Archive

https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2952/object/5140-11304821

Archive

Ward Road Gaol; Tilanqiao Prison

- Building

Ward Road Gaol; Tilanqiao Prison

Word Count: 5

- Tilanqiao Prison

- 1934

Ward Road, Hongkou (now Changyang Lu, corner of Zhoushan Lu, Hongkou Qu) Shanghai

- Shanghai (CN)

The Ward Road Gaol (today Tilanqiao Prison) had space for 7000 prisoners.The rather small new extension for foreign prisoners designed by the architect Rudolf Hamburger consisted of two buildings and a pavilion for the guards.

Word Count: 35

Ward Road Gaol, interior, photography, Shanghai (© Hamburger family). The guards are able to see all areas from the aisles.

Ward Road Gaol, photography, Shanghai (© Hamburger family). The men’s building has six floors and a usable roof area.

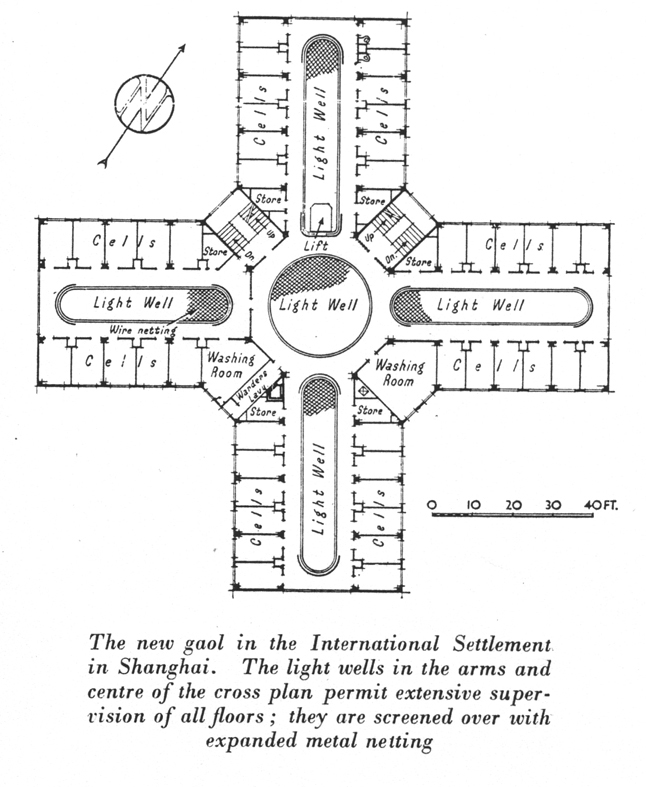

Ward Road Gaol Shanghai, floor plan, (© Hamburger family). It shows a typical cruciform floor plan.

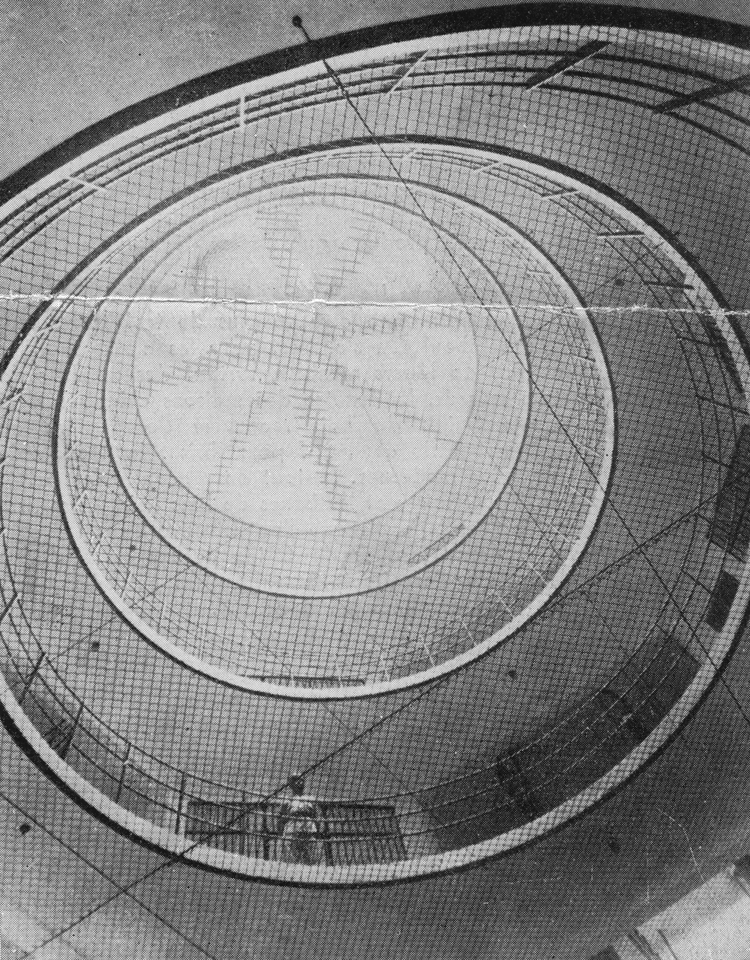

Ward Road Gaol, photography, Shanghai (© Hamburger family). The central round light source, which was covered with a glass dome.

Ward Road Gaol, interior, photography, Shanghai (© Hamburger family). The guards are able to see all areas from the aisles. Dikötter, Frank. Crime, Punishment and the Prison in Modern China. Columbia University Press, 2002.

Kögel, Eduard. Architekt im Widerstand. Rudolf Hamburger im Netzwerk der Geheimdienste. DOM Publisher, 2020.

Kögel, Eduard. Zwei Poelzigschüler in der Emigration: Rudolf Hamburger und Richard Paulick zwischen Shanghai und Ost-Berlin (1930–1955). University of Weimar, 2006, toi: https://doi.org/10.25643/bauhaus-universitaet.929.Word Count: 54

- Shanghai

- Eduard Kögel. "Ward Road Gaol; Tilanqiao Prison." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2952/object/5140-11304821, last modified: 20-06-2021.

-

Victor SassoonEntrepreneurShanghai

Victor Sassoon was a descendant of the Baghdadi Jewish Sassoon merchant family. He contributed significantly to a real estate boom in Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s and helped European Jews in the Shanghai Ghetto. An ambitious amateur photographer, he produced many images of people and events of the time.

Word Count: 50

Hubertus CourtPrintShanghaiThe print was made by the artist Emma Bormann during her exile in Shanghai in the 1940s.The title suggest that the print offers a bird’s eye view from the Hubertus Court building.

Word Count: 34