Archive

Magda Nachman Acharya

- Magda

- Nachman Acharya

Magda Nachman

- 20-07-1889

- Saint Petersburg (RU)

- 12-02-1951

- Mumbai (IN)

- ArtistTheatre DesignerIllustratorTeacher

The political turmoil of the twentieth century took Magda Nachman from St. Petersburg to Moscow to the Russian countryside, then to Berlin during the 1920s and 1930s and, finally, to Bombay.

Word Count: 31

Photo of Magda Nachman Acharya in front of her house on Malabar Hill, n.d., detail (Courtesy of Sophie Seifalian, All Rights Reserved).

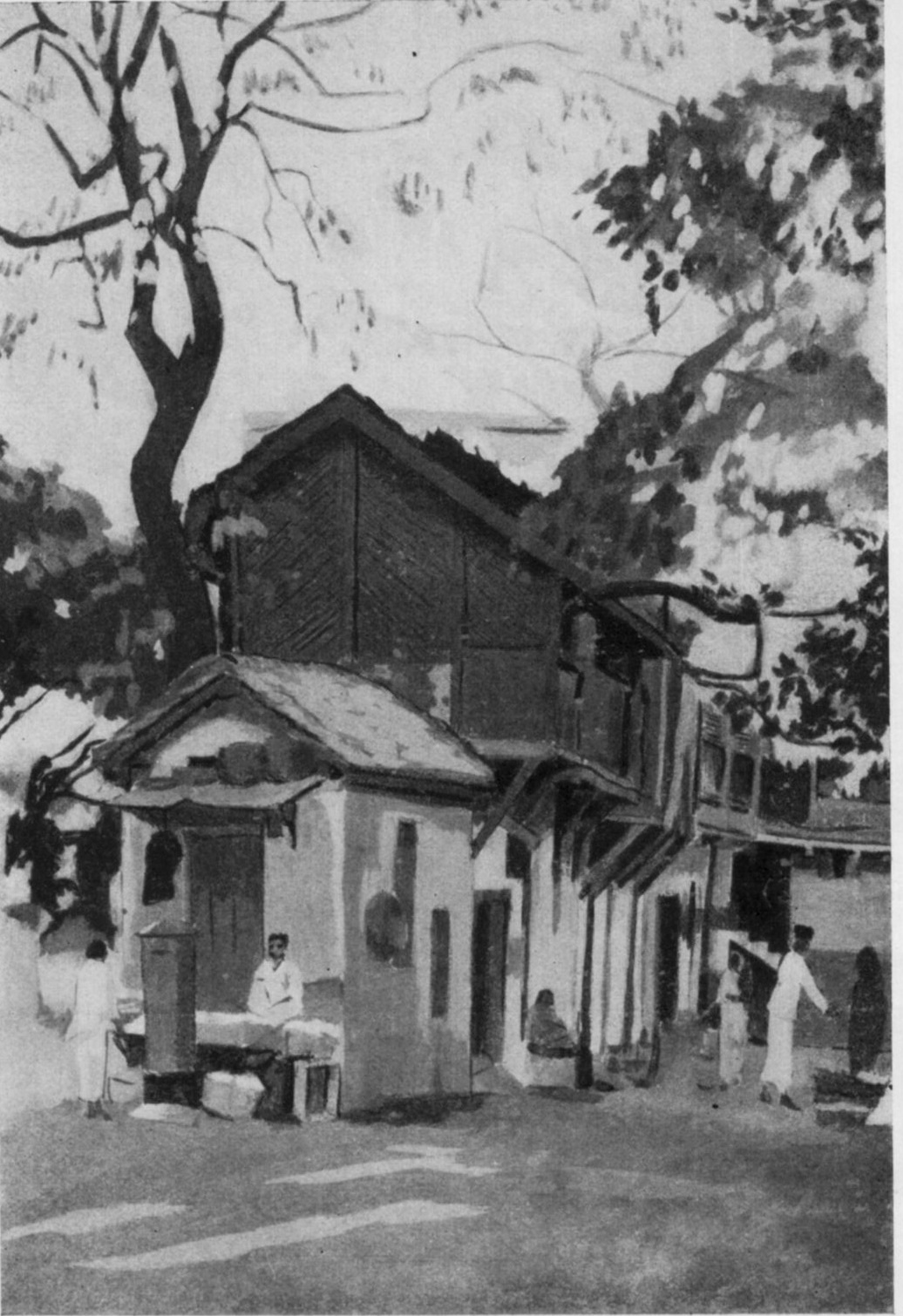

Magda Nachman Acharya, City landscape, around 1937, exh. cat. The Bombay Art Society, Bombay, 1937, p. 13 (Photo: Lina Bernstein 2014).

Magda Nachman Acharya, A portrait of Kamal Wood, around 1944 (© Private collection, USA, All Rights Reserved).

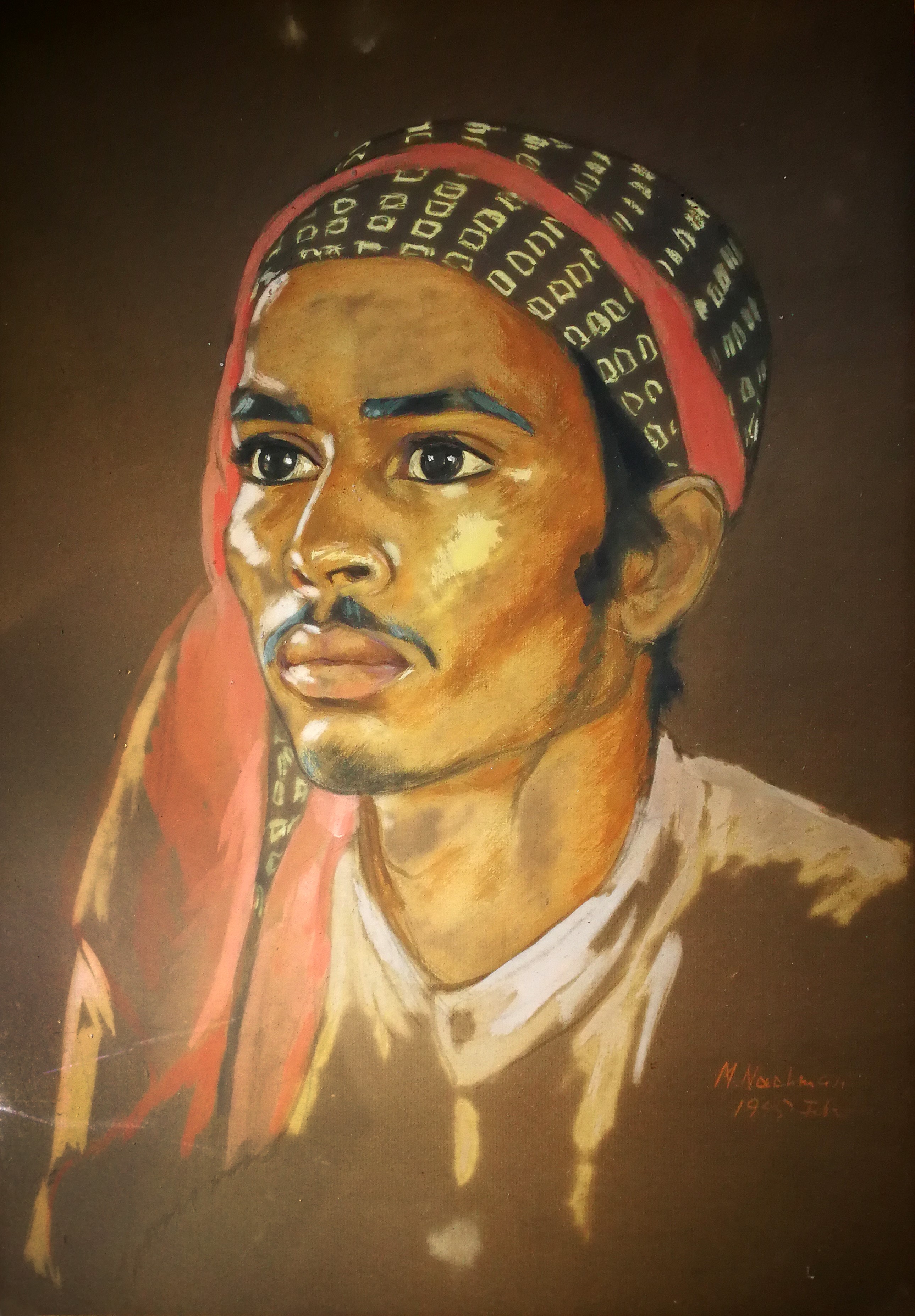

Magda Nachman Acharya, A Young Man, 1945 (© Private collection, Israel, All Rights Reserved).

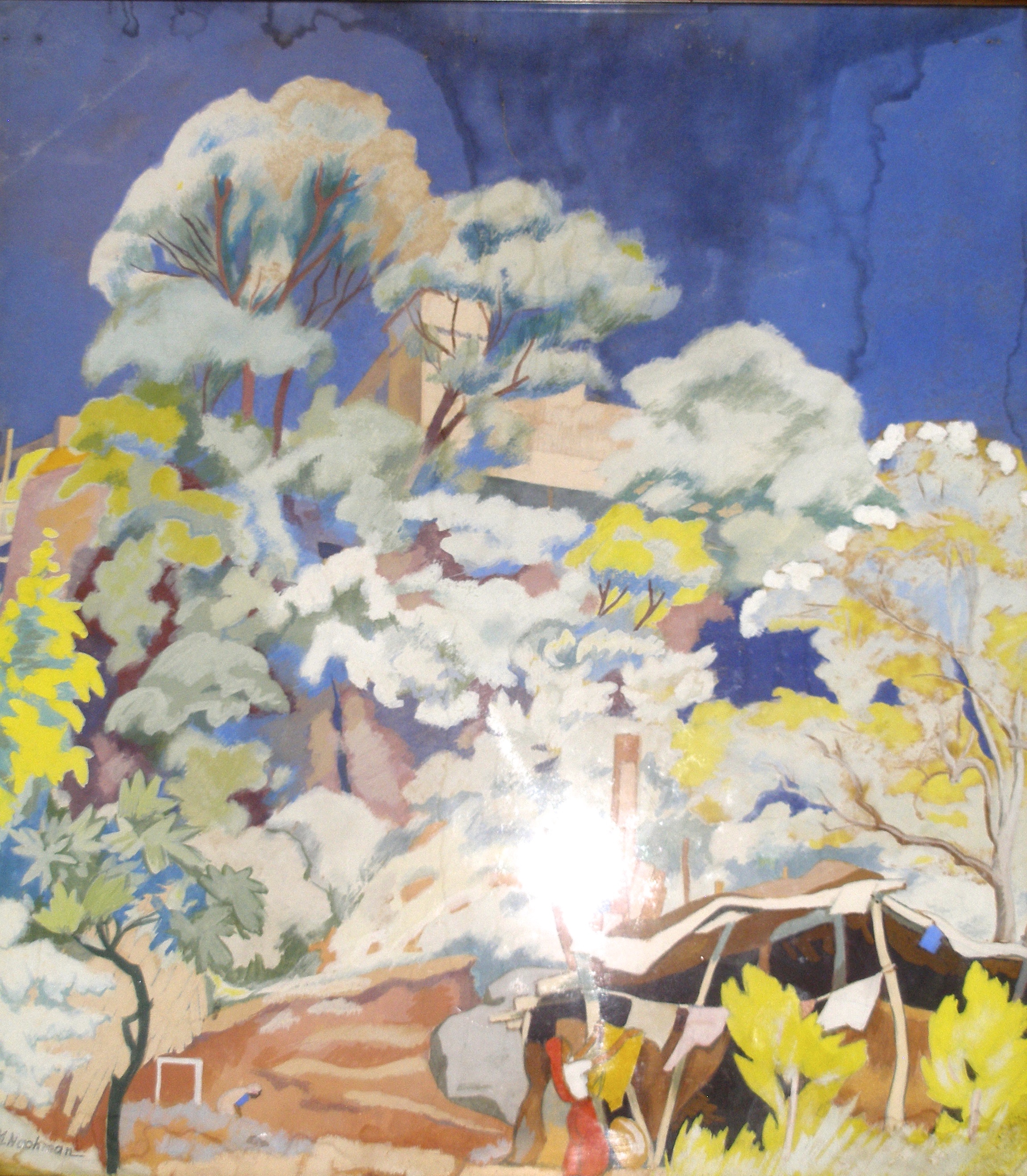

Magda Nachman Acharya, Landscape in Matheran, 1945 (© Roshan Cooper collection, Pune, All Rights Reserved). Bernstein, Lina. Magda Nachman: An Artist in Exile (Modern Biographies). Academic Studies Press, 2020.

Word Count: 13

For more images of works by Magda Nachman and a more detailed account of her life, please visit the online exhibition in the State Museum of Oriental Cultures in Moscow, Russia (open through September 2023).

Word Count: 34

Bombay, India (1936–1951)

56 Ridge Road, Malabar Hill, Bombay (now Mumbai); 63 Walkeshwar Road, Malabar Hill, Bombay (now Mumbai).

- Bombay

- Lina Bernstein. "Magda Nachman Acharya." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2951/object/5138-7555976, last modified: 06-09-2021.

-

Hilde HolgerChoreographerDancerTeacherBombay

Hilde Holger brought her expressionist dance practice from Vienna to Bombay, collaborating with local and exile artists, and opening a dance school.

Word Count: 22

TIFRUniversity / Higher Education Institute / Research InstituteBombayThe TIFR is one of India’s premier scientific institutions. Inside its buildings, scientists ponder over path-breaking ideas. Also, within its hallowed walls is a fine collection of modern Indian art.

Word Count: 31

Institute of Foreign LanguagesLanguage SchoolExhibition SpaceLibraryTheatreBombayWith its wide range of cultural activities, the Institute of Foreign Languages − founded in 1946 by the Viennese emigrant Charles Petras − became a glocal contact zone in Bombay.

Word Count: 27

Bombay Art SocietyAssociationBombayOne of the oldest art societies in India founded by colonial rulers, Bombay Art Society showcased art students and professional artists from all over India, including the Progressive Artists of Bombay.

Word Count: 31

Rudolf von LeydenGeologistAdvertisement SpecialistJournalistArt CriticArt CollectorCartoonistBombayThe advertisement expert, Rudolf von Leyden, became a major art critic and art historian in Bombay in the 1940s, advocating an urgent need for modernism in art in post-colonial India.

Word Count: 30