Archive

Jewish Relief Association Bombay

- Jewish Relief Association Bombay

JRA

- Relief Organisation

In 1934, the first refugees from National Socialism founded a Jewish aid association in Bombay called the Jewish Relief Association (JRA) to help refugees in financial and other difficulties.

Word Count: 28

1941: E. D. Sassoon Building, 4th floor, Dougall Road, Ballard Estate, Bombay (now 15, N Morarji Rd, Ballard Estate, Fort Mumbai);

1963: Hague Building, 2nd floor, Sprott Road, Ballard Estate, Bombay (now SS Ram Gulam Marg, Ballard Estate, Fort, Mumbai).

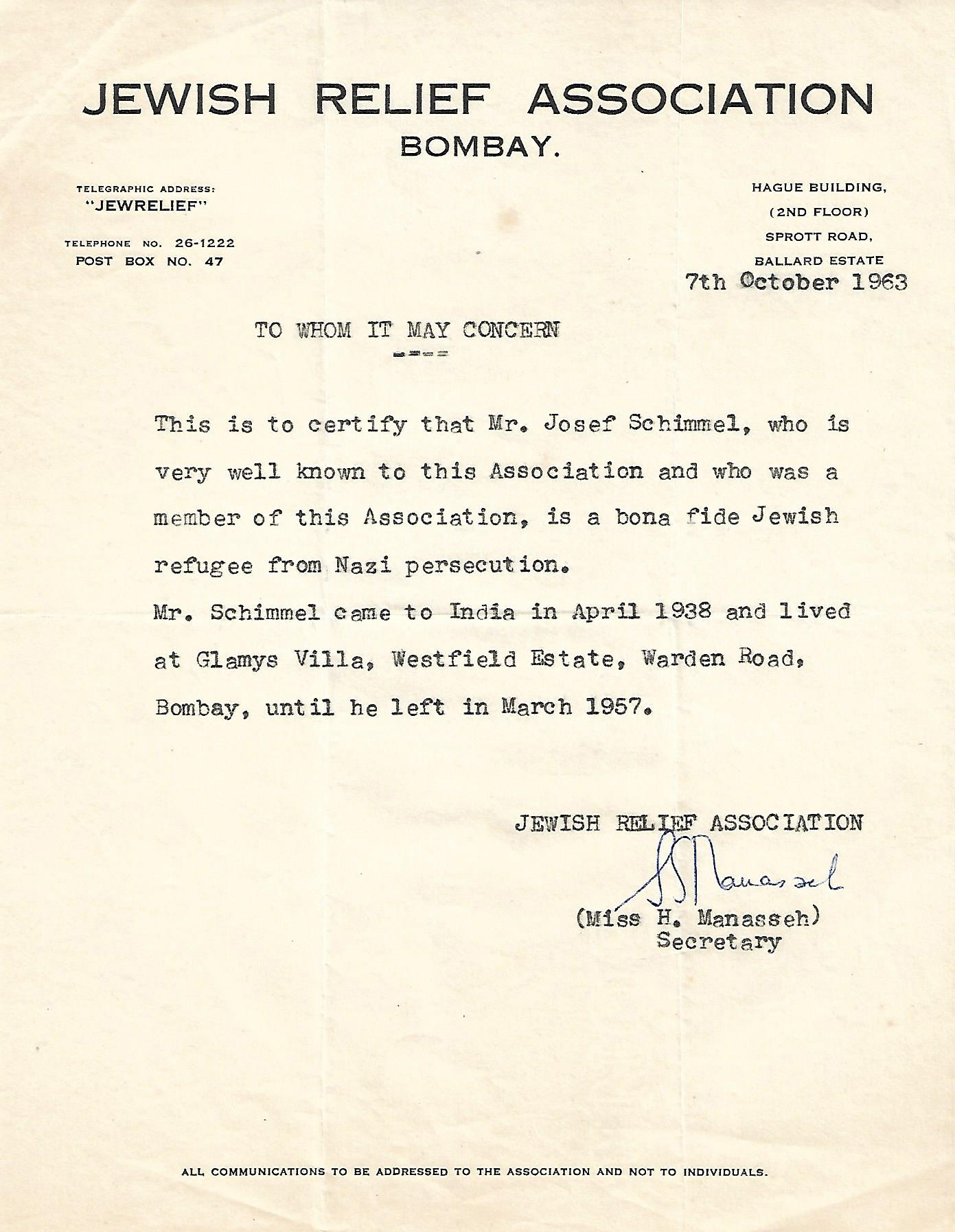

Letter from the Jewish Relief Association confirming active membership to Joe Schimmel during his years in India (© Private Archive Joe Schimmel, Cape Town).

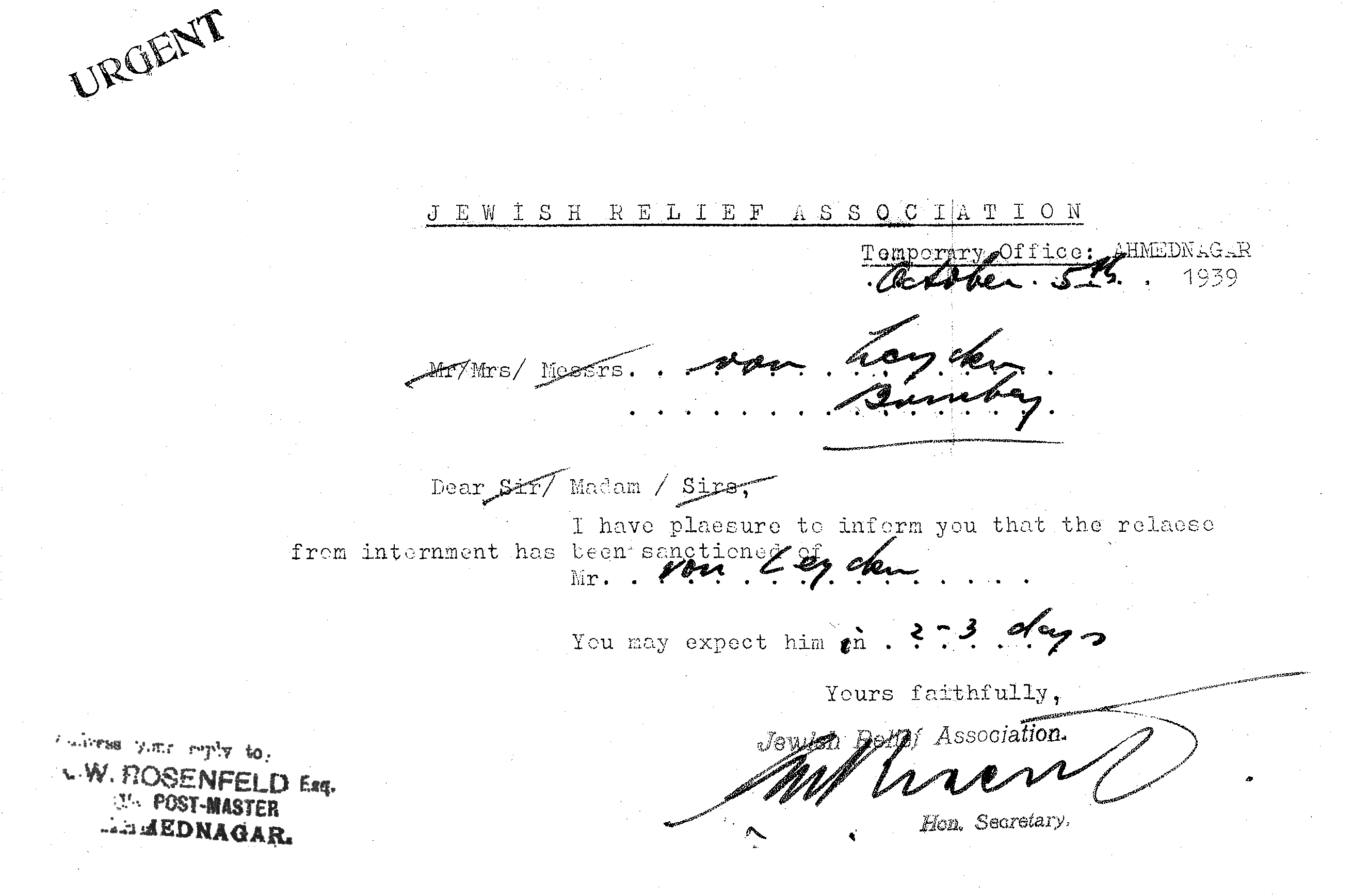

JRA announcement of the release of Victor von Leyden from internment on 5 October, 1939 (© Private Archive Flora Veit-Wild, Berlin).

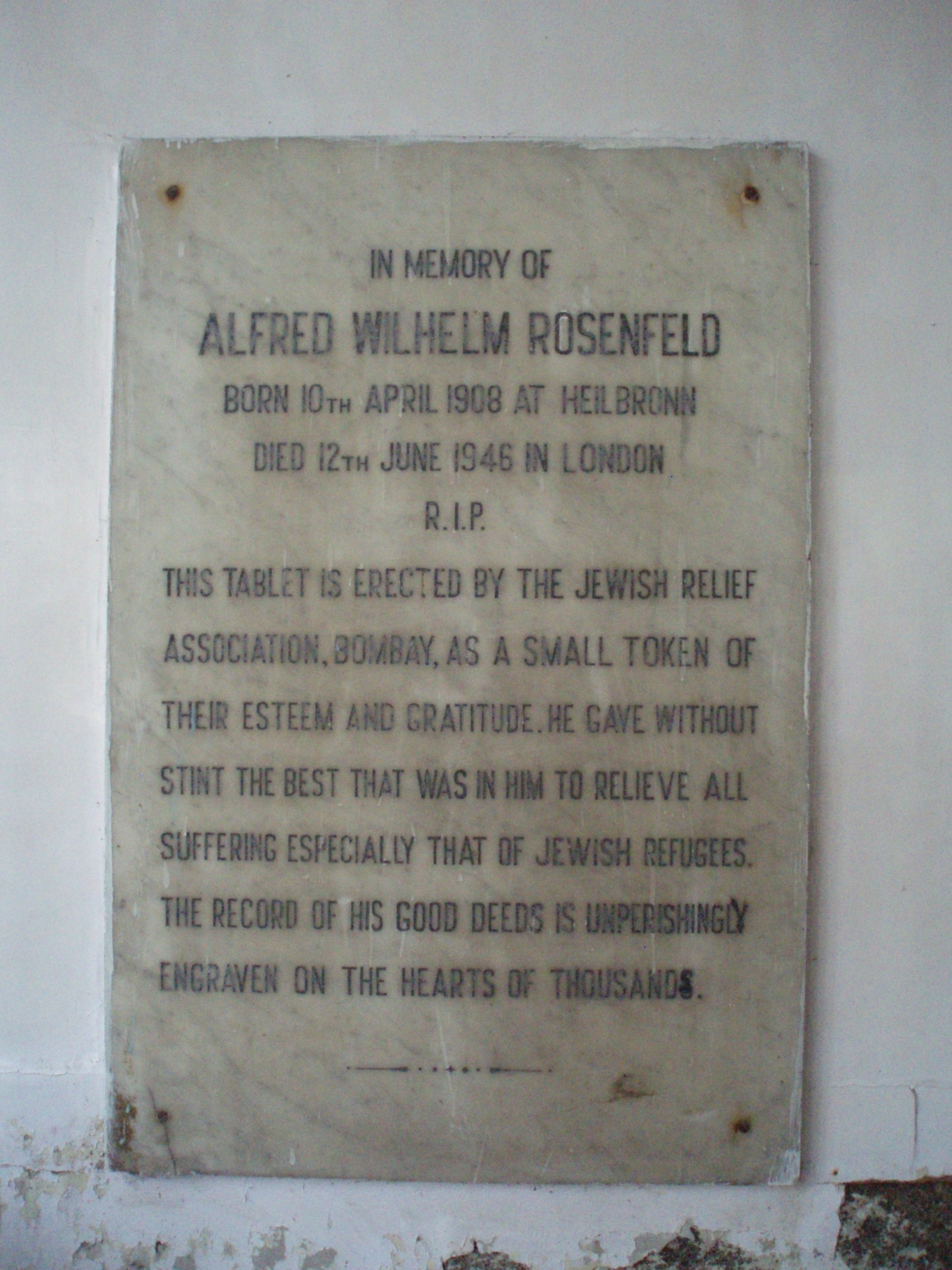

Memorial plaque for Alfred W. Rosenfeld at the Chinchpokli Jewish cemetery in Mumbai, 2010 (Photo: Margit Franz; All Rights Reserved). Bergwerk, Walter. “Seder in Bombay 1944.” AJR Journal, vol. 11, no. 5, May 2011, p. 3, ajr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2011_May.pdf. Accessed 25 April 2021.

Franz, Margit. Gateway India: Deutschsprachiges Exil in Indien zwischen britischer Kolonialherrschaft, Maharadschas und Gandhi. CLIO, 2015.

Kahn, Henry H. “The Silver Candle Holders: Autobiography and Background of Henry H. Kahn. Bethesda, 2005.” (unpublished autobiography, Leo Baeck Institute, Center for Jewish History, New York, 2005), digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE9059690#1. Accessed 11 April 2021.

Voigt, Johannes H. “Indien.” Handbuch der deutschsprachigen Emigration 1933–1945, edited by Claus-Dieter Krohn et al., Primus, 1998, column 270–275.

Weil, Shalva. “From Persecution to Freedom: Central European Jewish Refugees and their Jewish Host Communities in India.” Jewish Exile in India 1933–1945, edited by Anil Bhatti and Johannes H. Voigt, Manohar, 1999, pp. 64–86.

Word Count: 118

Private Archive Margit Franz, Sinabelkirchen.

Private Archive Joe Schimmel, Cape Town.

Private Archive Flora Veit-Wild Archive, Berlin.Word Count: 17

- 1934

Prof. Dr. Oscar Gans (1888–1983), Alfred W. Rosenfeld (1908–1946), Ernst Alexander Lomnitz, Karl Maximilian Feil, Gerhard Gabriel, Max Lesser, Hanns Günther Reissner, Hans S. Grossmann (1902–1974), Joe Schimmel, Käthe Langhammer.

- Bombay

- Margit Franz. "Jewish Relief Association Bombay." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2951/object/5145-11945043, last modified: 14-09-2021.

-

Emanuel SchlesingerFactory OwnerTechnical DirectorArt CollectorArt CriticBombay

The art collector Schlesinger provided primarily financial aid by creating working opportunities for young artists in post-independence Bombay, and initiated the corporate culture of buying art.

Word Count: 26

Willy HaasEditorScript WriterCultural CriticBombayThe former editor of Die Literarische Welt fled to Bombay in 1939. In India Haas worked as scriptwriter for Bhavnani Productions – and had further impact on modern Indian film.

Word Count: 28

Ernst N. SchaefferJournalistPhotojournalistTour GuideEditorRadio ModeratorNewspaper CorrespondentBombayIn exile Ernst Schaeffer diversified his journalistic practice and developed an understanding of Bombay through walking the city streets, taking on street-level-photography and photojournalism.

Word Count: 24

Baumgartner’s BombayBookBombayThe novel Baumgartner’s Bombay provides an opposite picture to that of the successful refugee in Bombay. Anita Desai’s fiction depicts poverty and failure in Indian exile.

Word Count: 28

Lesser’s Boarding HouseHotelGerman Jewish boarding houseBombayDuring the 1940’s Max Lesser ran one of the very few German-Jewish boarding houses in Bombay – in the art deco “Soona Mahal” on Marine Drive.

Word Count: 25