1969, Library of ETH Zurich, Ernst Egli Papers, Hs 787:1).

La Turquie Kemaliste, special issue, 1937.

Sungu, Ihsan. “L’Exposition d’Histoire.” La Turquie Kemaliste, special issue, 1937, p. 20.

Tekeli, Ilhan. “The social context of the development of architecture in Turkey.” Modern Turkish Architecture, edited by Renata Holod and Ahmet Evin, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984, pp. 9–33.

Wagner, Bernard. Martin Wagner 1885–1957. Leben und Werk. Eine biographische Erzählung. G.M.L. Wittenborn Söhne, 1985.

Word Count: 150

- Istanbul

- Burcu Dogramaci. "Türk Tarih Sergisi ." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5141-10990980, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

Rudolf BellingSculptorIstanbul

As a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts and Technical University in Istanbul from 1937 until 1966, Rudolf Belling taught his students the technicalities of form, material and proportion.

Word Count: 28

ArkitektMagazineIstanbulThe architecture magazine Arkitekt was an important platform for emigrated architects and urban planners such as Bruno Taut, Martin Wagner, Wilhelm Schütte, Ernst Reuter and Gustav Oelsner.

Word Count: 28