Archive

Konstantinopol’skiy Kommercheskiy Klub

- Konstantinopol’skiy Kommercheskiy Klub

Kommercheskiy Klub, ККК, Константинопольский Коммерческий Клуб, Constantinople Commercial Club. In January 1926 was renamed and began to be called KK or Konstantinopol’skiy Klub (Константинопольский Клуб).

- Club

KKK was probably the most popular Russian club in Beyoğlu district between 1924 and 1926. Not only Russian émigrés but also local residents could enjoy its constantly updated entertainment programme.

Word Count: 30

Istiklal Caddesi 322 (now presumably Istiklal Caddesi 130 – Elhamra Han), Beyoğlu, Istanbul.

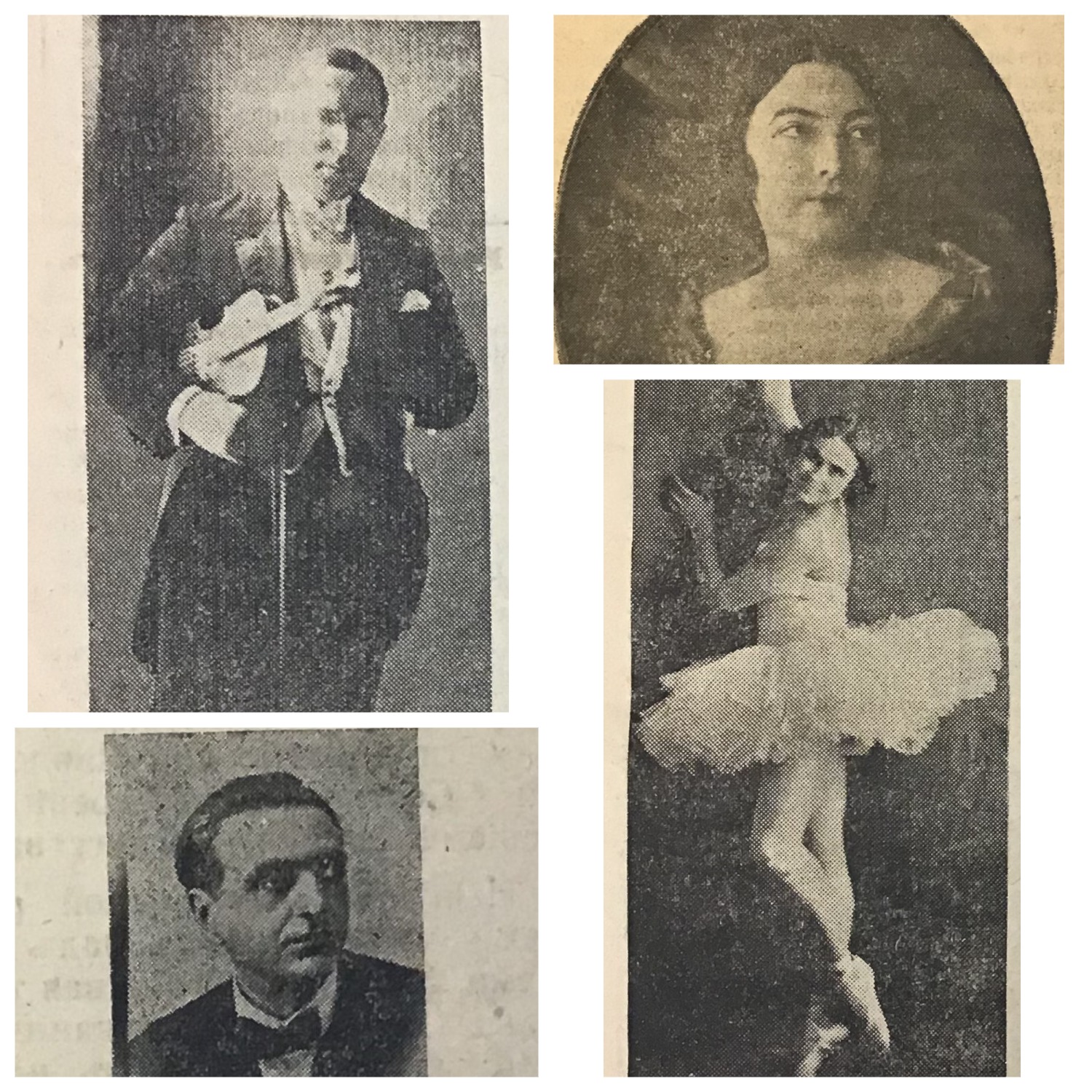

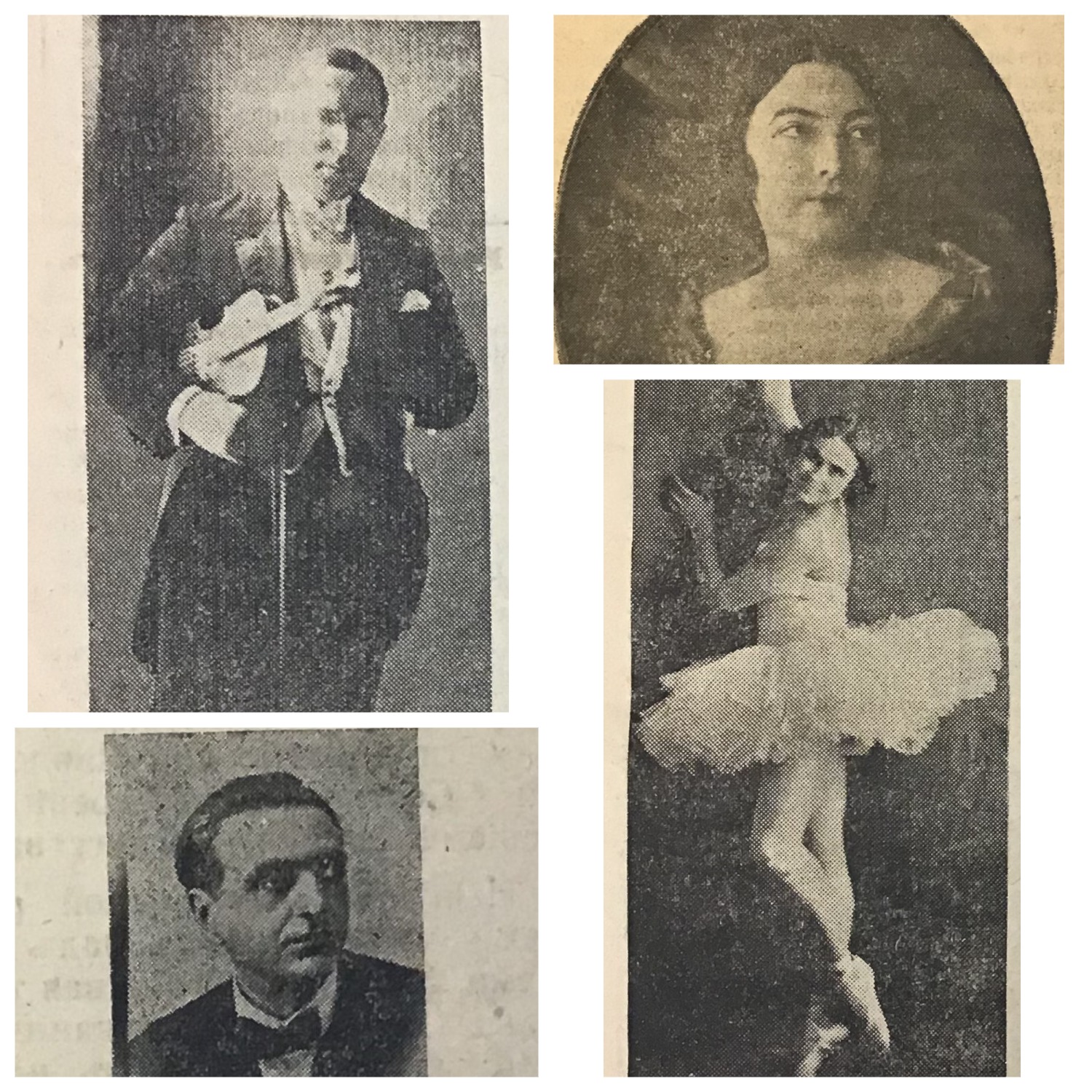

Some of the Russian artists who took an active part in the club’s events, clockwise from top left: violinist Pavel Alekseevich Zamoulenko, singer Maria de Monighetti, ballerina Yevgeniya Vorobyova, poet and musician Ivan Andreevich Korvatsky (Zarubezhnyi Klich almanacs of 1925).

The name of the club as listed in the Zarubezhnyi Klich almanac, April 1925.

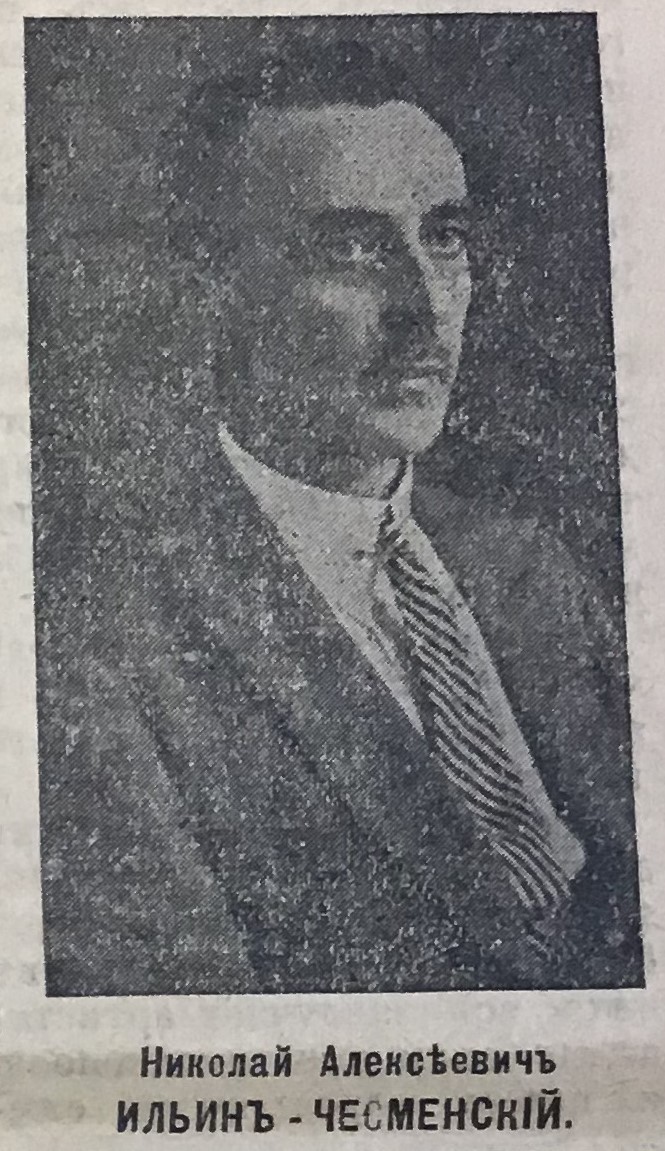

The first chairman of the club, Nikolai Alekseevich Ilyin-Chesmensky (Zarubezhnyi Klich almanac, April 1925, n.p.).

Some of the Russian artists who took an active part in the club’s events, clockwise from top left: violinist Pavel Alekseevich Zamoulenko, singer Maria de Monighetti, ballerina Yevgeniya Vorobyova, poet and musician Ivan Andreevich Korvatsky (Zarubezhnyi Klich almanacs of 1925).

Istiklal Caddesi 130 (Elhamra Han), Beyoğlu, Istanbul (Photo: Ekaterina Aygün, 2019). Anonymous. “Nash Klub.” Zarubezhnyi Klich, April 1925, pp. 5–13.

Vecherniaia Gazeta, almost all issues of 1924–1926.

Word Count: 13

Slavonic Library (Slovanská knihovna) in Prague.

Word Count: 6

I would like to thank the representatives of the Slavonic Library (Slovanská knihovna) in Prague for helping me tremendously during my work at the library.

Word Count: 25

- Istanbul

- Ekaterina Aygün. "Konstantinopol’skiy Kommercheskiy Klub." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2949/object/5145-10703476, last modified: 15-09-2021.

-

V.P.-Tch.PainterScene DesignerMuralistIstanbul

Painter V.P.-Tch. is perhaps the most mysterious figure of all Russian-speaking émigré painters who lived in Constantinople in the 1920s. Until now, almost all sources indicated only his initials.

Word Count: 31

Leonid TomiloffScene DesignerDecoratorIstanbulAs a professional scene-designer, Leonid Tomiloff was in high demand in Istanbul. For many years, he worked at the Theatre des Petits Champs and was the chief decorator of the Constantinople Commercial Club.

Word Count: 33

Dimitri IsmailovitchPainterArt HistorianIstanbulIn Istanbul, Ismailovitch became one of the leaders of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, organised three solo exhibitions, and made contribution to the study of Byzantine art.

Word Count: 29

Nikolai KalmykoffPainterScene DesignerMuralistIstanbulKalmykoff played an active part in the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople and at the same time worked as a stage designer. Later he acquired the Turkish citizenship.

Word Count: 29

Nikolai SaraphanoffPainterIllustratorIstanbulThe artist is known for his numerous works with views of Istanbul, the design of the famous almanac’s cover, and the creation of decorative panels. Alas, his artistic activities were interrupted by his imprisonment.

Word Count: 35

Roman BilinskiPainterSculptorCollectorArt restorerIstanbulAt the beginning of the 1920s, a member of the Union of Russian Painters in Constantinople, Roman Bilinski was known as a sculptor. At the end of the 1920s–beginning of the 1930s – as a sculptor, painter and connoisseur of local antiques.

Word Count: 42