Archive

Willy Haas

- Willy

- Haas

Vilém Haas

- 07-06-1891

- Prague (CZ)

- 04-09-1973

- Hamburg (DE)

- EditorScript WriterCultural Critic

The former editor of Die Literarische Welt fled to Bombay in 1939. In India Haas worked as scriptwriter for Bhavnani Productions – and had further impact on modern Indian film.

Word Count: 28

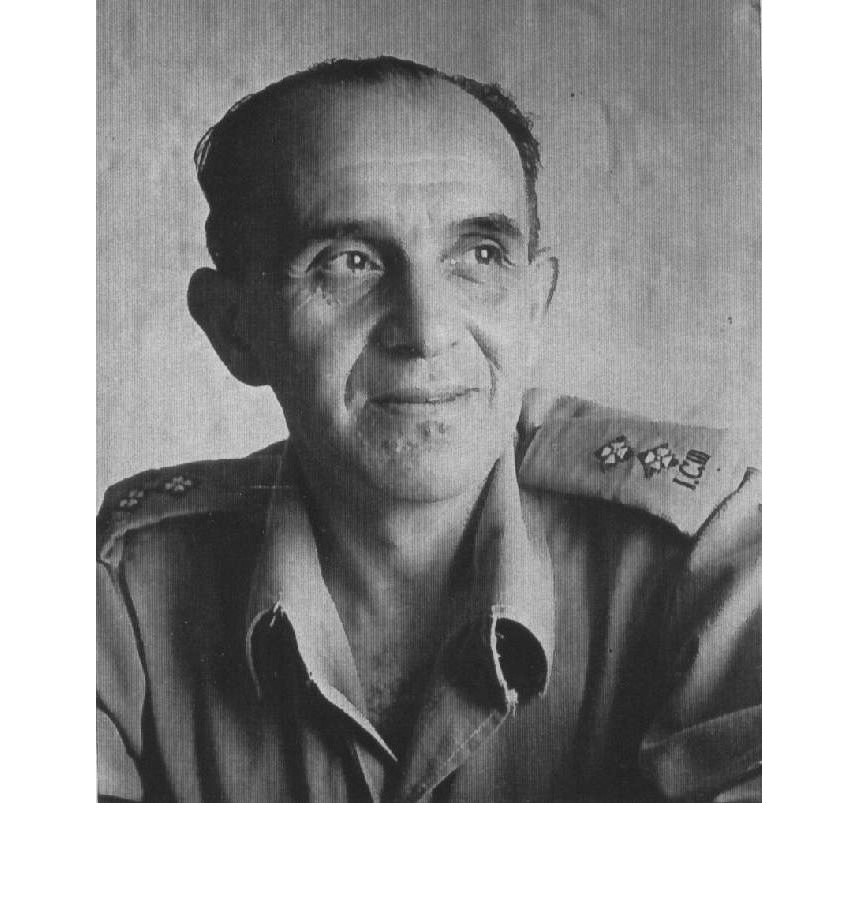

Portrait of Willy Haas as censor of the British Indian army, n.d. (Repro by the author from the collection of Dr. Herta Haas/ now Schiller Nationalmuseum/Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach am Neckar).

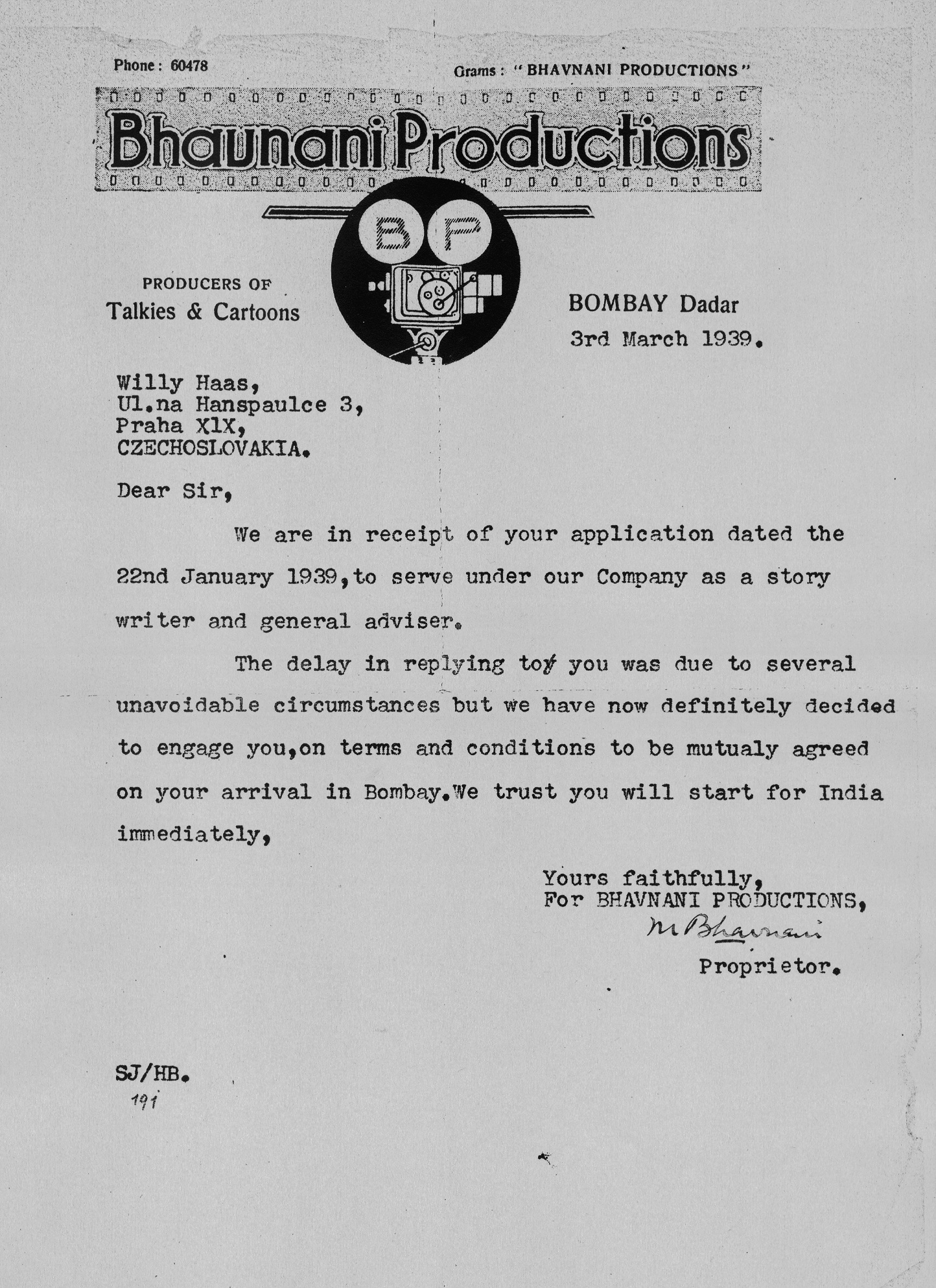

Letter of intent to employ Willy Haas at Bhavnani Productions, 3 March 1939 (Repro by the author from the collection of Dr. Herta Haas/ now Schiller Nationalmuseum/Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach am Neckar).

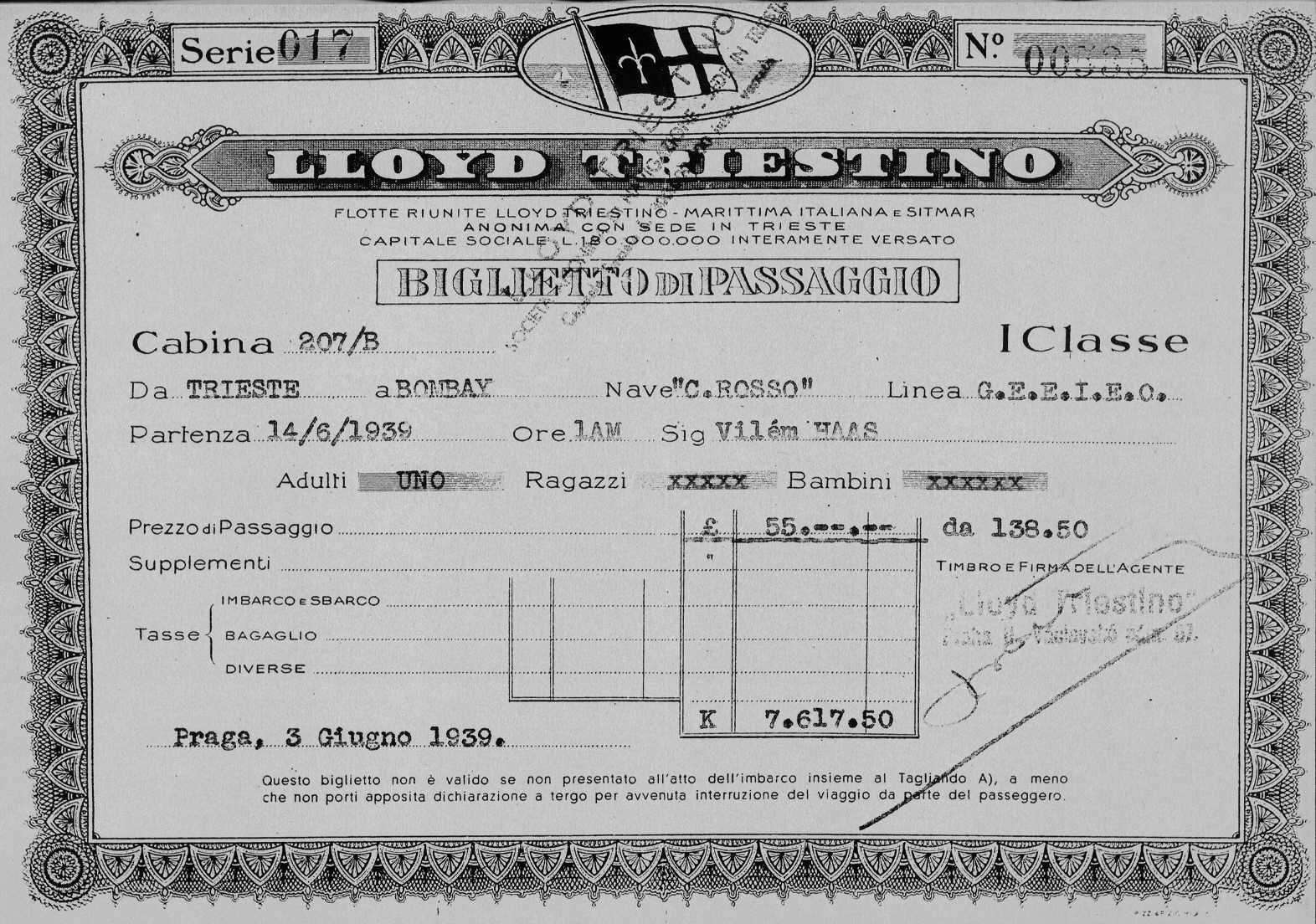

Willy Haas’s ticket for the passage to India on the SS Conte Rosso, 1939 (Repro by the author from the collection of Dr. Herta Haas/ now Schiller Nationalmuseum/Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach am Neckar).

Scene from the movie Prem Nagar directed and produced by M. Bhavnani, 1941 (Screenshot by the author from a copy by the National Film Archive of India/courtesy of Famous Cine Laboratory).

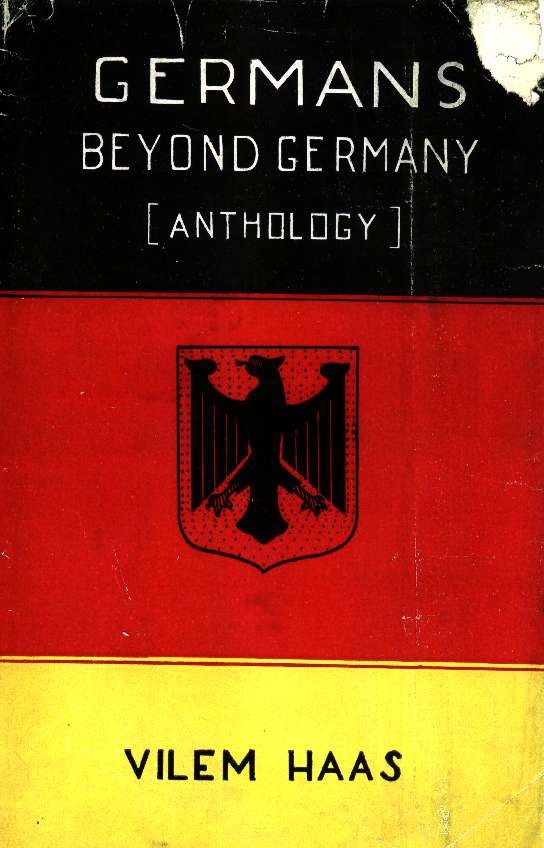

Book jacket of Germans beyond Germany. Bombay: International Book House, 1942 (Repro by the author from the collection of Dr. Herta Haas/ now Schiller Nationalmuseum/Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach am Neckar). Haas, Vilem, editor. Germans Beyond Germany. Translated by Hetty Kohn, The International Book House Bombay, 1942. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.103360. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Haas, Vilem [Willy]. “On Teaching German Literature I“. The Punjab Educational Journal, vol. XXXIX, no. 4, July 1944, pp. 247–254.

Haas, Vilem [Willy]. “On Teaching German Literature II“. The Punjab Educational Journal, vol. XXXIX, no. 5, August 1944, pp. 274–278.

Haas, Vilem [Willy]. “On Teaching German Literature III“. The Punjab Educational Journal, vol. XXXIX, no. 6, September 1944, pp. 301 –308.

Haas, Vilem [Willy]. “On Teaching German Literature IV“. The Punjab Educational Journal, vol. XXXIX, no. 7, October 1944, pp. 333 –336.

Haas, Willy. Die Literarische Welt. Erinnerungen. P. List, 1957. [Translations by the author]

Ungern-Sternberg, Christoph von. Willy Haas 1891-1973. “Ein grosser Regisseur der Literatur”. edition text + kritik, 2007.

Word Count: 120

Collection of Dr. Herta Haas, Hamburg (now Schiller Nationalmuseum/Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach am Neckar).

National Film Archive of India, Pune.

Schiller Nationalmuseum/Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach am Neckar.Word Count: 27

Bombay, India (1939−1941); Dehra Doon, India (1941−1947); London, UK (1947−1948).

Bhavnani Productions, 104, Main Rd, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West, Bombay (now Mumbai)(studio 1939−1941); Soona Mahal, Marine Drive, Bombay (now Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Rd Churchgate, Mumbai) (residence 1939−1941).

- Bombay

- Christoph von Ungern-Sternberg. "Willy Haas." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2951/object/5138-12032691, last modified: 15-09-2021.

-

Paul ZilsFilmmakerBombay

Paul Zils became a central figure in the realm of the Indian documentary film history. Before his emigration to Bombay in 1945, he had worked at Ufa in Germany.

Word Count: 28

Lesser’s Boarding HouseHotelGerman Jewish boarding houseBombayDuring the 1940’s Max Lesser ran one of the very few German-Jewish boarding houses in Bombay – in the art deco “Soona Mahal” on Marine Drive.

Word Count: 25

Jewish Relief Association BombayRelief OrganisationBombayIn 1934, the first refugees from National Socialism founded a Jewish aid association in Bombay called the Jewish Relief Association (JRA) to help refugees in financial and other difficulties.

Word Count: 28

Walter KaufmannComposerConductorMusicologistTeacherBombayThe 12-year exile in Bombay shaped Walter Kaufmann’s life and work; his signature tune for All India Radio is played till today.

Word Count: 23