Archive

David Ludwig Bloch

- David

- Ludwig

- Bloch

Bai Lühei

- 15-03-1910

- Floß (DE)

- 16-09-2002

- Red Hook (US)

- Artist

David Ludwig Bloch is known for his paintings and watercolours revolving around the Holocaust and his exile. With the woodcuts from his time in exile in Shanghai, Bloch created an artistic account of everyday life in the city, while harvesting the simplicity of form and colour of the medium.

Word Count: 49

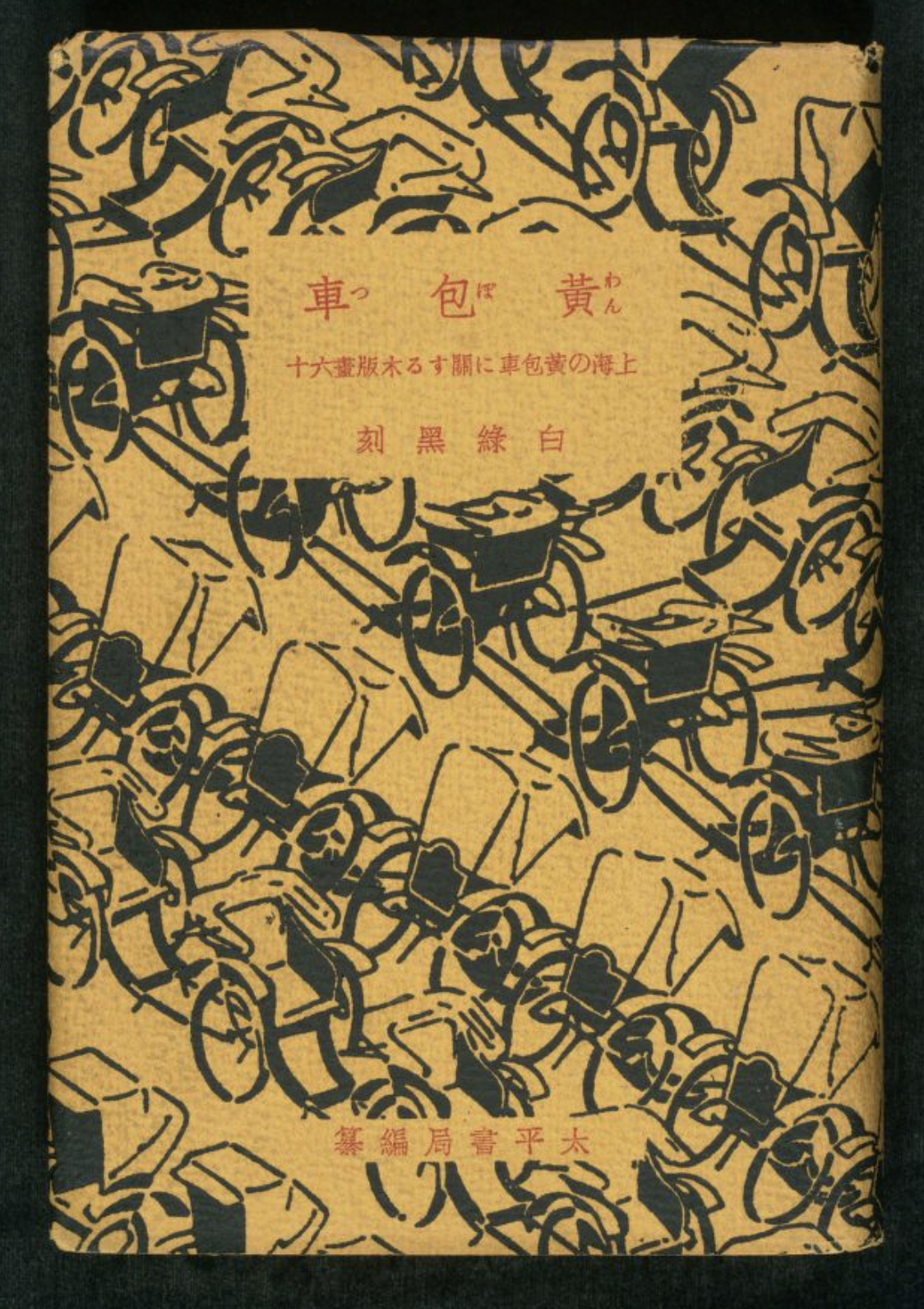

David Ludwig Bloch, Rickshaw, book of woodcuts, cover, ink on paper, 20 cm x 14 cm, 1945, Taiping Yinshua Gongsi, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

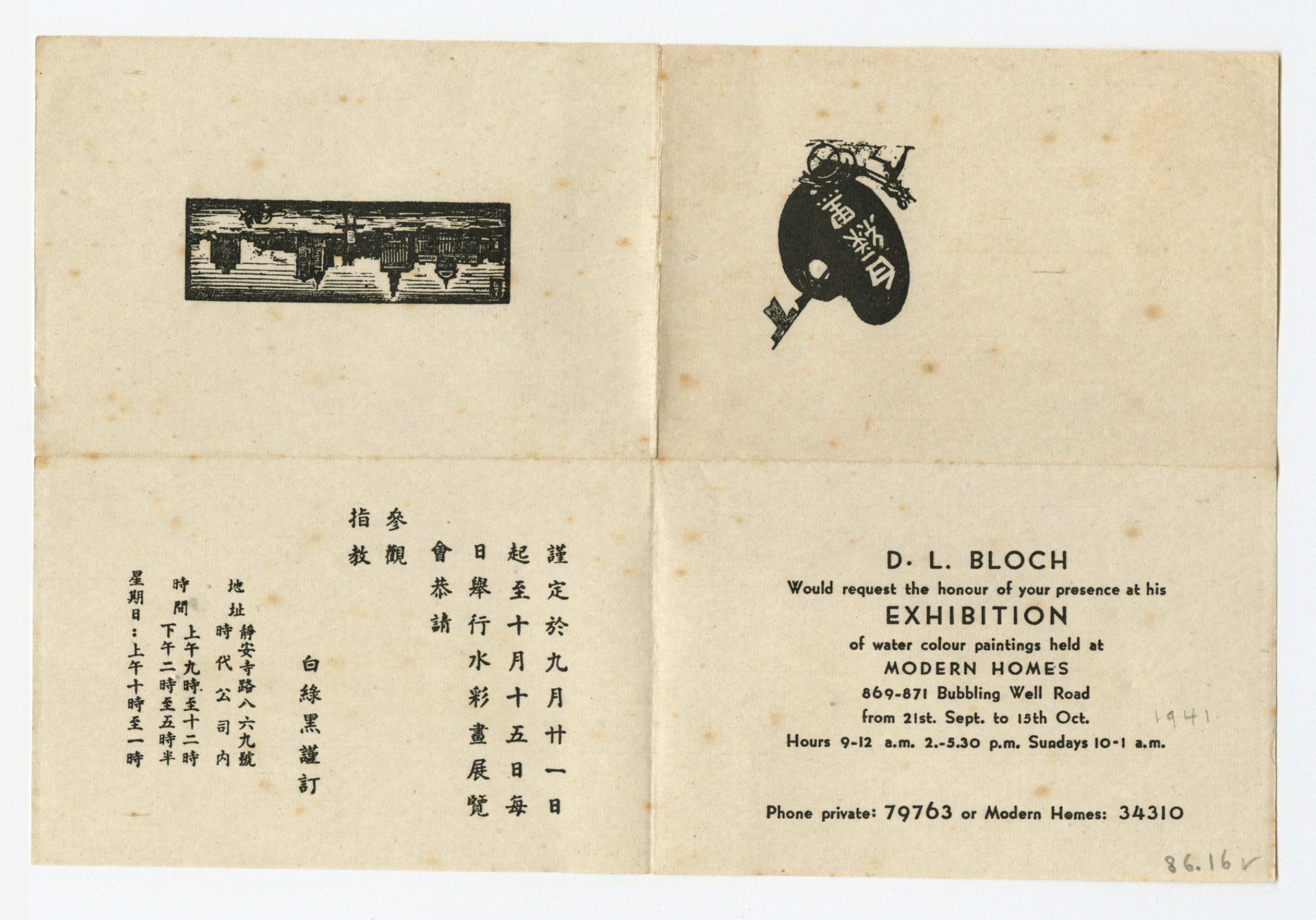

David Ludwig Bloch, Invitation to Bloch's exhibition of watercolors, linotype, 16.5 x 25 cm, 1941, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

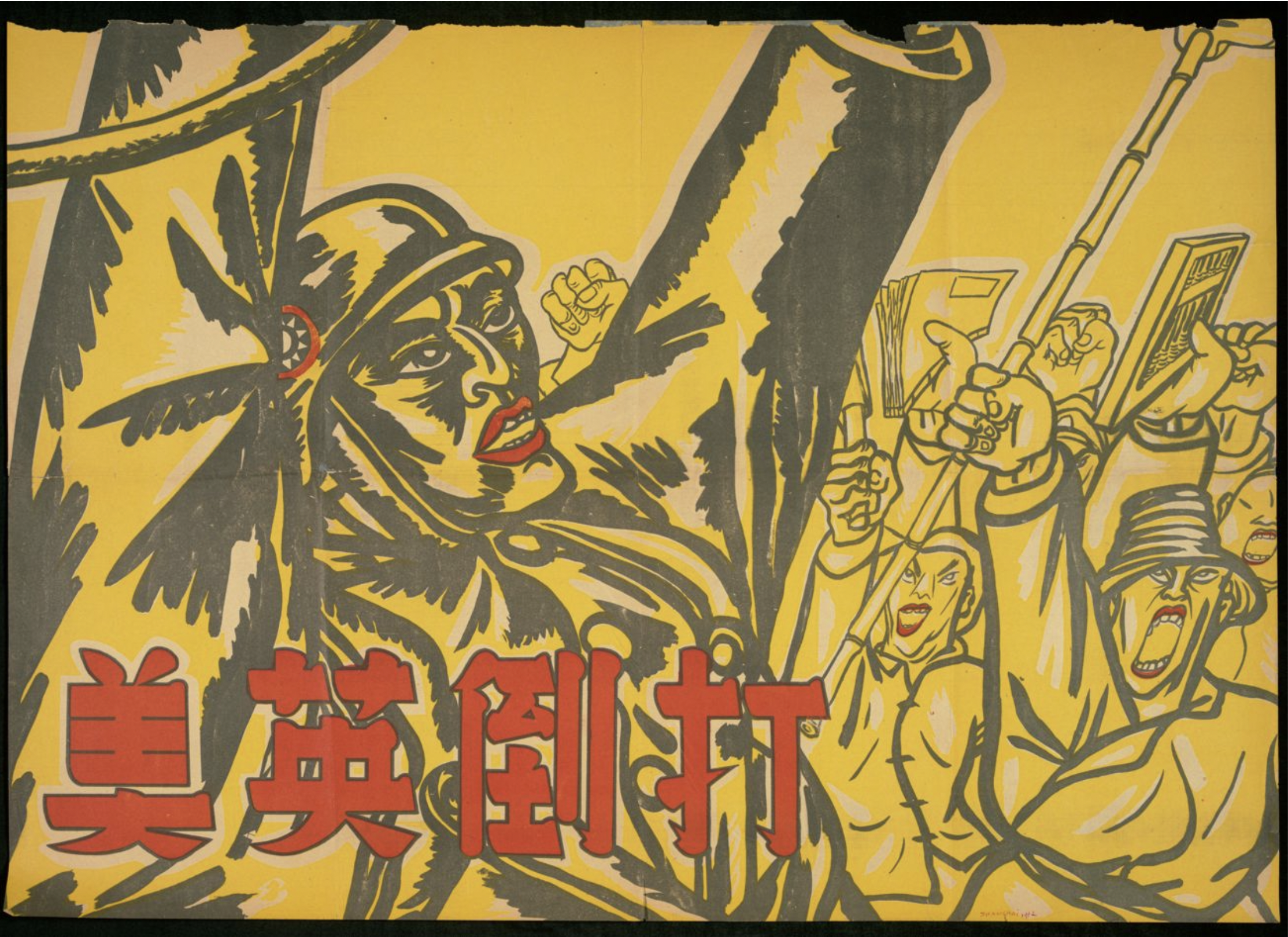

David Ludwig Bloch, Shanghai Soldier, woodcut, ink on paper, 53.3 cm x 76.2 cm, 1942, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

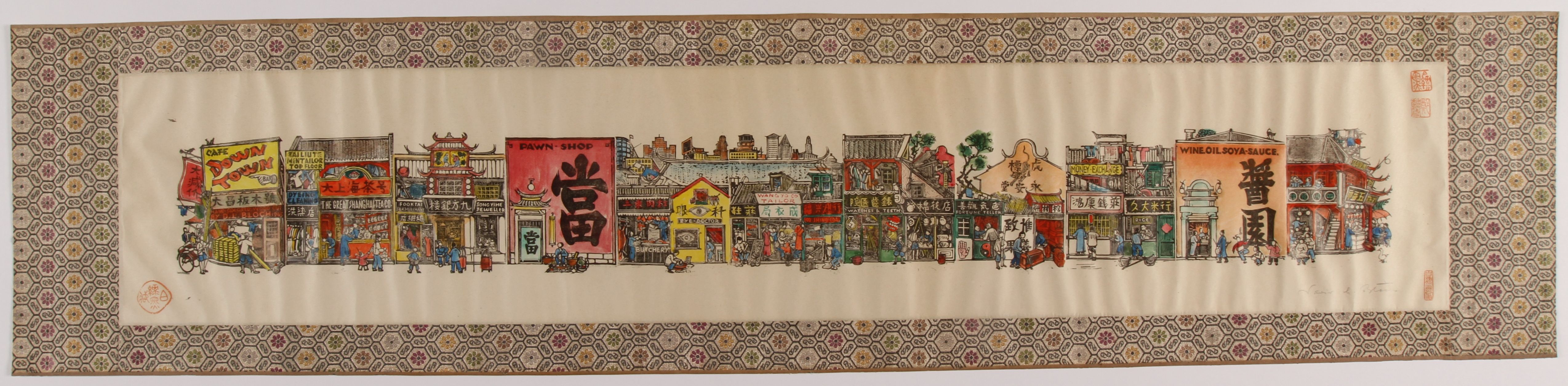

David Ludwig Bloch, Chinese Street Scene–Shanghai, hand colored woodcut, matted with Chinese silk, Shanghai 1945 (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of David L. Bloch).

David Ludwig Bloch, Shanghai Street, woodcut, hand tinted, matted with Chinese silk, framed in gilded bamboo, 105 x 27 cm, 1945, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York). This print was signed for Hans Jacoby.

David Ludwig Bloch, Shanghai, Street Scene, watercolor on paper, 39 x 57 cm, 1949, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

David Ludwig Bloch, Yin and Yang, book of 48 woodcuts, street scene, ink on paper, 21,1 x 18,4 cm, 1948, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

David Ludwig Bloch, Yin and Yang, book of 48 woodcuts, Wing Hon Coffin Co., ink on paper, 21,1 x 18,4 cm, 1948, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York).

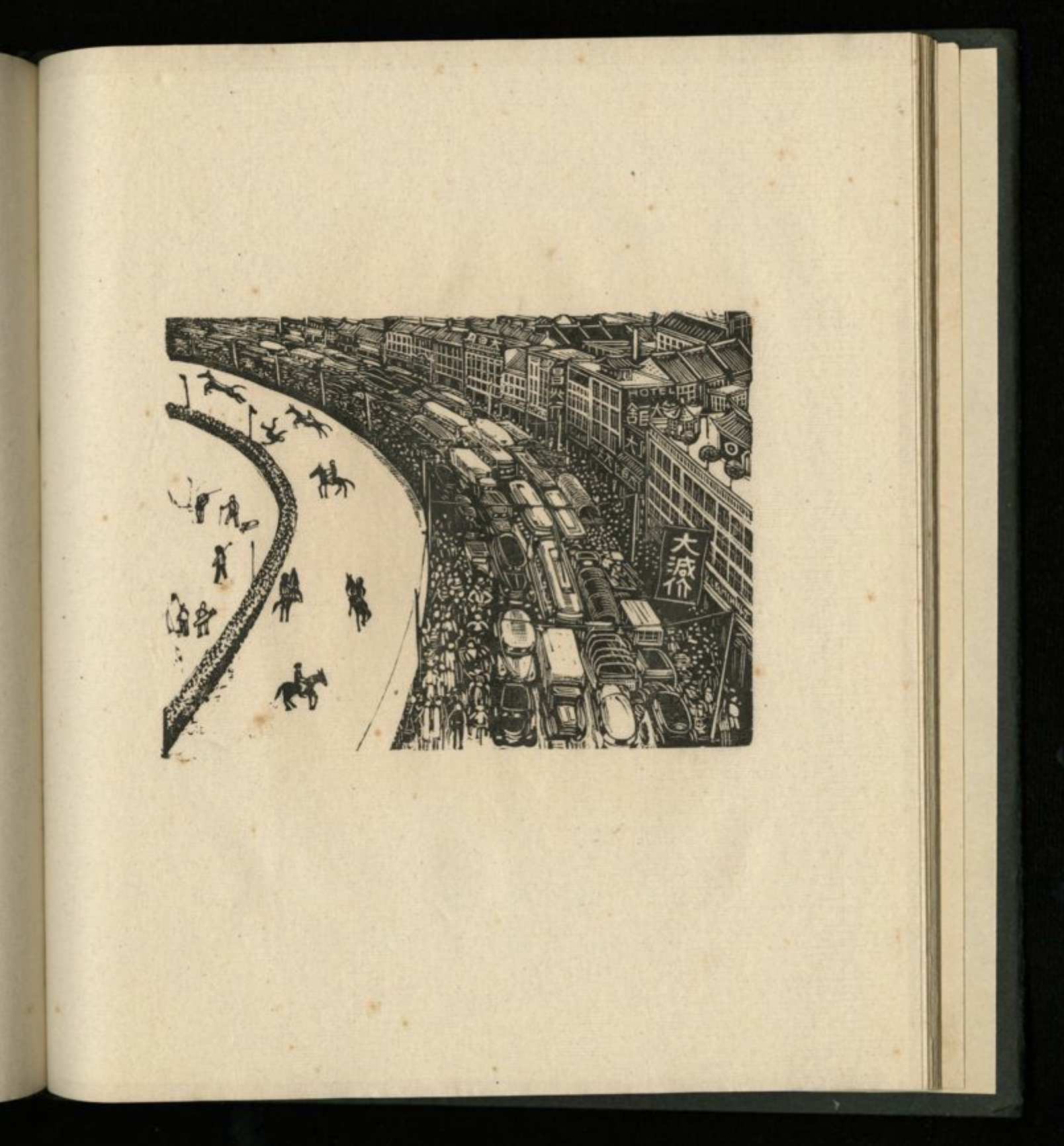

David Ludwig Bloch, Yin and Yang, book of 48 woodcuts, Race Course, ink on paper, 21,1 x 18,4 cm, 1948, Shanghai, David Ludwig Bloch Collection (© Leo Baeck Institute, New York). While many of Block's prints show details and small sections of street life, this is one of those that capture a wide urban space from an elevated perspective. This print is reminiscent of those by Emma Bormann.

Sax-Darnous. "Houang Pao Tch'ô." Revue National Chinoise, vol. 22, no. 156, 1946, pp. 56–57. This article was published on the occasion of Bloch's book Rickshaw.

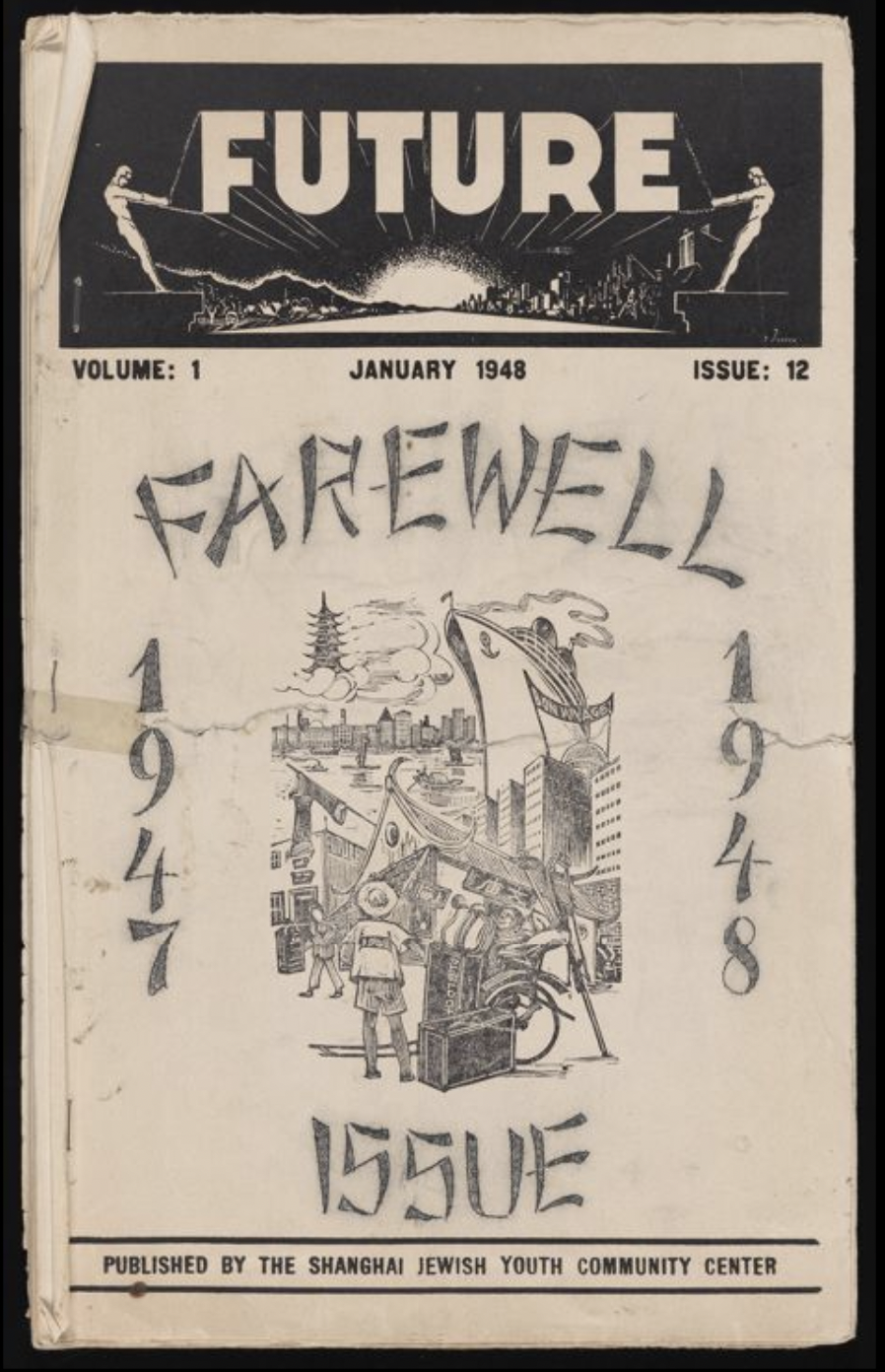

Future, vol. 1, no. 12, January 1948, series 5, printed materials, 1939–1988, Future, 1948, John and Harrier Isaack papers (© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of John and Harriet Isaack). Published by the Shanghai Jewish Youth Community Center. Cover lettering print by John Isaack, cover print by David Ludwig Bloch. Last issue “our magazine has served as a binding link between those of our members who have gone abroad and those who will remain in Shanghai.” Hoster, Barbara and Malek Roman (editors). David Ludwig Bloch: Holzschnitte Shanghai 1940–1949, Steyler, 1997.

Neugebauer, Rosamunde. Zeichnen im Exil - Zeichen des Exils? Handzeichnung und Druckgraphik deutschsprachiger Emigranten ab 1933. VDG 2003.

Brieger, Lothar. "David Ludwig Bloch kommt nach USA." Der Aufbau, vol. 13, no. 51, 19 December 1947, p. 11.Word Count: 42

Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Kunstsammlung David Ludwig Bloch

Leo Baeck Institute, New York, David Ludwig Bloch CollectionWord Count: 17

Shanghai, China (1940–1949), USA

Rue Maresca, French Concession (now Wuyuan Lu, Xuhui Qu); 24/17 Ward Road, Hongkou (now Changyang Lu, Hongkou Qu), Shanghai (residence and studio)

- Shanghai

- Mareike Hetschold. "David Ludwig Bloch." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2952/object/5138-8100810, last modified: 14-09-2021.

-

Emma BormannArtistShanghai

Emma Bormann was a pioneering artist and printmaker. Her oeuvre gives witness to her extensive travels around the globe and to the agility and versatility of her artistic rendering of the urban sites she encountered.

Word Count: 35

Association of Jewish Artists and Fine Art Lovers (ARTA)AssociationShanghaiSeven Jewish artists living in the so-called Shanghai Ghetto joined together to form an art association in 1943. The founding members were: David Ludwig Bloch, Paul Fischer, Fred Fredden Goldberg, Ernst Handl, Max Heimann, Hans Jacoby and Alfred Mark.

Word Count: 38

Modern HomesArchitecture and Furniture CompanyShanghaiThe three firms The Modern Home, Modern Home and Modern Homes existed from 1931 until 1950. Run by the Paulick brothers together with the Jewish emigrant Luedecke, the firms provided work for many emigrants.

Word Count: 32

Hans JacobyArtistShanghaiHans Jacoby fled in 1938 to the Netherlands, where he was interned by the Dutch government in Hook of Holland. He was able to leave the camp and arrived, together with his wife Emma Jacoby, in Shanghai in 1940 where he continued to work as an artist.

Word Count: 45

Richard PaulickArchitectDesignerShanghaiAfter studying with Hans Poelzig, Richard Paulick worked in Walter Gropius’s office and frequented the Bauhaus in Dessau before emigrating to Shanghai in 1933. After his return, he became an influential planner and architect in the GDR, from 1950 until his retirement

Word Count: 41

Exhibition of prints by Käthe KollwitzExhibitionShanghaiA German woodcut exhibition organised at the Zeitgeist Bookstore presumably took place in June 1931. In June 1932. A further exhibition with more than 200 works by German artists, including works by Käthe Kollwitz and George Grosz, was shown at the Chinese Y.M.C.A.

Word Count: 44

Shanghai LifeBookShanghaiShanghai Life was the first book published by the newly-founded Shanghai Cartoonist Club (March 7, 1942). The club held its first exhibition in June of the same year, at the Shanghai Art Gallery on Nanking Road (now Nanjing Dong Lu).

Word Count: 38